At the foot of the road that connects Sagunto with Burgos, just ten kilometers away from Teruel, are the so-called Pozos de Caudé. The wells were, since the first days of August 1936 until December 1937, the sad scene of numerous extrajudicial executions organized in a systematic way by the July 18 rebels of and their followers. Although the figure is still imprecise, the Wells are estimated to house the bodies of more than 1,000 “desafectos” civilians.

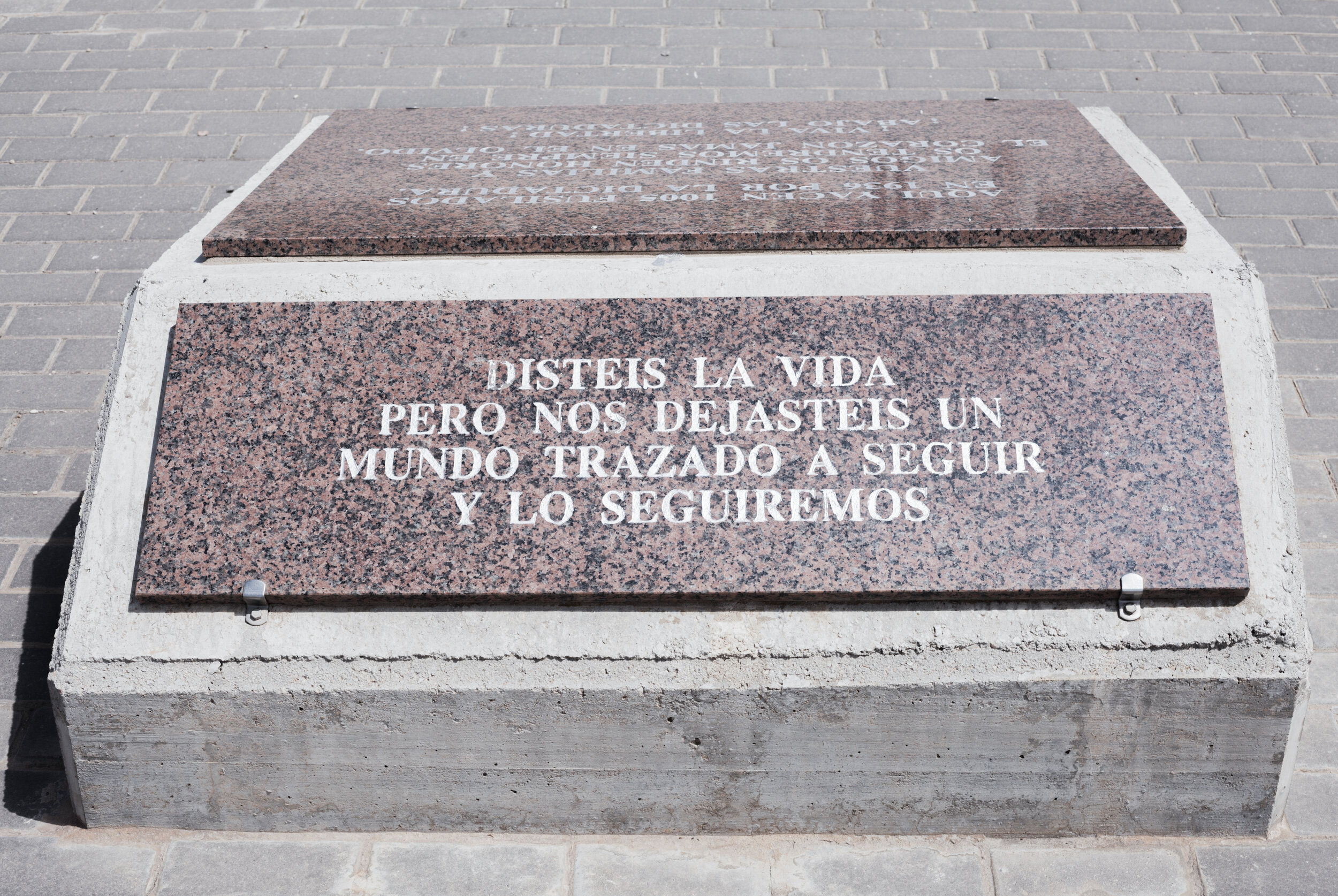

The space currently known as "Pozos de Caude" was originally occupied by an inn, now disappeared, with an artesian well 87 meters deep, into which numerous shot bodies were dumped plus another mass grave about 500 meters away, where there must have been another well. A third grave about 1,000 meters away, where the remains of a farmhouse or an inn were used as a wall. In addition, the remains of seven other people when working on the opening of a ditch for gas pipelines and a fifth pit towards the San Blas ravine that was not known so far have been found. The skulls appear with the coup de grace hole that the executed ones received and that made it possible to count up to 1,005 shots when the executions took place, between the beginning of August 1936 and December 1937. In this same place the relatives and friends of the murdered, as well as solidarity and anti-fascist people, began to build in late 1977 the "place of memory" that we now know and in which a monolith was installed and memorial plaques were placed.. Every year a tribute is organized and attended by hundreds of people.

___________________________

Al pie de la carretera que une Sagunto con Burgos, a apenas diez kilómetros de Teruel, se encuentran los denominados Pozos de Caudé. Los pozos fueron, desde los primeros días de agosto de 1936 hasta diciembre de 1937, el triste escenario de numerosas ejecuciones extrajudiciales organizadas de una forma sistemática por los sublevados del 18 de julio y sus seguidores. Aunque la cifra sigue siendo aún imprecisa, se estima que los Pozos albergan los cuerpos de más de 1000 civiles “desafectos”.

El espacio conocido actualmente como "Pozos de Caude" estaba ocupado originariamente por una venta, hoy desaparecida, con un pozo artesiano de 87 metros de profundidad, al que se arrojaron numerosos cadáveres de fusilados y al que hay que sumar otra fosa común a unos 500 metros, donde debió haber otro pozo. Una tercera fosa a unos 1.000 metros, donde los restos de una masía o venta fueron utilizados como paredón. Además se han encontrado restos de otras siete personas cuando se trabajaba en la apertura de una zanja para las canalizaciones de gas y una quinta fosa hacia el barranco de San Blas que no era conocida hasta el momento. Los cráneos aparecen con el agujero del tiro de gracia que recibieron los fusilados y que permitieron contar hasta 1.005 disparos cuando se produjeron las ejecuciones, entre principios de agosto de 1936 y diciembre de 1937. En este mismo lugar los familiares y amigos de los asesinados, asi como personas solidarias y de sensibilidad antifascista comenzaron a construir a finales de 1977 el "lugar de memoria" que ahora conocemos y en el que se instaló un monolito y también se pusieron diferentes placas recordatorias. En este lugar se celebra todos los años un homenaje al que acuden cientos de personas.

