Nine Steps Towards the Mother, and actually some more, can be understood as a complete process work or a compendium of numerous works that took place from October 2023 to April 2025. All of Abel Azcona's actions, documentary works and installations around the maternal figure during these dates are understood as such. The initial idea was a full year and to conceive the process in nine clear steps, however, after the curatorial and artist's decision to postpone the final meeting between mother and son to the exact date of April where the abandonment took place thirty-seven years ago, new pieces and creations on this theme emerged due to the artist's pure need to respond to questions prior to the final performance. The final meeting between mother and son will take place in a museum to be decided, during the first months of 2025. «The hardest, most intimate, and generous work by Abel Azcona to date. After more than twenty years of works in continuous search of his own mother and for healing and acceptance of his own orphanhood, the appearance of his biological maternal figure transforms the meaning and potential of his work.»

Nueve pasos hacia la madre, y en realidad algunos más, puede ser entendida como una obra procesual total o con un compendio de numerosas obras acontecidas desde octubre del 2023 a abril del 2025. Todas las acciones, obras documentales e instalaciones de Abel Azcona en torno a la figura materna durante estas fechas son entendidas como tal. La idea inicial era un año completo y concebir el proceso en nueve pasos claros, no obstante, tras la decisión curatorial y del artista de retrasar el encuentro final entre madre e hijo a la fecha exacta de abril donde treinta y siete años atrás aconteció el abandono, surgieron nuevas piezas y creaciones de esta temática por la pura necesidad del artista de responder a cuestiones previas a la performance final. El encuentro final entre madre e hijo acontecerá en un museo por decidir, durante los primeros meses de 2025. «La obra más dura, intima y generosa de Abel Azcona hasta la fecha. Tras más de veinte años de obras en continua búsqueda de su propia madre y de sanación y aceptación de su propia orfandad, la aparición de su figura materna biológica transforma el significado y potencial de su obra.»

Frames of Isabel Gómez Aranda, the biological mother of Abel Azcona, narrating her life experience during Nine Steps Towards the Mother at the Contemporary Art Center of Málaga. / Fotogramas de Isabel Gómez Aranda, madre biológica de Abel Azcona narrando su experiencia vital durante Nueve pasos hacia la madre en el Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Málaga.

