“Although they put the knife in, they rolled our heads, they burned our tongues. Although they forced our vaginas and took the fetuses out, we are not dead. With no skin on our bones, under seventy years of earth, we are still here.”

“Aunque el cuchillo metieron hasta dentro, rodaron nuestros cabezas, quemaron nuestras lenguas. Aunque forzaron nuestras vaginas y sacaron de dentro los fetos, no estamos muertas. Sin pellejo en los huesos, bajo setenta años de tierra, seguimos aquí.”

Subject to a discourse not exempt of metaphors and impressive aesthetic resources, the artist approaches activism with the certainty that his claims now have more power and scope than ever. To draw attention to the blindness of a society that has been dormant for too long is his laudable goal when devising and carrying out the Buried project on May 1, 2015 with the curatorship of Marisol Salanova, after more than a year of research, contacting associations and locating the protagonists.

A hundred people met under the rain on the esplanade at the Monumento a los Caídos in Pamplona where the remains of the Francoist generals Mola and Sanjurjo are buried and which, according to Azcona, "represents the capital and the hegemony of forgetfulness".

The project had the collaboration of the Association of relatives and disappeared of Navarra, as well as victims of all ages and generations, for example more than forty grandchildren of exiles in France who moved to the place specifically. The artist invited them to lie down to perform an emotional action with him.

The square is full of semi-hidden Francoist symbols that, according to the Navarre Symbols Law, should have been removed long ago. All the guests are related to a common pain, that of the loss or separation of a loved one in the past.

Their bodies were covered with soil one by one, the same soil that engulfed or repudiated corpses whose tragic history is rescued from the art world. All this is not trivial when facing the construction of historical memory.

The events that occurred during dictatorial and fascist periods have been silenced in different countries, Spain is not spared. Both during the Spanish Civil War and during the Franco era, a brutal number of people were murdered, most of whom lie in mass graves that are currently unidentified, they are disappeared, their family and friends have not been able to mourn for their deaths.

Their bodies were buried literally and metaphorically because by depriving them of identity, liturgy, mourning, they were condemned to oblivion.

Exiled, shot, slandered, disgraced, mutilated, mistreated, wounded, dead, buried.

Those human beings survive in full memory of their humanity through descendant relatives that the artist, in his work as a researcher, using social networks and internet resources, located and called for this performative ceremony that Buried consisted of, the greater macroperformance that has been made so far of these characteristics and with this activism value and the particular subversive sensitivity, political as energetic as well as agonizing that Azcona exudes, as someone who has really suffered and therefore is capable of empathizing and amplifying the voice of others who suffer, from respect .

Marisol Salanova, art critic y curator

Sujeto de un discurso no exento de metáforas e impactantes recursos estéticos, el artista se aproxima al activismo con la seguridad de que sus reivindicaciones tienen ahora más poder y alcance que nunca. Llamar la atención sobre la ceguera de una sociedad que ha permanecido adormecida demasiado tiempo es su loable objetivo al idear y llevar a cabo el proyecto Enterrados el 1 de mayo de 2015 con la curaduría de Marisol Salanova, tras más de un año de investigación, de contactar con asociaciones y localizar a los protagonistas. Un centenar de personas se citaron bajo la lluvia en la explanada del Monumento a los Caídos de Pamplona, en el que están enterrados los restos de los generales franquistas Mola y Sanjurjo y que, según Azcona, "representa la capital y la hegemonía de la desmemoria". El proyecto contó con la colaboración de la Asociación de familiares y desaparecidos de Navarra, así como damnificados de todas las edades y generaciones, por ejemplo más de cuarenta nietos de exiliados en Francia que se desplazaron al lugar ex profeso. El artista los invitó a tumbarse a realizar con él una emotiva acción.

La plaza está plagada de símbolos franquistas semiocultos que según la Ley de Símbolos de Navarra deberían haber sido retirados hace tiempo. Todos los invitados guardaban relación con un dolor común, el de la pérdida o separación de un ser querido en el pasado. Sus cuerpos fueron cubiertos uno a uno con tierra de la huerta de una de las víctimas del franquismo por el propio artista, la misma tierra que engulló o repudió unos cadáveres cuya trágica historia es rescatada desde el mundo del arte. Todo esto no es baladí de cara a la construcción de la memoria histórica.

Los sucesos acaecidos durante periodos dictatoriales y fascistas han sido acallados en diferentes países, España no se libra de ello. Tanto durante la Guerra Civil española como en la época franquista se asesinó a una cantidad brutal de personas la mayoría de las cuales yacen en fosas comunes sin identificar en la actualidad, son desaparecidos, sus familiares y amigos no han podido hacer el necesario duelo por sus muertes. Sus cuerpos fueron enterrados literal y metafóricamente porque al privarles de identidad, de liturgia, de duelo, se les condenó al olvido, algo que Azcona no tolera, algo contra lo que lucha y vence en su acción.

Exiliados, fusilados, calumniados, deshonrados, mutilados, maltratados, heridos, muertos, enterrados. Aquellos seres humanos sobreviven en el recuerdo plenos de su humanidad a través de parientes descendientes que el artista, en su labor de investigador, sirviéndose de las redes sociales y los recursos de internet, localiza y convoca para esta ceremonia performativa en que consiste Enterrados, la mayor macroperformance que se haya realizado hasta ahora de estas características, con el valor activista y la particular sensibilidad subversiva, política tan enérgica como a la par agónica que Azcona destila, como alguien que realmente ha sufrido y por ende es capaz de empatizar y amplificar la voz de otros que sufren, desde el respeto al límite.

Marisol Salanova, crítica de arte y comisaria

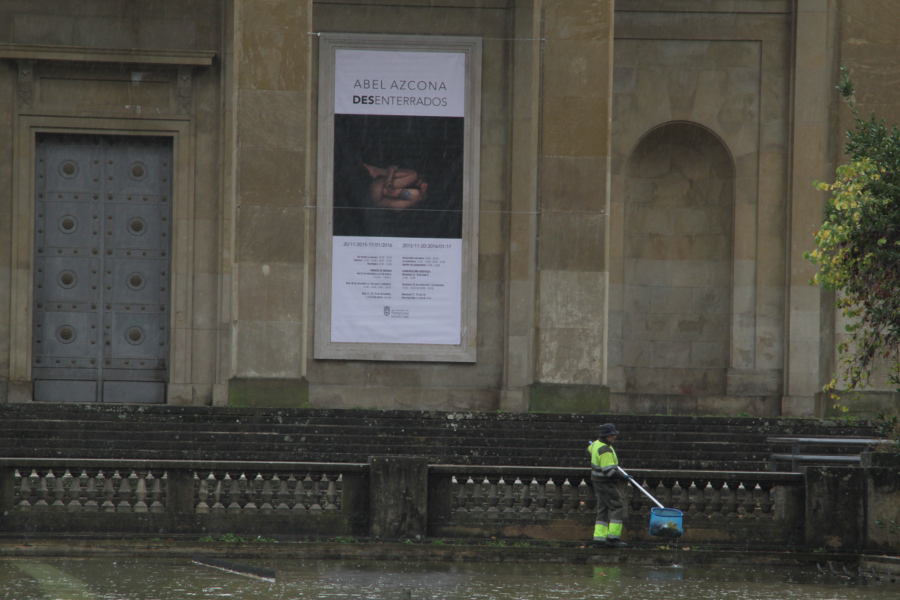

Buried is a procedural performative work created by artist Abel Azcona and developed on May 1, 2015 in the square of the Monumento a los Caídos in Pamplona. The work concludes when it is exhibited inside the Monumento a los Caídos from November 20, 2015 to January 17, 2016.

The piece is divided into two clearly differentiated stages. In the first one of them, through a collaborative performance or happening, dozens of children, grandchildren, nephews and other relatives of those shot and disappeared during the Civil War participated, staying for more than two hours lying on the ground while the artist buried them with earth from the garden of one of the family members of the shot. A live and bodily installation with great visual force in front of the Monument to the Fallen of Pamplona.