Desafectos is a procedural performative work created by artist Abel Azcona, inaugurated and completed in the Pozos de Caudé. During 2016, Azcona was invited by the organization of relatives of the disappeared and shot in the Pozos de Caudé to carry out another action about historical memory. For hours, the relatives and Azcona built a wall similar to the walls that the executed themselves had to build in the wells as part of the forced labor carried out at that time. After hours of physical effort by the relatives and the creator, they all remained for an hour in a firing squad position on the wall built on their own built.

Desafectos is a metaphorical construction carried out by relatives, children, great-grandchildren and friends of the disappeared in the Pozos de Caudé. Forced labor was a common punishment in times of war and post-war, sometimes calling prisoners, retaliated against and deprived of their liberties, “desafectos”. The ideological and territorial division of the Spanish state after the military uprising of 1936 had one of its greatest expressions in the punishments and purges of those considered "responsible for any fact that due to its circumstances and consequences should be considered as harmful to the interests of the people and the Government» in the rebel area, who were officially called «disaffected by the regime». Sympathizers of unions, leftist parties or the Popular Front received this name when they were grouped as Workers Battalions, subjugated and destined for forced labor. These Battalions, formed with the surplus of prisoners from warehouses and concentration camps, constituted during the Spanish Civil War and Post-War "the largest system of captive labor in contemporary Spain" and covered the need for infrastructure and civil constructions. Many of those shot in the Wells had been forced to work building for the regime in the area to later be grouped and shot on the esplanade that today remembers their deaths.

Artist Abel Azcona travelled invited by the Association Pozos de Caudé. Design and carry out a performance action with friends, grandchildren and other family members. For hours, together they built, at the place where the bodies of the 1005 shot men were dumped, a stone and concrete wall. More than fifty people collaborated in the construction of the installation and at the end they remained an hour in front of the wall in memory, catharsis and empowerment. An intimate and personal process, where all of them carried out an exercise of justice, memory and reparation.