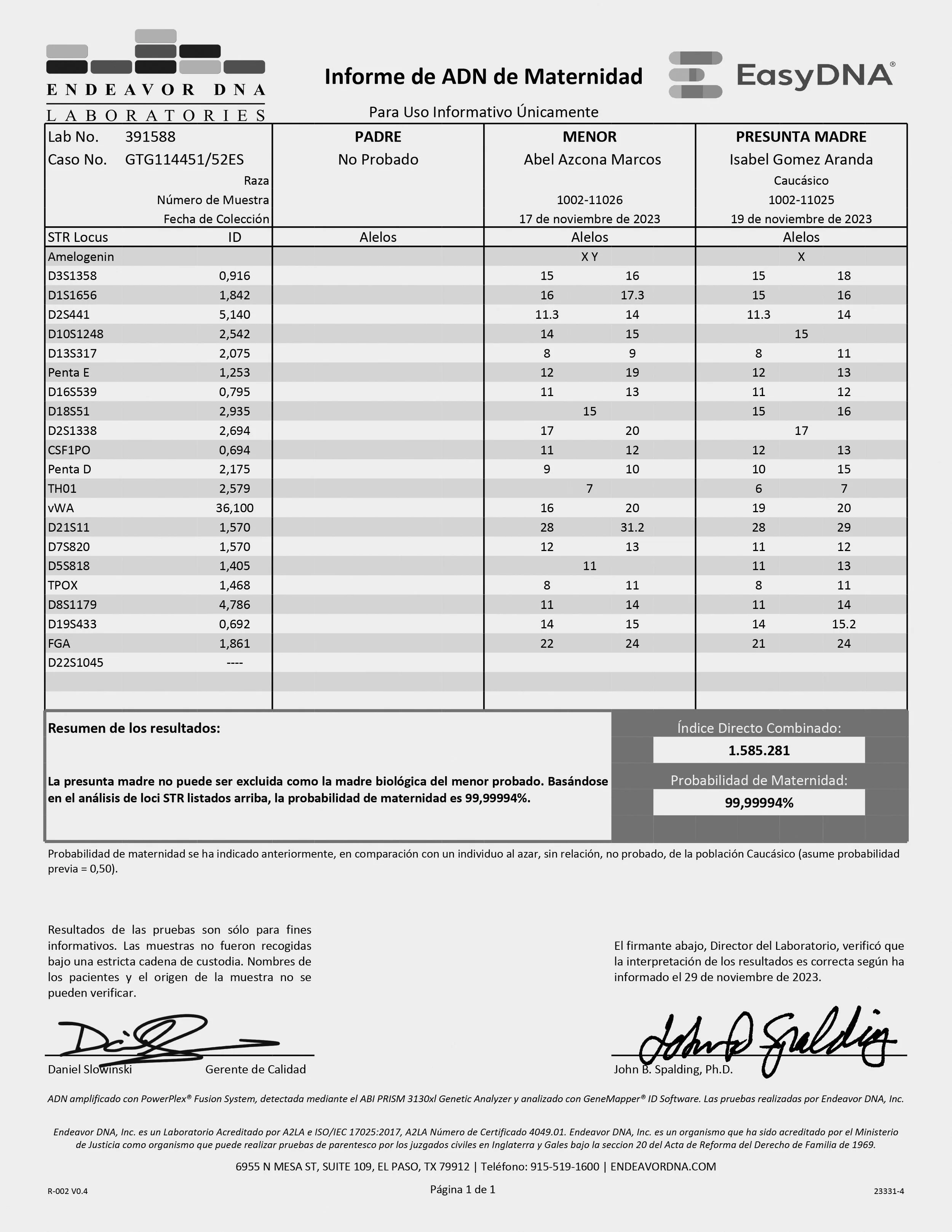

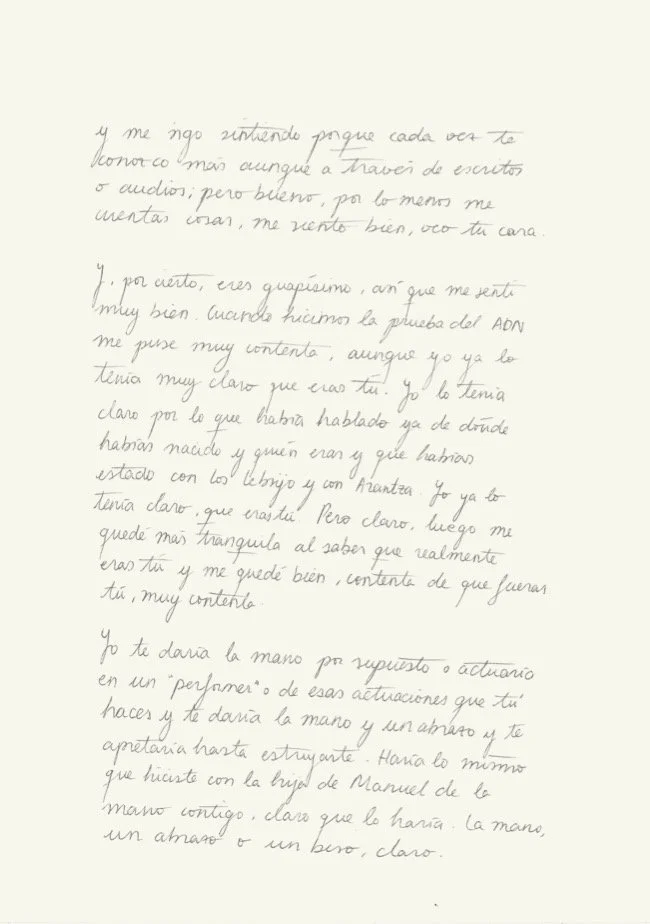