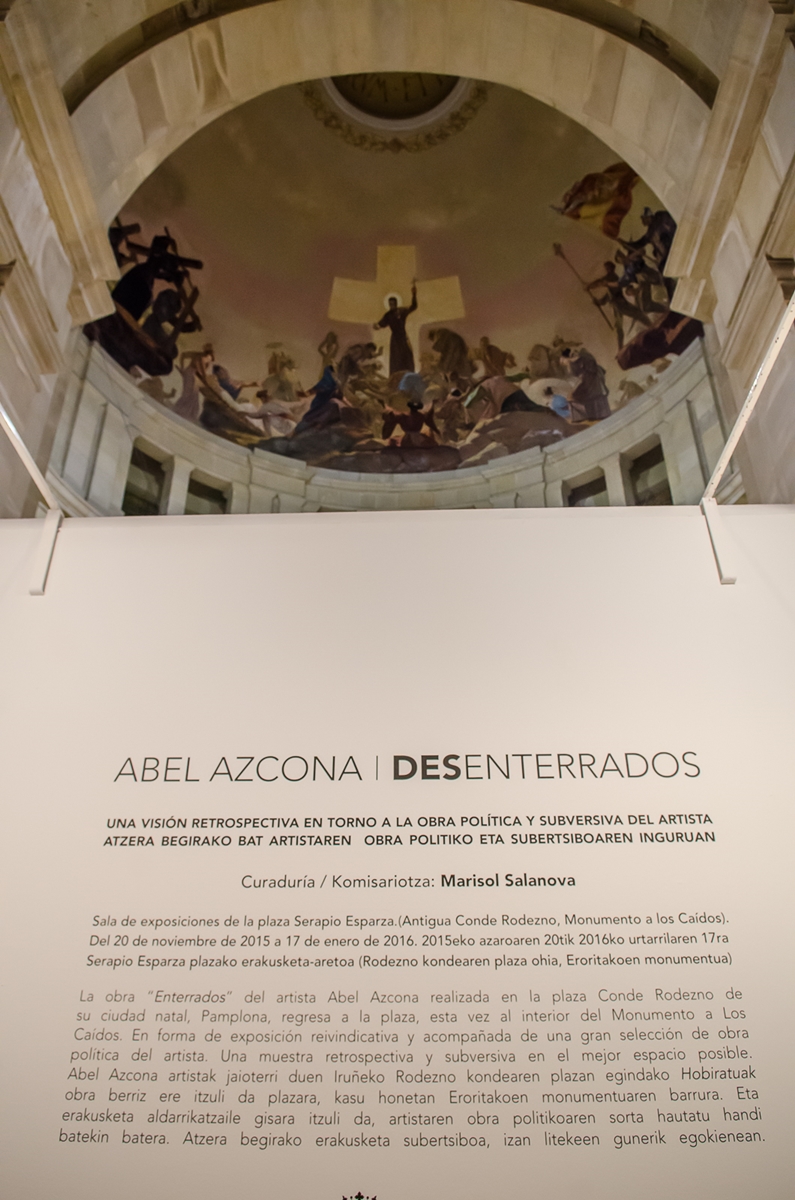

The second stage turns a performance into an exhibition; when entering the interior of the Monument, the work gained great strength by occupying the space where the names of the Francoist side used to be seen and the burial place of Mola or Sanjurjo, right-hand man of the dictator Francisco Franco. For the first time, the participants, children, grandchildren, relatives and friends of those shot and disappeared in the Spanish Civil War, entered the interior of the monument.

The initial performance called "Buried" thus became a large-scale display named "Unearthed", housing hundreds of photographs of the performance, a large installation with original land of the action, or small pieces of other Azcona performances, selected from curatorship for having a political and subversive intention. In total, more than five hundred works by Azcona in a great tribute show, carried out by his adoptive city inside the Monument, just in front of the esplanade where months ago he first performed the performance in vindication of repair and memory.

The Monumento a los Caídos of Pamplona, built in 1942 and inaugurated by the dictator Francisco Franco, used to display a retrospective sample of a wide selection of works by Abel Azcona, was designed with the purpose of remembering and paying tribute to the dead of the side revolted during the Spanish Civil War, whose names are engraved inside. Its rough appearance can be seen from a distance; In austere, monumental and durable stone forms, this building enhances the solidity of the regime, stands as a symbol of a fascist state in the middle of the urban environment, acting as a propaganda tool that dwarfs and favors the submission of the passerby.

_________________________

Enterrados es una obra performativa procesual creada por el artista Abel Azcona y desarrollada el 1 de Mayo de 2015 en la plaza del Monumento de los Caídos de Pamplona. La obra concluye al ser expuesta en el interior del Monumento a los Caídos del 20 de noviembre de 2015 al 17 de enero de 2016.

La pieza se divide en dos etapas claramente diferenciadas. En la primera de ellas, mediante una performance o happening colaborativo, decenas de hijos, nietos, sobrinos y otros familiares de fusilados y desaparecidos durante la Guerra Civil participaron, permaneciendo durante más de dos horas tendidos en el suelo mientras el artista los enterraba con tierra del huerto de uno de los familiares fusilados. Una instalación viva y corporal con gran fuerza visual frente al Monumento a los Caídos de Pamplona.

La segunda etapa convierte una performance en una muestra expositiva; al entrar en el interior del Monumento la obra cobra gran fuerza al ocupar el espacio donde antes lucían los nombres del bando franquista y el lugar de enterramiento de Mola o Sanjurjo, mano derecha del dictador Francisco Franco. Por primera vez los participantes, hijos, nietos, familiares y amigos de fusilados y desaparecidos en la Guerra Civil Española, entraban en el interior del monumento.

La performance inicial de nombre “Enterrados” se convertía así en una muestra de grandes dimensiones de nombre “Desenterrados”, al albergar cientos de fotografías de la performance, una gran instalación con tierra original de la acción, o pequeños retazos de otras performance de Azcona, seleccionadas desde curaduría por tener una intención política y subversiva. En total más de quinientas obras de Azcona en una gran muestra homenaje, realizada por su ciudad adoptiva en el interior del Monumento, justo en frente de la esplanada donde meses atrás realizó por primera vez la performance en reivindicación de la reparación y la memoria.

El Monumento a los Caídos de Pamplona, edificado en 1942 e inaugurado por el dictador Francisco Franco, utilizado para exponer una muestra retrospectiva de una amplia selección de obras de Abel Azcona, fue ideado con el propósito de recordar y rendir homenaje a los muertos del bando sublevado durante la Guerra Civil Española, cuyos nombres se encuentran grabados en su interior. Su aspecto tosco se aprecia desde la distancia; de formas austeras, monumental y de duradera piedra, este edificio enaltece la solidez del régimen, se alza como símbolo de un Estado fascista en medio del ámbito urbano, ejerciendo de herramienta propagandística que empequeñece y favorece la sumisión del viandante.

__________________________

With the special collaboration of / Con la colaboración especial de Affna36 Asociación de Familiares de Fusilados de Navarra - 1936

“The controversial performance exhibition by artist Abel Azcona in said room and the outer esplanade, “Amen” and “Buried/Unearthed” (Azcona, 2015-2016), which overflows the museum use of what is nothing but an attempt to hide its true condition, deranging the hypocrisy of a hidden but active presence of the Francoist memorial artifact. […] Contestant art has often been able to provide counter-leading voids of resistance: in Azcona’s work exhibited bodies reproduced and took the place of those buried performatively in the esplanade of the Monument to the Fallen, with land brought from fields and vineyards belonging to retaliated.

This is done, performatively occupying the esplanade of the monument where the civic-military and ecclesiastical authorities, the Carlist movements and the families of ex-combatants prostrated in 1961, the “whole” city, before the coffins of the Mola revolting generals and Sanjurjo with his provincial escort (of the fallen), that the place be reoccupied and re-sacralized with the truly “absent” dead: not by inability to appear, but by raptured right, present and recovered in other memories, overflowing what is lacking over what abounded. The device here overflows, not being able to assume or welcome, as in a plural cemetery, all those absent, also deactivating the vain and barbarous pretense of assimilation in the Valley of the Fallen of Cuelgamuros. In the same way, it reactivates the occluded product, providing, beyond the expired subjectivities, a zero place that refers to the underground. It is spoken and seen of what is silent and looks with the stupor of silence.”