Desafectos es una obra performativa procesual creada por el artista Abel Azcona, inaugurada y finalizada en los Pozos de Caudé. Durante el año 2016, Azcona es invitado a realizar otra acción entorno a la memoria histórica, esta vez por la organización de familiares de desaparecidos y fusilados en los Pozos de Caudé. Durante horas, los familiares y Azcona construyeron un muro símil a los muros que los propios fusilados debían construir en los pozos dentro de los trabajos forzados llevados a cabo en aquella época. Después de horas de esfuerzo físico por parte de los familiares y el creador, todos permanecieron durante una hora en posición de fusilamiento en su propio muro construido.

Desafectos es una construcción metafórica llevada a cabo por familiares, hijos, bisnietos y amigos de desaparecidos en los Pozos de Caudé. Los trabajos forzosos eran una punición habitual en tiempos de guerra y posguerra, llamando en ocasiones a los prisioneros, represaliados y privados de sus libertades, desafectos. La división ideológica y territorial del estado español tras el alzamiento militar de 1936 tuvo una de sus mayores expresiones en los castigos y purgas de los considerados «responsables de cualquier hecho que por sus circunstancias y consecuencia deba estimarse como nocivo a los intereses del pueblo y del Gobierno» en zona sublevada, los oficialmente denominados «desafectos al régimen».

Simpatizantes de sindicatos, de partidos de izquierda o del Frente Popular recibían este apelativo al ser agrupados como Batallones de Trabajadores, subyugados y destinados al trabajo forzado. Estos Batallones, formados con el excedente de prisioneros de depósitos y campos de concentración, constituyeron durante la Guerra y la Posguerra Civil Española «el mayor sistema de trabajos en cautividad de la España contemporánea» y cubrieron la necesidad de infraestructuras y construcciones civiles. Muchos de los fusilados en los pozos habían sido forzados a trabajar construyendo para el régimen en la zona para posteriormente ser agrupados y fusilados en la explanada que hoy recuerda sus muertes.

El artista Abel Azcona viaja invitado por la Asociación Pozos de Caudé. Diseña y realiza una acción performativa con amigos, nietos y otros familiares. Durante horas, entre todos construyeron, en el lugar donde fueron arrojados los cuerpos de los 1005 fusilados, un muro de piedra y hormigón. Más de cincuenta personas colaboraron en la construcción de la instalación y al finalizar permanecieron una hora en frente del muro en señal de memoria, catarsis y empoderamiento. Un proceso íntimo y personal, donde todos ellos realizaron un ejercicio de justicia, memoria y reparación.

Curatorship Irene Ballester. With the collaboration of the Pozos de Caudé Association and the CollBlanc Gallery. Parallel exhibition with Desafectos and Buried by Abel Azcona at the Cultural Centre of Teruel. Currently one of the photographs of Desafectos is installed on the esplanade of Pozos de Caudé along with other installations by the artist. Photography: Bárbara Traver, Ian Dunham and Laura López.

Curaduría Irene Ballester. Con la colaboración de la Asociación Pozos de Caudé y la Galería CollBlanc. Exposición paralela con Desafectos y Enterrados de Abel Azcona en Centro Cultural de Teruel. En la actualidad una de las fotografías de Desafectos se encuentra instalada en la explanada de Pozos de Caudé junto a otras instalaciones del artista. Fotografía: Bárbara Traver, Ian Dunham y Laura López.

July, August, September 1936. The silence of the night was broken by the distant sound of trucks stopping near an old dilapidated inn located in front of Concud, a semi-hidden little town in a hollow a few kilometers away from Teruel. Then voices, screams, and a volley of shots, the echo that bounded with the abrupt sound of isolated detonations. Two, three, four and even ten on occasion. Again the silence and after a while the night breeze brought Concud the sound of the trucks moving away.

That sound scene was repeated night after night for several months, from July 1936 to December 1937. Not far from the sale, a farmer from Concud wrote down the shots he heard with the certainty that each stick he traced in his notebook represented a death. "I pointed more than a thousand," said the man, 35 years later, to Volnei and Jaurés Sánchez, two old Teruel socialists whose mother and sister made the last trip of their lives in one of those trucks.

There they killed them, there they gave them the coup de grace -a stroke in the farmer's notebook- and there they threw their bodies into the inn pit. They, María Pérez Macías and their daughter Pilar, are two of the 1,005 people shot whose remains rest in the so-called Caudé wells.