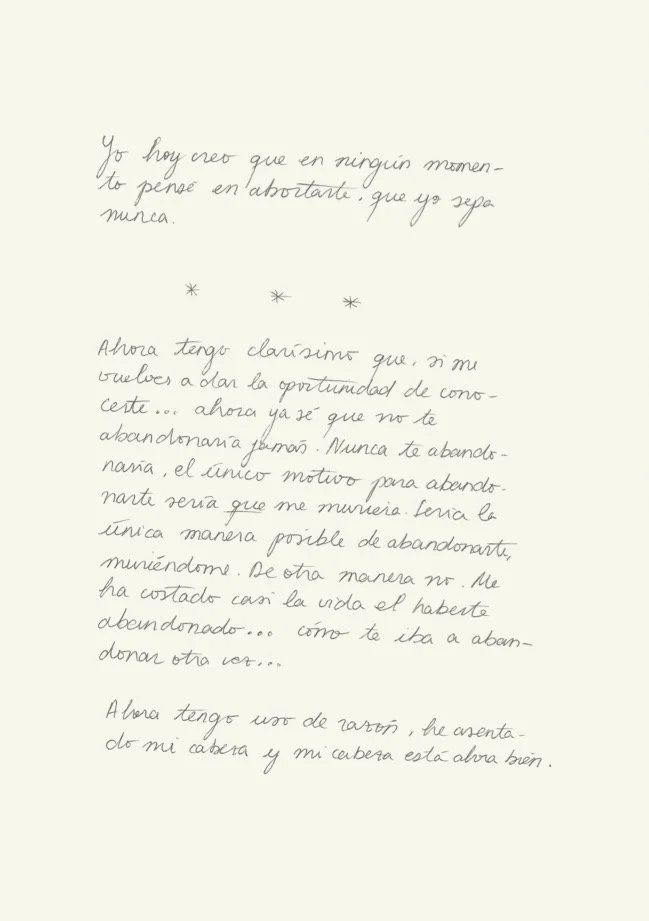

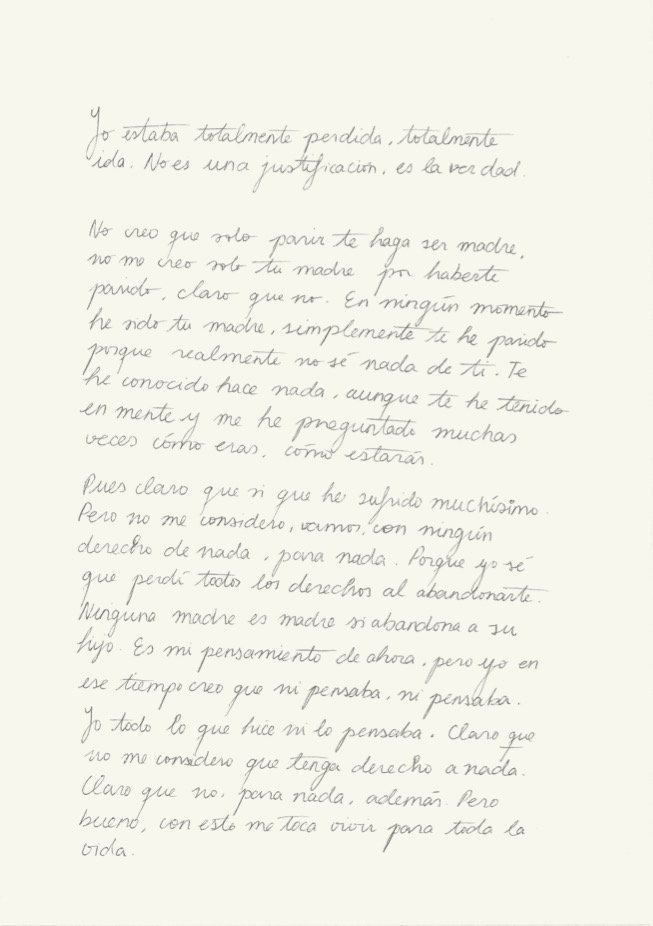

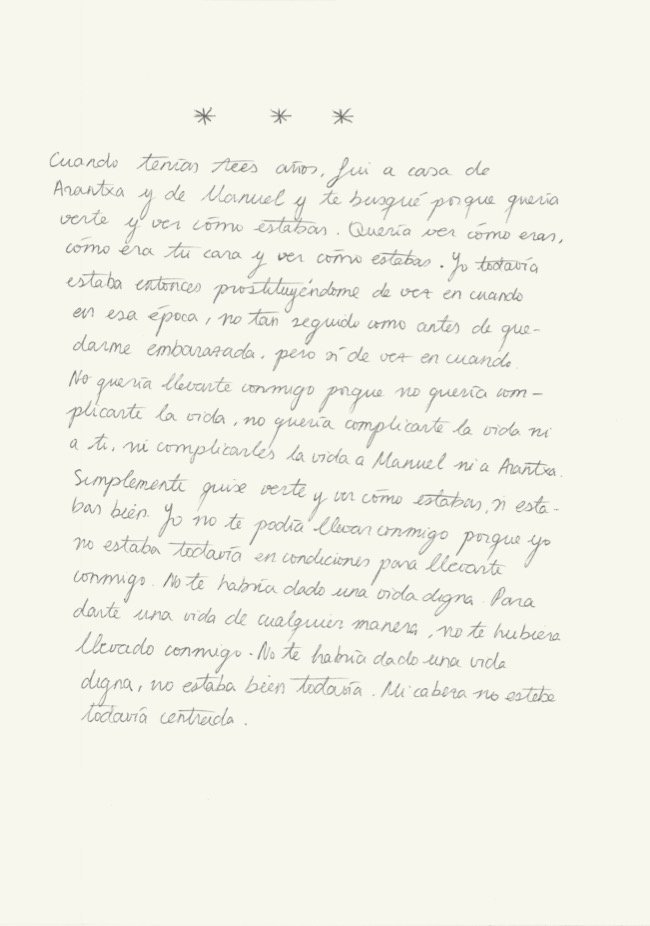