“La polémica exposición performática del artista Abel Azcona en dicha sala y la explanada exterior, «Amén» y «Enterrados/ Desenterrados» (Azcona, 2015-2016), que rebosa el uso museístico de lo que no es sino un intento de ocultar su verdadera condición, desquiciando la hipocresía de una presencialidad oculta pero activa del artefacto memorial franquista. […] El arte contestatario ha podido proporcionar a menudo huecos contra-protagónicos de resistencia: en la obra de Azcona cuerpos exhibidos reproducían y tomaban el lugar los enterrados performativamente en la explanada del Monumento a los Caídos, con tierra traída de campos y viñas pertenecientes a represaliados. Esto hace, ocupando performativamente la explanada del monumento en la cual se postraron en 1961 las autoridades cívico-militares y ecle- siásticas, los movimientos carlistas y las familias de los excombatientes, la ciudad «entera», ante los féretros de los generales sublevados Mola y Sanjurjo con su escolta provincial (de los caídos), que se reocupe el lugar des- y re-sacralizándolo con los muertos verdaderamente «ausentes»: no por incapacidad de comparecencia, sino por derecho arrebatado, presentes y recuperados en otras memorias, desbordando lo que falta sobre lo que abundaba.

El dispositivo aquí se desborda, al no ser capaz de asumir o acoger, como en un cementerio plural, a todos los ausentes, desactivando igualmente la vana pretensión y bárbara de la asimilación en el Valle de los Caídos de Cuelgamuros. De igual modo, reactiva el producto ocluido, proporcionando, más allá de las subjetividades vencidas, un lugar cero que remite al subtierro. Se habla y se ve de lo que se calla y mira con el estupor del silencio.”

“The dead mausoleum in front of the living earth.

After a war that burns and stings even though we don’t want to see it, Franco’s memory still continues to crush us. So going to their memorials, standing in front of them and looking at them haughtily is also a gesture of rebellion that helps close that wound that still oozes in the stones. Because as much as they built great buildings to remind us of their victory, as much as they persecuted the republican people even into the graves of exile, here we are.

And in this country dignity continues to scratch that hot land of the lost graves, because we have not finished opening all the graves to the healing air.

Abel therefore wanted to confront the stone of the Monument to the Fallen of Pamplona, the only one in Spain, with the land of those gutters. He managed to make those direct children lie with their eyes open in front of the memory of their executioners, in an impressive contrast between the implacable victory and the solitude of the pit.

Abel has the ability to place with a sting his reflections in those dark spaces of memory and life in which few people actually dare to enter naked and alone as he does. So by burying us, bag by bag, Abel was uncovering Because there is no shadow, no stone, no building that can cover everything that happened.

Those one hundred bodies lying in that square that nobody walks through and nobody enjoys were the spokespersons for those thousands of disappeared people, in an exciting metaphor that their children and grandchildren starred in especially. And that is the plus of this action by Abel, that most of the people who fell on the ground, covered by the earth, were the direct victims. Neither actors, nor actresses, nor models ... the victims as protagonists.

The cold and damp earth, in front of the immensity of a mausoleum, the life that keeps the memory, in front of a huge and dead building. The perfect metaphor of the puppets that in the world have wanted to impose themselves in front of the simple people who fight for their own.

What Abel did, then, questions us in our contemporary reality. Because that building, which is located in the heart of a city especially punished by fascist repression, haunts us like a dark wasteland until we can throw it away. We know that to overlook is always the prelude to oblivion. And Abel proposed a universal and exportable reflection on the memory of the victors that imposes itself in the urban space in an immutable way as an enormous injury towards the victims.”

“El mausoleo muerto frente a la tierra viva.

Después de una guerra, que quema y escuece aunque no lo queramos ver, todavía la memoria franquista nos sigue aplastando. Así que acudir a sus memoriales, alzarnos frente a ellos y mirarlos con altivez es también un gesto de rebeldía que ayuda a cerrar esa herida que todavía supura en las piedras. Porque por mucho que construyeran grandes edificios para recordarnos su victoria, por mucho que persiguieran a la gente republicana hasta en las tumbas del exilio, aquí seguimos.

Y en este país la dignidad sigue arañando esa tierra caliente de las fosas perdidas, porque no terminamos de abrir todas las fosas al aire sanador.

Abel por eso quiso enfrentar la piedra del Monumento a los Caídos de Pamplona, único en toda España, con la tierra de esas cunetas. Él logró que aquellos hijos directos se tumbaran con sus ojos abiertos frente a la memoria de sus verdugos, en una contraposición impresionante entre la victoria implacable y la soledad de la fosa.

Abel tiene la capacidad de colocar con un aguijón sus reflexiones en aquellos espacios oscuros de la memoria y la vida en los que poca gente, en realidad, se atreve a entrar desnuda y sola como él lo hace. Así que enterrándonos, saco a saco, en realidad Abel destapaba. Porque no hay sombra, ni piedra, ni edificio que tape todo lo sucedido.

Esos cien cuerpos tumbados en aquella plaza que nadie recorre ni nadie disfruta, fueron los portavoces de esas miles de personas desaparecidas, en una metáfora emocionante que protagonizaron sobre todo sus hijos y sus nietos. Y ese es el plus de esta acción de Abel, que la mayoría de las personas que se tumbaron en el suelo, tapadas por la tierra, eran las víctimas directas. Ni actores, ni actrices, ni modelos... las víctimas como protagonistas de todo aquello.

La tierra fría y húmeda, frente a la inmensidad de un mausoleo, la vida que guarda la memoria, frente a un edificio enorme y muerto. La metáfora perfecta de los fantoches que en el mundo se han querido imponer frente a la gente sencilla que pelea por los suyos.

Esto que hizo Abel, entonces, nos cuestiona en nuestra realidad contemporánea. Porque ese edificio, que se ubica en pleno centro de una ciudad especialmente castigada por la represión fascista, nos persigue como un baldón oscuro hasta que lo podamos tirar. Sabemos que pasar por alto siempre es la antesala del olvido. Y Abel planteó una reflexión universal y exportable sobre la memoria de los vencedores que se impone en el espacio urbano de forma inmutable como un enorme agravio hacia las víctimas.”

Azcona's performance had national and international repercussions with several press covers dedicated to it, such as that of the Irish newspaper Irish Times.

_________________________

La performance de Azcona tuvo repercusión nacional e internacional con varias portadas de prensa escrita dedicadas a la misma como la del periódico irlandés Irish Times.

Plaza de Monumento a los Caídos de Pamplona, 1 de mayo de 2015.

Square of the Monumento a los Caídos in Pamplona, May 1st, 2015.