The old inn, now non-existent, was built next to a well 84 meters deep and of just over two meters in diameter, located at kilometer 126 of the N-234 from Sagunto to Burgos; next to Teruel, on the way to Zaragoza. The well, one only and located in the vicinity of Concud, is paradoxically called Caudé, another neighboring town but further away than the first.

The dramatic events that took place there have remained hidden but not forgotten for sixty years. Now, relatives of the victims, with the collaboration of the ideological heirs of those shot, have strived to recover their memory, joining, perhaps unknowingly, an unstoppable current that tries to retell the recent history of Spain as it was as painful as may be. A path started two years ago when Emilio Silva, grandson of a Republican Left sympathizer who owned a colonial shop in Villafranca del Bierzo, which he named La Favorita, decided to look for the remains of his grandfather, who was killed by a shot in the neck, the morning of October 16, 1936 in a place near Priaranza (León).

In Caudé the identity of the majority of the thousand dead thrown into the well is not known. In fact, there are hundreds of families living in towns or hamlets in the area who do not know for sure where the remains of their relatives are who, one day in 1936, were taken away never to return. Families from Teruel, Santa Eulalia, Gea de Albarracín, Villarquemado, Concud, Caudé, Dos Torres, Las Cuevas and many more places.

Since the end of the war to the establishment of democracy, no one ventured to approach the well openly, which did not prevent there always being some bouquet of flowers hidden by those who did not want to forget. But during that time, there was another event that the local people observed from afar. "It was shortly before the Valle de los Caídos was inaugurated, perhaps in 1958," recalls Jaurés."

An official truck came, they removed the earth, took out some bones and took them to the Valley because they wanted there to be remains from all Spain." That is the only time that the well is known to have been dug.

After the socialist electoral victory of 1982, the flowers began to be deposited without much fear. One of the days when the Sánchez brothers had come to leave their bouquet, a "farmer, older, smaller and walking with a cane" approached them. After asking them if he had relatives at the well, he told them that before dying he wanted to tell them what he had lived through. Then he related to them how from Concud he heard the trucks at night and wrote down in a notebook the coup de grace with which they finished off the shot. He also told them that every morning the townspeople confirmed what had happened.

The peculiar way of evaluating the deaths of the farmer resulted in a figure - "a few more than a thousand" - which confirmed another more scientific but no less dramatic account, and they all concluded that there were 1,005 bodies in Caudé. If they were more or less no one knows, although witnesses assure that the Well was completely filled with corpses to the extent that they had to dig trenches in its vicinity where they buried more victims.

Today, at the curb, someone has written in red paint "an 84-meter-deep artesian well full of those shot in 1936. A memory of your companions." The inscription is part of the austere and modest monument in their memory erected in 1980 with the good will of those who have not wanted to forget them. A monument that cost 119,636 pesetas and to which nine families have added, in the form of a tombstone, their personal tribute.

This phenomenon, which represents the recovery of the memory of those who died for the Republic, spreads spontaneously throughout Spain, but at an uneven rate. Thus, while in Teruel it could be said that it is beginning, in León or Burgos the exhumations have already received an appellation that defines them as: "The archeology of reconciliation".

Eduardo Martín Pozuelo

Julio, agosto, septiembre de 1936. El silencio de la noche se rompía con el sonido lejano de los camiones que paraban cerca de una vieja venta ruinosa situada frente a Concud, un pueblecito semioculto en una hondonada a pocos kilómetros de Teruel. Luego, unas voces, unos gritos y una salva de disparos cuyo eco enlazaba con el brusco sonido de unas detonaciones aisladas. Dos, tres, cuatro y hasta diez en alguna ocasión. De nuevo el silencio y al rato la brisa nocturna acercaba hasta Concud el rumor de los camiones que se alejaban.

Aquella escena sonora se repitió noche tras noche durante varios meses, desde julio de 1936 hasta diciembre de 1937. No muy lejos de la venta, un labrador de Concud apuntaba en un cuaderno los tiros que oía con la certeza de que cada palote que trazaba en su libreta representaba una muerte. "Apunté alguno más de mil", dijo el hombre, 35 años después, a Volnei y Jaurés Sánchez, dos viejos socialistas turolenses cuya madre y hermana hicieron el último viaje de su vida en uno de aquellos camiones. Allí las mataron, allí les dieron el tiro de gracia -un trazo en la libreta del labrador- y allí arrojaron sus cuerpos al pozo de la venta. Ellas, María Pérez Macías y su hija Pilar, son dos de las 1.005 personas fusiladas y rematadas cuyos restos reposan en los llamados pozos de Caudé. La vieja venta, hoy inexistente, se levantaba junto a un pozo de 84 metros de profundidad y algo más de dos de diámetro que se encuentra en el kilómetro 126 de la N-234 de Sagunto a Burgos; es decir, al lado de Teruel, camino de Zaragoza. El pozo, uno solo y que se ubica en las proximidades de Concud, es paradójicamente denominado con el nombre de Caudé, otro pueblo vecino pero más alejado que el primero.