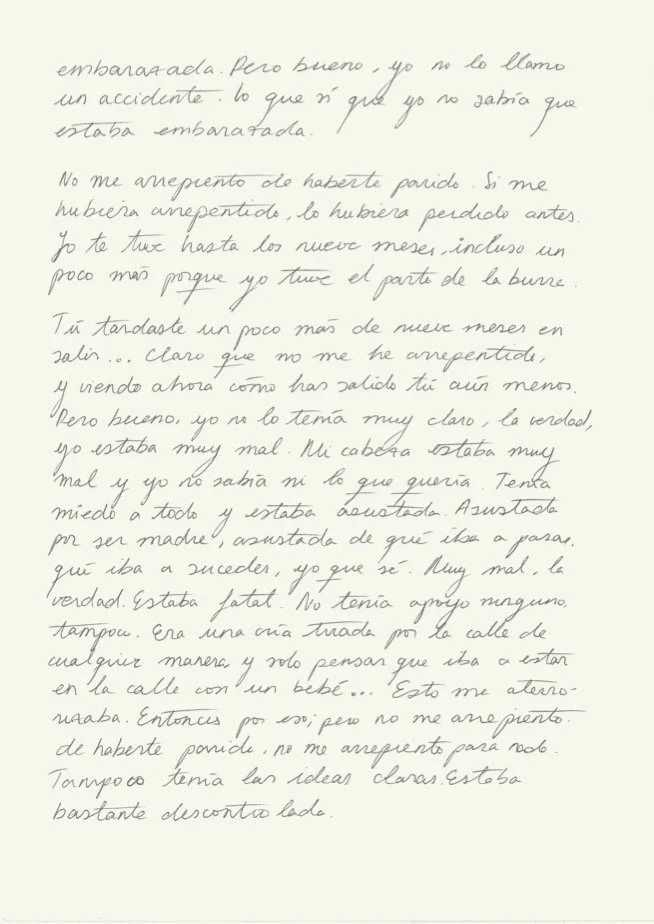

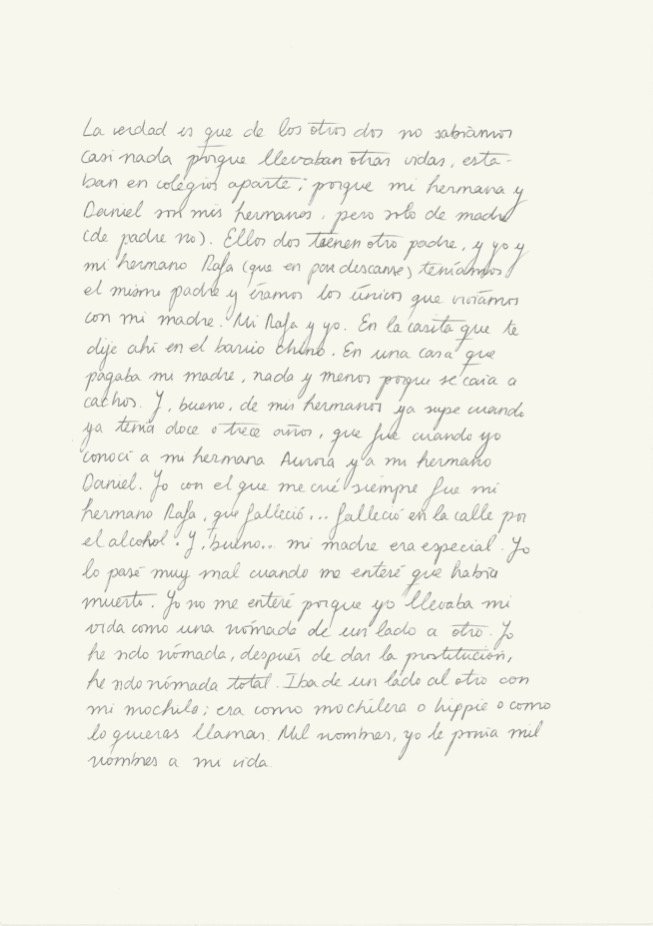