“I will try to tell the story of my family. I am a posthumous son of Arcadio Ibañez Sesma and Catalina San Juan Beruete. We were all born in Miranda de Arga, they told me about my father who was a man with many concerns at the time he had to live of poverty, injustice and social unrest since he took sides with the poor. In the first elections he was elected as a councilor, during the period in which he worked in the consistory he also did it with the concerned men of the town. They formed the Radical Socialist Republican Party, they had more than 200 members. These decided by vote that my father should be their president. With time the party was taking solidity in the shore and they decided to form candidacy for the Deputation. For Tudela Aquiles Cuadra, before going to the polls, he withdrew, for Azagra Félix Luri Amigot and for Miranda Arcadio Ibañez Sesma, the three were assassinated. In Navarra a right-wing republic emerged as the seven deputies left the traditional ranks. In the town there were two meeting places; In the Plaza el Casino, the wealthy gathered there and in the Mirandés Catholic Center simple people gathered, including the PRRS. They bought the press and read it aloud to inform their partners and regulars of the center of the news, since money was scarce and many had not attended school. I know all this because I met the party secretary, his name was Julio Elizalde Vergara, a wise and good man, I have a great memory of him, “son” he told me “they never forgave us to report what was happening outside the town”. He spent three years in the Fort of San Cristóbal, he told me everything that happened inside the fort, and it was very hard. When leaving, he did not dare to return to the town in a long time, I think this time was spent in Irún. He was empowered by my father to present himself as a Deputy. Time passed, my father married and when he finished his work at the town hall the marriage decided to try their luck in Zaragoza. They did well, they worked and my father studied law. Catalina, my mother, when she remembered this time, she said; The best years of my life were those that I spent in Zaragoza with your father. While in town, their respective families remained. The paternal grandfather, Julián, already a widower with three daughters María, Eulalia and Justa. The latter lived with her husband in the capital Maña. The children of Julián, my uncles, Victor arrested and imprisoned in the fort of San Cristóbal, we do not know where and how he was killed. Another of the sons, Ángel, at that time was a justice of the peace in the town. Joaquín, on the other hand, worked the land of his father, my grandfather. The two were detained and admitted to the town jail along with other colleagues from Miranda de Arga. They suffered ill-treatment, on the morning of August 3, 1936 they were pushed out and dragged along the slope, since they could not walk because of the blows received, so they reached the road and loaded them onto a truck. When they were in the truck a man from the town passed by, and looking at two of the group that were already upstairs, he told them; leave this and this one in the town as they are two of my best pawns. The truck started the journey to Dicastillo, where the rest were killed. I met the two men who were finally lowered from the truck, I was friends with them, but I never managed to tell them what happened. They were left speechless for life and they did not lack a voice, but fear gripped them. The women of the murdered men went with the food rings for the prisoners, among them my aunts, to see how their two brothers were doing. They fired them at their house saying “go to your house because there is no one here”, but the women are stubborn !!! they insisted on seeing how their relatives were and went to check it, and what they did not like a thing they saw. The blood-spattered walls of their loved ones had not yet been cleaned as a result of the blows they received. A few days later they called these women to the barracks, shaved their hair, made them take castor oil and walked them through the streets while making noise with pot lids to humiliate them. On my maternal family’s side, my aunts Saturnina, Inés and Julita and my uncles Agustín and Germán remained. The latter was also killed in Dicastillo, but his family circumstances were different, very different. Young, widowed and with five children who were orphaned. The daughters divided between the relatives and the boys in the Misericordia in Pamplona. A family forever broken. I have never come to understand this. Meaningless cruelty. On the other hand, my parents continued in Zaragoza and found out what had happened to their brothers, they had a very hard time not knowing what to do. In 1937 my father was arrested and put in the Torrero prison. My mother came to visit him two days later and was told that he had been released, “disappeared”. The thing is, my mother still didn’t know she was one month pregnant with me…My grandfather was alone with the daughters. Altogether they murdered my father and four other uncles, all of whom are missing. Was your idea to end the branch of the last name Ibañez ?. The shot went out the butt !!! In my marriage we only have boys, and they are five.”

“Intentaré relatar la historia de mi familia. Soy hijo póstumo de Arcadio Ibañez Sesma y Catalina San Juan Beruete. Todos nacimos en Miranda de Arga, me contaron de mi padre que fue un hombre con muchas inquietudes en el tiempo que le tocó vivir de pobreza injusticia y malestar social ya que tomó partido por los pobres. En las primeras elecciones fue elegido como concejal, durante el periodo en el que trabajó en el consistorio también lo hizo con los hombres preocupados del pueblo. Formaron el Partido Republicano Radical Socialista, llegaron a tener más de 200 afiliados. Estos decidieron por votación que fuera mi padre su presidente. Con el tiempo el partido fue tomando solidez en la ribera y decidieron formar candidatura para la Diputación. Por Tudela Aquiles Cuadra, antes de llegar a las votaciones se retiró, por Azagra Félix Luri Amigot y por Miranda Arcadio Ibañez Sesma, los tres fueron asesinados.En Navarra salió una república de derechas ya que los siete diputados salieron de las filas tradicionales. En el pueblo había dos lugares de encuentro; en la plaza el Casino, ahí se reunían los ricos y en el Centro Católico Mirandés se reunían la gente sencilla, entre ellos el PRRS. Estos compraban la prensa y la leían en voz alta para informar de la actualidad a sus socios y asiduos al centro, ya que escaseaba el dinero y muchos no habían ido a la escuela. Todo esto lo sé porque conocí al secretario del partido, se llamaba Julio Elizalde Vergara, un hombre sabio y bueno, tengo un gran recuerdo de él, hijo me decía nunca nos perdonaron que informáramos de lo que ocurría fuera del pueblo. El pasó tres años en el Fuerte de San Cristóbal, me contaba todo lo que ocurría dentro del fuerte, y fue muy duro. Al salir no se atrevió a volver al pueblo en mucho tiempo, creo que este tiempo lo pasó en Irún. Fue apoderado de mi padre para que se presentara como Diputado.Pasó el tiempo, mi padre se casó y al terminar su trabajo en el ayuntamiento el matrimonio decidió probar suerte en Zaragoza. Les fue bien, trabajaban y mi padre estudiada derecho. Catalina, mi madre, cuando recordaba este tiempo, decía; los mejores años de mi vida fueron los que pasé en Zaragoza al lado de tu padre. Mientras en el pueblo, quedaron sus respectivas familias. El abuelo paterno, Julián, ya viudo con tres hijas María, Eulalia y Justa. Esta última, vivía con su esposo en la capital maña. Los hijos de Julián, mis tíos, Victor detenido y preso en el fuerte de San Cristóbal, desconocemos donde y cómo fue asesinado. Otro de los hijos, Ángel, por ese tiempo era juez de paz en el pueblo. Joaquín, por otro lado, trabajaba la tierra de su padre, mi abuelo. Los dos fueron detenidos e ingresados en la cárcel del pueblo junto a otros compañeros de Miranda de Arga. Sufrieron malos tratos, en la mañana del 3 de agosto de 1936 los sacaron a empujones y arrastrándolos por la cuesta, ya que no podían andar por los golpes recibidos, así llegaron a la carretera y los subieron a un camión. Cuando estaban en el camión pasó un hombre del pueblo, y fijándose en dos del grupo que ya estaban arriba, les dijo; este y este otro dejarlos en el pueblo que son de mis mejores peones. El camión emprendió el viaje a Dicastillo, donde el resto fueron asesinados.Conocí a los dos hombres que fueron bajados finalmente del camión, tuve amistad con ellos, pero nunca logré que contaran lo sucedido. Los dejaron mudos para toda la vida y no les faltaba voz, pero les atenazaba el miedo. Las mujeres de los hombres asesinados fueron con los atillos de comida para los encarcelados, entre ellas mis tías, para ver como estaban sus dos hermanos. Las despidieron a su casa diciendo “ iros a vuestra casa que aquí ya no hay nadie”, pero buenas son las mujeres !!! se empeñaron en ver cómo estaban sus familiares y entraron a comprobarlo, y lo que vieron no les gustó nada. Aún no habían limpiado las paredes salpicadas de la sangre de sus allegados a raíz de los golpes recibidos.Unos días después llamaron a esta mujeres al cuartelillo, les raparon el pelo, les hicieron tomar aceite de ricino y las pasearon por las calles haciendo sonar las tapas de las cacerolas para humillarlas. Por parte de mi familia materna, quedaron mis tías Saturnina, Inés y Julita y mis tíos Agustín y Germán. Este último también fue asesinado en Dicastillo, pero sus circunstancias familiares eran otras, muy distintas. Joven, viudo y con cinco hijos que quedaron huérfanos. Las hijas repartidas entre los familiares y los chicos en la Misericordia de Pamplona. Una familia rota para siempre. Nunca he llegado a comprender esto. La crueldad sin sentido.Por otro lado, mis padres siguieron en Zaragoza y enterados de lo ocurrido con sus hermanos, lo pasaron muy mal sin saber qué hacer. En el año 1937 detienen a mi padre y lo ingresan en la cárcel de Torrero. Mi madre fue a visitarlo dos días más tarde y le dijeron que lo habían dejado libre, “desaparecido”. La cosa es que mi madre todavía no sabía que estaba embarazada de mi de un mes… Mi abuelo quedó solo con las hijas. En total asesinaron a mi padre y a cuatro tíos más, todos desaparecidos. ¿Su idea era terminar con la rama del apellido Ibañez?. ¡¡¡¡Les salió el tiro por la culata !!! En mi matrimonio sólo tenemos varones, y son cinco.”