Los dramáticos sucesos acaecidos en aquel lugar han permanecido ocultos pero no olvidados durante sesenta años. Ahora, parientes de las víctimas, con la colaboración de los herederos ideológicos de aquellos fusilados, se han empeñado en recuperar su memoria, sumándose, quizá sin saberlo, a una imparable corriente que intenta contar de nuevo la reciente historia de España tal como fue y por dolorosa que ésta sea. Un camino iniciado hace dos años cuando Emilio Silva, nieto de un simpatizante de Izquierda Republicana que era propietario en Villafranca del Bierzo de una tienda de coloniales a la que puso de nombre La Favorita, decidió buscar los restos de su abuelo al que mataron de un tiro en la nuca, la madrugada del 16 de octubre de 1936 en un paraje cercano a Priaranza (León). En Caudé no se conoce la identidad de la mayoría de los mil muertos arrojados al pozo. De hecho, se cuentan por centenas las familias habitantes en pueblos o caseríos de la zona que no saben a ciencia cierta dónde se hallan los restos de aquel familiar que un día de 1936 se lo llevaron para no volver jamás. Las hay de Teruel capital, de Santa Eulalia, de Gea de Albarracín, de Villarquemado, de Concud, de Caudé, de Dos Torres, de Las Cuevas y de muchos más lugares.

Desde el final de la guerra hasta la instauración de la democracia nadie aventuraba acercarse al pozo abiertamente, lo que no impidió que siempre hubiera algún ramo de flores depositado a escondidas por los que no querían olvidar. Pero durante ese tiempo, hubo otro acontecimiento que las gentes del lugar observaron desde lejos. "Fue poco antes de inaugurase el Valle de los Caídos, quizá en 1958", recuerda Jaurés. "Vino un camión oficial, removieron la tierra, sacaron unos huesos y se los llevaron al Valle por aquello de que hubieran restos de toda España." Esa es la única vez, que se sepa, que se ha excavado el pozo. Tras la victoria electoral socialista de 1982, las flores comenzaron a depositarse sin tanto temor. Uno de los días que los hermanos Sánchez habían acudido dejar su ramo, un "labrador, ya mayor, pequeño y que caminaba con un bastón" se acercó hasta ellos. Tras preguntarles si tenía familia en el pozo, les dijo que antes de morir quería contarles lo que había vivido. Entonces les relató cómo desde Concud oía por la noche los camiones y apuntaba en una libreta los tiros de gracia con los que remataban a los fusilados. También les dijo que cada mañana la gente del pueblo confirmaba lo sucedido.

La peculiar forma de evaluar muertes del labrador dio como resultado una cifra -"alguno más de mil"- que vino a confirmar otro recuento más científico pero no menos dramático, entre todos llegaron a la conclusión de que en Caudé había 1.005 cuerpos. Si hay más o menos nadie lo sabe, aunque los testigos aseguran que el pozo se llenó totalmente de cadáveres hasta el extremo de que abrieron zanjas en sus proximidades donde enterraron a más víctimas.

Hoy, en el brocal, alguien ha escrito con pintura roja "pozo artesiano de 84 metros de profundidad lleno de fusilados en 1936. Un recuerdo de vuestros compañeros". La inscripción forma parte del austero y modesto monumento en su memoria levantado en 1980 con la buena voluntad de quienes no han querido olvidarlos. Un monumento que costó 119.636 pesetas y al que nueve familias han añadido, en forma de lápida, su homenaje personal.

Este fenómeno, que representa la recuperación de la memoria de los muertos por la República, se extiende espontáneamente por España, pero a ritmo desigual. Así, mientras en Teruel podría decirse que comienza, en León o Burgos las exhumaciones son un hecho que ya recibido un apelativo que lo define: "La arqueología de la reconciliación".

Eduardo Martín Pozuelo