“Javier Rocafort Apesteguía wrote several letters to his wife Dominica Lozano, from his confinement in Fort San Cristóbal, dated between the end of July 1936 and April 6, 1937. In this correspondence he tries to calm down his family and despite the harsh conditions in which the prisoners were, never wrote a complaint that could worry them, only affection and trust for his wife and their two small children, Mª Ángeles and Roberto, only 4 and 2 years old. Roberto: I think a lot about the boys … Don’t worry about me, because I am very well…. And since I have done nothing, they will do nothing to me, they took my statement and, naturally, they did not prosecute me because they have not found a sign of cause, therefore I am very quiet. On Thursday you left a little worried because you thought I was thinner, because I have to tell you that I am as always, very good, but since I did not know you were coming I did not shave and the beard disfigures a lot, I already said in the previous letter that you should not come because it is very cold and I feel sorry that you stop by to see me, because I will write to you every week. Do not have any pity for me because we are fine, what I want is for you to be strong and serene for things, knowing that you are well I no longer have any sorrows, Domi, take good care of yourself, I hope to find you well the same as you were before, because I would be disappointed if I found you deteriorated, although I already imagine that working as much as what you work cannot be good, Domi it seems to me that I will be as happy when we get together with our children as ever, well Believe me, everything you do for us, if I have health, I intend to more than compensate you, with nothing material you can be paid, but morally, as you already know I will...Now that you have more expenses, don’t worry about me, and you and the boys take care of yourselves as well as possible, because I already know that you will take away from yours so that the children and I will not lack anything, just as I will never be able to pay you for what you do for me even if I live a hundred years , the same will do the children when they are older, well I will let them know how much you sacrifice for them, because mother already told me that they are both very fat and very nice, because this is what reassures me the most, because this way I understand that their father’s lack is not known, and so I do not suffer for them, only for you. That is why I repeat in all the letters that I will have time if there is health, to compensate you more than anything and something else that is not paid with any money and I do not want to tell you more about this because I will tell you something, the day we get together forever, you tell María Angeles that I will bring her a doll and Roberto a horse. But the doll and the horse never came because they killed him the same day he wrote this letter.”

“Javier Rocafort Apesteguía escribió varias cartas a su mujer Dominica Lozano, desde su encierro en el fuerte San Cristóbal, fechadas entre finales de Julio de 1936 y el 6 de abril de 1937. En esta correspondencia trata de tranquilizar a su familia y a pesar de las duras condiciones en las que se encontraban los presos, jamás una queja que pudiera inquietarles, sólo cariño y confianza para su mujer y sus dos pequeños hijos, Mª Ángeles y Roberto de sólo 4 y 2 años de edad.Roberto:Me recuerdo mucho de los chicos … Por mí estar muy tranquilos, porque estoy muy bien….Y como yo nada he hecho, a mí nada me harán, me tomaron declaración y como es natural no me procesaron porque no han encontrado ni señal de causa, por lo tanto estoy muy tranquilo.El jueves te marchaste un poco preocupada porque te pareció que estaba yo más delgado, pues he de decirte que estoy como siempre, muy bien, sólo que como no sabía que ibas a venir no me afeité y la barba desfigura mucho, ya te decía en la carta anterior que no vendrías porque en primer lugar hace mucho frío y a mí me da pena que lo pases por verme, pues yo te escribiré todas las semanas. No tengas ninguna pena por mí que estamos bien, yo lo que quiero es que tú te encuentres fuerte y serena para las cosas, yo sabiendo que estáis bien ya no tengo penas.Domi, cuídate mucho, a ver si te encuentro bien lo mismo que estabas antes, pues me llevaría un disgusto si te encontrara desmejorada, aunque ya me figuro que trabajando tanto como lo que tú trabajas no se puede estar bien, Domi me parece que voy a ser tan feliz cuando nos juntemos con nuestros hijos como nunca, pues, créeme que todo lo que haces tú por nosotros, si tengo salud, pienso compensártelo con creces, con nada material se te puede pagar, sino moralmente, como ya sabes que lo haré…Tú ahora que tienes más gastos no te preocupes por mí, y tú y los chicos cuidaros todo lo mejor posible, pues ya sé que tú te quitarás de lo tuyo para que a los hijos y a mí no nos falte nada, así como yo no te podré pagar nunca lo que haces por mí aunque viva cien años, lo mismo harán los hijos cuando sean mayores, bien les haré reconocer lo mucho que tú te sacrificas por ellos, pues ya me dijo madre que están los dos muy gordos y muy majos, pues esto es lo que más me tranquiliza a mí, porque así comprendo que no se les conoce la falta de su padre, y así no sufro por ellos, sólo por ti.Por eso que te repito en todas las cartas que ya tendré tiempo si hay salud, para compensártelo todo con creces y algo más que no se paga con ningún dinero y no quiero hablarte más de esto porque ya te diré algo, el día que nos juntemos para siempreLe dices a Mª Angeles que le que le llevaré una muñeca y a Roberto un caballo.Pero la muñeca y el caballo no llegaron nunca porque lo mataron el mismo día que escribió esta carta.”

At the end of the work Azcona distributed the land among the spectators in the Plaza del Monumento a los Caídos in the city of Pamplona.

Al finalizar la obra Azcona repartió la tierra entre los espectadores en la Plaza del Monumento a los Caídos en la ciudad de Pamplona.

“Many have tried, but death and hatred have never corrupted her sweet smile. It still preserves intact the moving gaze of a child, although with that leftover temperance that looms after so many distressing experiences. Perhaps because she knows so well all the good and the bad that life can offer her. For 81 years, María Esther León Itoiz has kept all the images of her childhood, one by one, locked up, like the restless squirrel that collects hundreds of fruits and seeds in autumn so that winter does not catch her off guard. This way she will never forget who she is or where she comes from. She was born in Aoiz on January 25, 1931. She was the second daughter of Aurelio León Inda, the mayor of the town who was murdered on September 19, 1936 before turning 40. After his death, Aurelio left a young wife of 35 years, Juliana Itoiz Trece, and four small creatures: Andrea, who saw the war at 7 years old; Esther herself; María Jesús, who was 3 when Spain broke into two camps and died in 1940 “as the result of the sadness in which her mother was immersed”; and Alicia, who had been born three months before the military coup. Both Andrea, 84, and Alicia, 76, still live, although the former is quite ill. The national rifles did their job well when they shot to kill at the Tejería de Monreal. Aurelio and Juliana had married ten years before the war. And by the Church. All the girls were baptized, made their First Communion and went to mass on Sundays. The mayor of Aoiz considered himself a Republican, but “Catholic”. “He did not define himself as red” and did not like hobnobbing excessively with the nationalists, whom he described as “bourgeois”.

He was more comfortable “with the workers.” One of his best friends was a member of the Communist Party, which led them both to dialogue frequently on political issues, “but always with respect for each other’s ideas.” A year before the military coup “more or less”, he became first mayor of the municipality after the “resignation” of the winner of the elections, “a right-wing man”. He had come second. “In the town they wanted him and some rubbed their hands with his appointment, but he made it clear that he would not allow bullshit and that he would act against those who tried to become boastful for the simple fact of having a mayor they liked.” One day, he ordered several young people “who were messing with him” to be transferred to the barracks. And when they reproached him for his decision, he was firm: “I warned you,” he replied. The education of the little ones obsessed him so much that he himself prepared and corrected the children’s exams “and gave them to the teachers.” “He was a fighter and never charged for being mayor,” says Esther. Shortly before the war began, the parish priest, with whom Aurelio’s family had an “excellent friendship”, was replaced by a “right-wing” priest. At that time, Jaime lived in a house adjacent to the Civil Guard barracks. “He always got along well with the officers,” but the situation took a radical turn after the military coup. “One day, the guards asked my father if he could fix a broken sink for them. My uncle repaired it, but when he came out he ran into the new priest, who without biting his tongue released: “With these, you have to finish with these!” Many years later, my mother again met the priest who had been transferred and told him that if he had stayed in town, he would have never allowed my father and the other 22 Aoiz neighbors who were killed in Monreal to be taken away. “

Aurelio did not have a bad nose. At the back of the house, he left a temporary door in case he ever had to flee. “If things got bad, my father’s idea was to escape to the mountains and go to France. Everyone was aware of what could happen,” he stresses. The outbreak of the armed conflict was “lived very badly” at home: “It was horrible. My father would drive away from time to time and had organized his escape with some friends of Oroz Betelu because he knew they would come for him. “Betrayal, the weapon used by cowards, could have been key in his death. Or maybe it took a few weeks. Although now, Esther opts for the first hypothesis. The misfortune was consummated soon after, in early September, although Esther does not remember the exact date. That night, Aurelio was very annoyed, with “sciatica pain.”

The couple at that time shared the care of the young girl, so they rested in separate rooms: Juliana with Alicia, the newborn; the head of the family, with Andrea and Esther; and in a third room, located opposite theirs, María Jesús slept. “We left the doors open to communicate if someone needed something.” First they arrested Jaime, who did not hesitate to confront his captors. “One of them was the pharmacist from Leitza, Lizarza. I mention his last name because he behaved like a scoundrel. Jaime got up in his shorts and said that they were not going to take him anywhere. Suddenly, he punched Lizarza, who rolled down the stairs. What came after was terrible.” Then, several Falangists knocked on the León Itoiz door. As Aurelio could not get out of bed, Esther’s mother went to the window. She asked them what they wanted, and the others, who had arrived in a van, replied that they were going to “take” her husband. Desperate Juliana reproached them for not being able to move, but they cared little. When the criminals tainted their home, Aurelio asked them for something in return: not to disturb their daughters. “I have a recorded image that I will never forget. While my father was dressing, I saw Lizarza’s shadow reflected on a wall with a pistol in his hand. Although my father wanted to kiss us, they didn’t let him. And they put him in the van, where my uncle was. Then they went to find more neighbors.” The first mayor of Aoiz and Jaime were imprisoned in the Piarists of Pamplona, so the following day Juliana traveled by train to the Navarrese capital to bring them clothes and food, since “they had left with nothing”. Like many others, she could never see them. On September 19, both were shot in the Tejería de Monreal. In total, “23 Aoiz residents and a group from Tafalla died.”

Soon the news of the murders arrived. “We found out because some of the people went to Lumbier to shave the women’s hair and give them castor oil so that they could make feces in the streets and vice versa. They were talking to each other ... My mother was not subjected to such a humiliation because someone must have said that they had bothered her enough. When she found out what had happened, she became extremely nervous. And she was very, very sick. They believed that she would pass away. I spent whole days in bed and my aunt Eufrasia, my mother’s sister, asked her not to give up, because they could not face the future if she died. Shattered, she replied that they did what they wanted to. The daughters were distributed to us with several relatives from the town, who helped us.” Juliana’s daughters still had to face another humiliation: singing the ‘Cara al Sol’every day when they came “forced” to eat at the Social Aid. Before and after gobbling up the ranch. In addition, Aurelio’s business was lost, but at least they kept the house and the car, where the girls sneaked around whenever their mother was doing his chores. Shortly after, the ghosts of the past crossed the widow’s path for the first time. “A neighbor denounced her because, according to her, she was not going to mass.

And one day, while in Pamplona, my mother met her friend’s husband and told him what she thought. She was ever silent. ‘Well done! To wait for you to leave so they could take Aurelio. Or did you ask to be transferred so that they could catch everyone?` She reproached him. She was convinced that he had influenced the deaths of my father and my uncle and he did not respond.” Before 1940, that man’s wife lost her life.”

“ Muchos lo han intentado, pero la muerte y el odio jamás han corrompido su dulce sonrisa. Todavía conserva intacta la conmovedora mirada de una cría, aunque con ese poso de templanza que se vislumbra tras tantas experiencias angustiosas. Tal vez porque conoce de sobra todo lo bueno y lo malo que puede ofrecerle la vida. A lo largo de 81 años, María Esther León Itoiz ha guardado bajo llave, una a una, todas las imágenes de su infancia, como la inquieta ardilla que recoge cientos de frutos y semillas en otoño para que el invierno no le coja desprevenida. Así jamás olvidará quién es ni de dónde procede.Nació en Aoiz el 25 de enero de 1931. Fue la segunda de las hijas de Aurelio León Inda, alcalde de la localidad al que asesinaron el 19 de septiembre de 1936 sin haber cumplido los 40. Tras su fallecimiento, Aurelio dejó una joven esposa de 35 años, Juliana Itoiz Trece, y cuatro pequeñas criaturas: Andrea, que vio la guerra con 7 años; la propia Esther; María Jesús, que tenía 3 cuando España se quebró en dos bandos y falleció en 1940 “fruto de la tristeza en la que se vio inmersa su madre”; y Alicia, que había nacido tres meses antes del golpe militar. Tanto Andrea, de 84 años, como Alicia, de 76, aún viven, aunque la primera se encuentra bastante enferma. Los fusiles nacionales hicieron bien su trabajo cuando dispararon a matar en la Tejería de Monreal.Aurelio y Juliana se habían casado diez años antes de la guerra. Y por la Iglesia. Todas las niñas fueron bautizadas, hicieron la Primera Comunión e iban a misa los domingos. El alcalde de Aoiz se consideraba republicano, pero “católico”. “No se definía como rojo” y no le gustaba codearse en exceso con los nacionalistas, a los que calificaba de “burgueses”. Él se encontraba más cómodo “con los obreros”. Uno de sus mejores amigos era miembro del Partido Comunista, lo que propició que ambos dialogaran a menudo sobre temas políticos, “pero siempre con respeto hacia las ideas del otro”.Un año antes del golpe militar “más o menos”, se convirtió en primer edil del municipio tras la “dimisión” del ganador de las elecciones, “un hombre de derechas”. Él había quedado en segundo lugar. “En el pueblo lo querían y algunos se frotaron las manos con su nombramiento, pero él dejó bien claro que no permitiría follones y que actuaría contra quienes trataran de hacerse los fanfarrones por el simple hecho de tener un alcalde que les gustaba”. Un día, ordenó trasladar al cuartelillo a varios jóvenes “que la estaban liando”. Y cuando éstos le recriminaron su decisión, se mostró firme: “Os lo advertí”, les respondió. La educación de los más pequeños le obsesionaba tanto que él mismo preparaba y corregía los exámenes de los niños “y se los daba a las maestras”. “Era un luchador y jamás cobró por ser alcalde”, asegura Esther.Poco antes de que comenzara la guerra, el párroco, con el que la familia de Aurelio mantenía una “excelente amistad”, fue sustituido por un sacerdote “de derechas”. En aquel momento, Jaime vivía en una casa colindante al cuartel de la Guardia Civil. “Siempre se llevó bien con los agentes”, pero la situación dio un giro radical a partir del golpe militar.“Un día, los guardias le preguntaron a mi padre si podía arreglarles una fregadera que estaba rota. Mi tío la reparó, pero al salir se topó con el nuevo cura, que sin morderse la lengua soltó: ‘¡Con éstos, con éstos hay que acabar!’. Muchos años después, mi madre volvió a encontrarse con el sacerdote al que habían trasladado y le dijo que si él se hubiera quedado en el pueblo, jamás habría permitido que se llevaran a mi padre y a los otros 22 vecinos de Aoiz que fueron asesinados en Monreal”.

Aurelio no andaba mal de olfato. En la parte trasera de la casa, dejó una puerta provisional por si algún día se veía obligado a huir. “Si las cosas se ponían feas, la idea de mi padre era escaparse al monte y pasar a Francia. Todo el mundo estaba al tanto de lo que podía ocurrir”, subraya.El estallido del conflicto armado “se vivió muy mal” en casa: “Fue horrible. Mi padre se marchaba de vez en cuando con el coche y había organizado su fuga con unos amigos de Oroz Betelu porque sabía que irían a por él”. La traición, el arma arrojadiza que emplean los cobardes, pudo ser clave en su muerte. O tal vez la demoró unas semanas. Aunque ahora, Esther se decanta por la primera hipótesis.La desgracia se consumó poco después, a principios de septiembre, aunque Esther no recuerda la fecha exacta. Aquella noche, Aurelio estaba muy fastidiado, con “dolores de ciática”. El matrimonio se repartía en aquella época el cuidado de las crías, de modo que descansaban en habitaciones separadas: Juliana con Alicia, la recién nacida; el cabeza de familia, con Andrea y Esther; y en un tercer cuarto, situado frente al de éstas, dormía María Jesús. “Dejábamos las puertas abiertas para comunicarnos si alguien necesitaba algo”.Primero detuvieron a Jaime, que no dudó en enfrentarse a sus captores. “Uno de ellos era el farmacéutico de Leitza, un tal Lizarza. Te menciono su apellido porque se portó como un canalla. Jaime se levantó en calzoncillos y dijo que a él no le iban a llevar a ninguna parte. De repente, propinó un puñetazo a Lizarza, que rodó escaleras abajo. Así que se organizó una terrible”.Acto seguido, varios falangistas llamaron a la puerta de los León Itoiz. Como Aurelio no podía levantarse de la cama, la madre de Esther salió a la ventana. Les preguntó qué querían y los otros, que habían llegado en una camioneta, le respondieron que iban “a coger” a su marido. Juliana, desesperada, les recriminó que no podía moverse, pero poco les importó.Cuando los criminales mancillaron su hogar, Aurelio les solicitó algo a cambio: que no molestaran a sus hijas. “Tengo una imagen grabada que jamás olvidaré. Mientras mi padre se vestía, vi la sombra de Lizarza reflejada en una pared con una pistola en la mano. Aunque mi padre quería darnos un beso, no le dejaron. Y lo metieron en la furgoneta, donde estaba mi tío. Luego se dirigieron a por más vecinos”.El primer edil de Aoiz y Jaime fueron encarcelados en los Escolapios de Pamplona, de modo que al día siguiente Juliana viajó en tren hasta la capital navarra para llevarles ropa y comida, ya que “habían salido sin nada”. Como muchos otros, jamás pudo verlos. El 19 de septiembre, ambos fueron fusilados en la Tejería de Monreal. En total, “murieron 23 vecinos de Aoiz y un grupo de Tafalla”.Pronto llegó la noticia de los asesinatos. “Nos enteramos porque algunos del pueblo iban a Lumbier a rapar el pelo a las mujeres y a darles aceite de ricino para que se hicieran las heces por las calles y al revés. Entre ellos hablaban… A mi madre no le sometieron a semejante vejación porque alguien debió de decir que ya le habían fastidiado bastante. Cuando supo lo que había sucedido, se puso fatal de los nervios. Y estuvo muy, pero que muy enferma. Creían que fallecería. Pasaba días enteros en la cama y mi tía Eufrasia, hermana de mi madre, le pedía que no se rindiera, porque no podrían afrontar el futuro si ella moría. Ella, destrozada, le respondía que hicieran lo que quisieran. A las hijas nos repartieron con varios parientes del pueblo, que nos echaron una mano”.

Las hijas de Juliana aún tuvieron que enfrentarse a otra humillación: cantar el ‘Cara al sol’ cada día cuando acudían “obligadas” a comer al Auxilio Social. Antes y después de engullir el rancho. Además, el negocio de Aurelio se perdió, pero al menos conservaron la casa y el coche, donde las niñas jugaban a hurtadillas siempre que su madre estaba realizando sus labores. Poco después, los fantasmas del pasado se cruzaron por primera vez en el camino de la viuda.“Una vecina la denunció porque, según ella, no iba a misa. Y un día, estando en Pamplona, mi madre se encontró con el esposo de su amiga y le puso fino. Jamás se callaba nada. ‘¡Qué bien lo has hecho! Esperar a que te fueras para que se llevaran a Aurelio. ¿O pediste tú que te trasladaran para que pudieran coger a todos?’, le reprochó. Ella estaba convencida de que había influido en las muertes de mi padre y mi tío y él ni respondió”. Antes de 1940, la esposa de aquel hombre perdió la vida.”

Monumento a los Caídos in Pamplona with the exhibition Unearthed: A retrospective vision of the political and subversive work by Abel Azcona. Monumento a los Caídos de Pamplona con la exposición Desenterrados: Una visión retrospectiva de la obra política y subversiva del artista Abel Azcona.

The exhibition Unearthed by artist Abel Azcona inside the Monumento a los Caídos of Pamplona, from November 20, 2015 to January 17, 2016 with the curatorship of Marisol Salanova, arises from the performance project carried out months before, in May 2015, in the Plaza de Conde Rodezno in his hometown. Product of more than a year of research and production processes, during the performance titled Buried in May the artist gathered a series of relatives of victims of Francoism and poured soil from the garden of one of the victims on their bodies lying in the square as a claiming tribute to historical memory.

A place that worships true murderers and is riddled with symbols of the Spanish dictatorship is metaphorically outraged or rather rescued by a political and subversive work that involves a change of course in search of justice that for decades and decades relatives and friends of people who lost their lives atrociously at the hands of the Francoist side have been waiting for, whose bones have not even been found, disappeared, who were probably shot and buried in mass graves, preventing the mourning of their loved ones.

Abel Azcona has worked on his own suffering and that of others with a capacity for empathy and skill in his actions worthy of the international recognition he holds. Interdisciplinary artist who has shown his work in public and private centers in countries such as Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Denmark, England, Germany, Greece, Mexico, Venezuela, Peru, Argentina, the United States, Colombia, China, the Philippines and Japan. He has curated performance projects such as the International Performance Art Festivals of Pamplona, Bogotá and New York and various gallery and museum exhibitions such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Bogotá, also teaching workshops at prestigious institutions as a teacher.

He has been arrested on numerous occasions for his transgressive behavior in repressive environments, especially in his land, Navarra, where he is finally appreciated for his career, reflected in this retrospective vision with the title Unearthed accompanied by a large selection of the artist's political work. The City Council of Pamplona, in the midst of political change, is launching this exhibition project that opens the door to a new stage of exhibitions in this space, the Monumento a Los Caídos, in the same square whose esplanade hosted Buried.

What we find in him during Azcona's exhibition are like action maps; his performances gutted in a metaphorical sense when able to contemplate and understand their process, invite the viewer to read them and take part with words, body and letters. It is mounted so that the viewer can see the process in a clean, poetic way, to play with the idea of process being an evolution of the piece, that is, it is an installation montage, the public becomes part of that performance that has already happened and whose documentation is in dialogue with previous pieces of a political nature also.

Everything exposed in space with such a strong, hard load, which amounts to being an old desacralized church. Rare atmosphere of texts, photographs and installation, a very contemporary montage, from the absolute respect, for which projects with a political purpose are unearthed and have in common having facilitated the empowerment of other people thanks to the artist and his empathy towards them.

With careful attention to detail and conceptually very powerful, Azcona's work explores and pays great attention to the plastic result as it relates to media such as photography, video art, artistic installation and sculpture. His artistic work, in which he always ends up involving his body, and his own creative process serve as a tool for self-knowledge. He considers art as a great way to compensate for his internal tear, to sublimate an obsession and to extend catharsis to others who need it. In this and other projects, practically all of them, the artist does not seek to be the protagonist but to give voice to those who suffer.

Combining his life experience with that of other people, he identifies pain and its causes and passes it through the filter of art, taking corporality to the limit, risking and endangering himself with an activist zeal that is both introspective and expansive.

Francisco Franco was a Spanish military man and dictator who, along with other high-ranking officials of the military leadership, promoted the coup in July 1936 against the democratic government of the Second Republic, causing the Spanish Civil War. At that time, everyone who opposed his ideology was locked up, tortured and / or shot. General Mola, who was the military governor of Pamplona and head of the so-called Northern region, was involved in the coup and his cruelty was felt in the region.

His tomb and that of the Generalissimo are located in the Monument to the Fallen, on these Azcona places his pieces of a subversive character, generating controversy in a deep and honest reflection on our past, shedding light on the concept of identity, an intimate work and empowerment with liturgical resources and at the same time a very provocative aspect.

Marisol Salanova

La exposición Desenterrados del artista Abel Azcona en el interior del Monumento a Los Caídos de Pamplona, del 20 de noviembre de 2015 al 17 de enero de 2016 con la curaduría de Marisol Salanova, surge a partir del proyecto performativo que lleva a cabo meses antes, en mayo de 2015, en la plaza de Conde Rodezno de su ciudad natal. Producto de más de un año de investigación y procesos de producción, durante la performance titulada Enterrados en mayo el artista congregó a una serie de familiares de víctimas del franquismo y vertió tierra procedente de la huerta de una de las víctimas sobre sus cuerpos tumbados en la plaza a modo de homenaje reivindicativo sobre la memoria histórica.

Un lugar que rinde culto a auténticos asesinos y está plagado de símbolos todavía de la dictadura española es metafóricamente ultrajado o más bien rescatado por una obra política y subversiva que supone un cambio de rumbo en busca de la justicia que durante décadas y décadas llevan esperando familiares y amigos de personas que perdieron la vida de forma atroz a manos del bando franquista cuyos huesos ni siquiera han sido encontrados, desaparecidos que probablemente fueron fusilados y enterrados en fosas comunes impidiendo el duelo de sus seres queridos.

Abel Azcona ha trabajado en torno al sufrimiento propio y ajeno con una capacidad de empatía y destreza en sus acciones digna del reconocimiento internacional que ostenta. Artista interdisciplinar que ha mostrado su obra en centros públicos y privados de países como España, Portugal, Francia, Italia, Dinamarca, Inglaterra, Alemania, Grecia, México, Venezuela, Perú, Argentina, Estados Unidos, Colombia, China, Filipinas y Japón. Ha comisariado proyectos de performance como los Festivales Internaciones de Performance Art de Pamplona, Bogotá y Nueva York y diversas exposiciones en galería y museos como el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Bogotá, también impartiendo workshops en prestigiosas instituciones como docente.

Ha sido detenido en numerosas ocasiones por su conducta transgresora en ambientes de represión, especialmente en su tierra, Navarra, donde por fin es apreciado por su trayectoria, reflejada en esta visión retrospectiva con el título Desenterrados acompañada de una gran selección de obra política del artista. El Ayuntamiento de Pamplona, en pleno contexto de cambio político, pone en marcha este proyecto expositivo que abre la puerta a una nueva etapa de muestras en este espacio, el Monumento a Los Caídos, en la misma plaza cuya explanada alojó Enterrados.

Lo que encontramos en él durante la exposición de Azcona son como mapas de acción; sus performance destripadas en sentido metafórico al poder contemplar y entender su proceso, invitan al espectador a leerlas y formar parte con palabras, cuerpo y letras. Está montada de manera que el espectador pueda ver el proceso de forma limpia, poética, para jugar con que el proceso sea una evolución de la pieza, es decir, se trata de un montaje instalativo, el público se vuelve parte de esa performace que ya ha sucedido y cuya documentación encuentra en diálogo con piezas anteriores también de corte político. Todo expuesto en espacio con una carga tan fuerte, duro, lo que viene a ser una antigua iglesia desacralizada. Ambiente enrarecido de textos, fotografías e instalación, un montaje muy contemporáneo, desde el más absoluto respeto, para el cual se desentierran proyectos que tienen un fin político y que tienen en común el haber facilitado el empoderamiento de otras personas gracias al artista y su empatía con ellas.

De estética cuidada al detalle y conceptualmente muy potente, el trabajo de Azcona explora y presta gran atención al resultado plástico por lo que está relacionado con medios como la fotografía, el videoarte, la instalación artística y la escultura. Su obra artística, en la que siempre acaba involucrando su cuerpo, y su propio proceso creativo le sirven como herramienta de autoconocimiento. Considera el arte como un gran medio de compensar su desgarramiento interior, de sublimar una obsesión y extender la catarsis a otras personas que lo necesiten. En este y otros proyectos, prácticamente todos, el artista no busca ser el protagonista si no dar voz a quienes sufren. Conjugando su experiencia vital con la de otras personas identifica el dolor y sus causas y lo pasa por el filtro del arte llevando la corporalidad al límite, arriesgando y poniéndose en peligro con una afán activista a la vez introspectivo y expansivo.

Francisco Franco fue un militar y dictador español que impulsó, junto a otros altos cargos de la cúpula militar, el golpe de Estado de julio de 1936 contra el gobierno democrático de la Segunda República, provocando la Guerra Civil Española. En aquella época todo el que se oponía a su ideología era encerrado, torturado y/o fusilado. El General Mola, que fuera gobernador militar de Pamplona y jefe de la llamada entonces región del Norte, estuvo implicado en el golpe de estado y su crueldad se hizo notar en la región. Su tumba y la del Generalísimo se hallan ubicadas en el Monumento a los Caídos, sobre éstas Azcona situa sus piezas de caracter subversivo, generando controversia en un reflexión profunda y honesta sobre nuestro pasado, arrojando luz sobre concepto de identidad, un trabajo íntimo y de empoderamiento con recursos litúrgicos y a la vez una parte muy provocativa.

Marisol Salanova

Buried - Unearthed is a performative and expositive work conceived as a reflection and exploration on memory and reparation. Part of the work currently belongs to the Contemporary Art Collection of the Town Hall of Pamplona. Photography: Santi Vaquero and communication of corresponding museums.

Enterrados - Desenterrados es una obra performativa y expositiva nacida como reflexión y exploración de la memoria y la reparación. Parte de la obra pertenece en la actualidad a la Colección de Arte Contemporáneo del Ayuntamiento de Pamplona. Fotografía: Santi Vaquero y comunicación de museos correspondientes.

Buried in expositive format in the Centro Juan De Salazar in Asunción in Paraguay

Enterrados en formato expositivo en el Centro Juan De Salazar de Asunción en Paraguay.

Enterrados en exposición en el Centro Cultural España de Tegucigalpa en Honduras.

Enterrados en formato expositivo en el Centro Juan De Salazar de Asunción en Paraguay.

In 2017 and 2018 the work Buried traveled and was exhibited in the Amadis Hall of Injuve and in the Centro de Artes de la Fábrica de las Artes Roca Umbert in Granollers-Barcelona. And on a Latin American tour at the Juan de Salazar Center in Asunción in Paraguay, at the Spain Cultural Center in Tegucigalpa in Honduras, at the Spain Cultural Center in Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic and at the Spain Cultural Center in Montevideo in Uruguay. Curatorship: Gerardo Silva.

________________________

En 2017 y 2018 la obra Enterrados viaja y se expone en la Sala Amadis de Injuve y en el Centro de Artes de la Fábrica de las Artes Roca Umbert de Granollers-Barcelona. Y en una gira latinoamericana en el Centro Juan de Salazar de Asunción en Paraguay. En el Centro Cultural España de Tegucigalpa en Honduras, en el Centro Cultural España de Santo Domingo en República Dominicana y en el Centro Cultural España de Montevideo en Uruguay. Comisariado: Gerardo Silva.

Buried in exhibition in the Instituto de la Juventud INJUVE in Madrid, Spain. / Enterrados en exposición en el Instituto de la Juventud INJUVE en Madrid, España.

Buried exhibited in the Spain Cultural Centre in Tegucigalpa in Honduras.

Buried exhibited in the Espacio de Artes de la Fábrica de las Artes Roca Umbert.

Buried exhibited in the Spain Cultural Centre in Santo Domingo, Dominicana.

Buried in expositive format in the Centro Juan De Salazar in Asunción in Paraguay