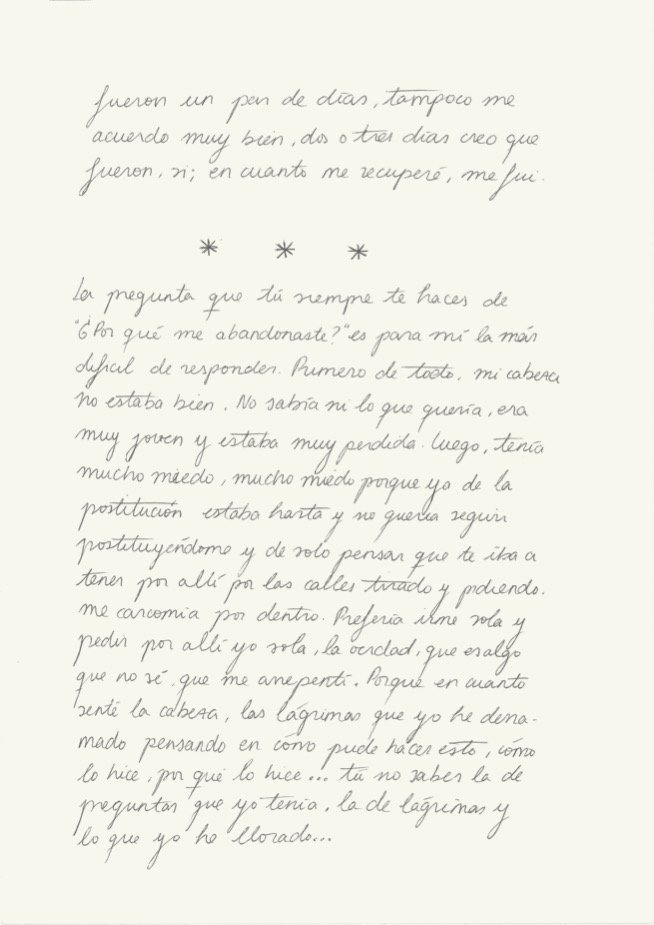

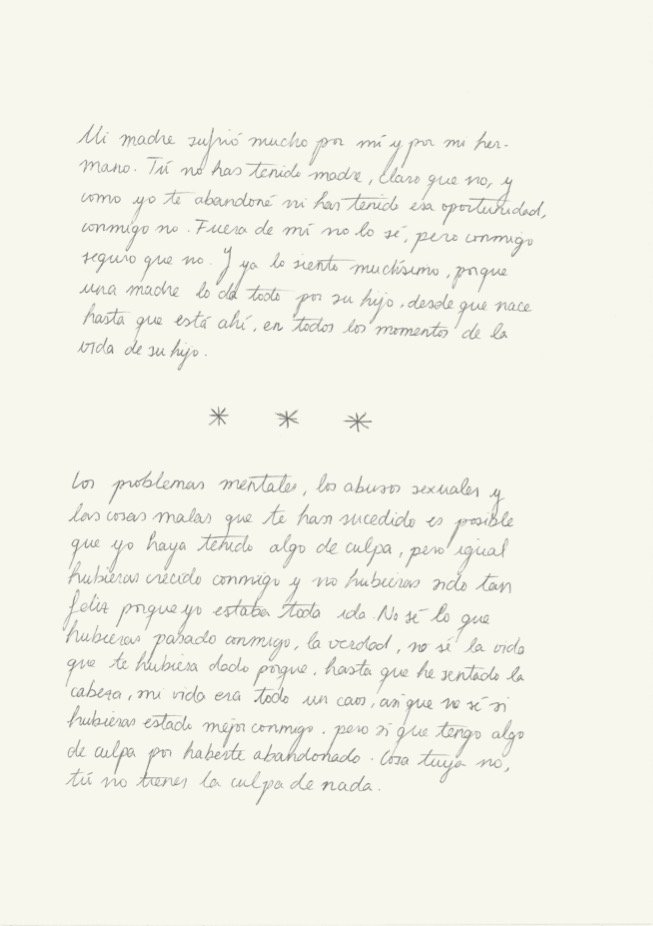

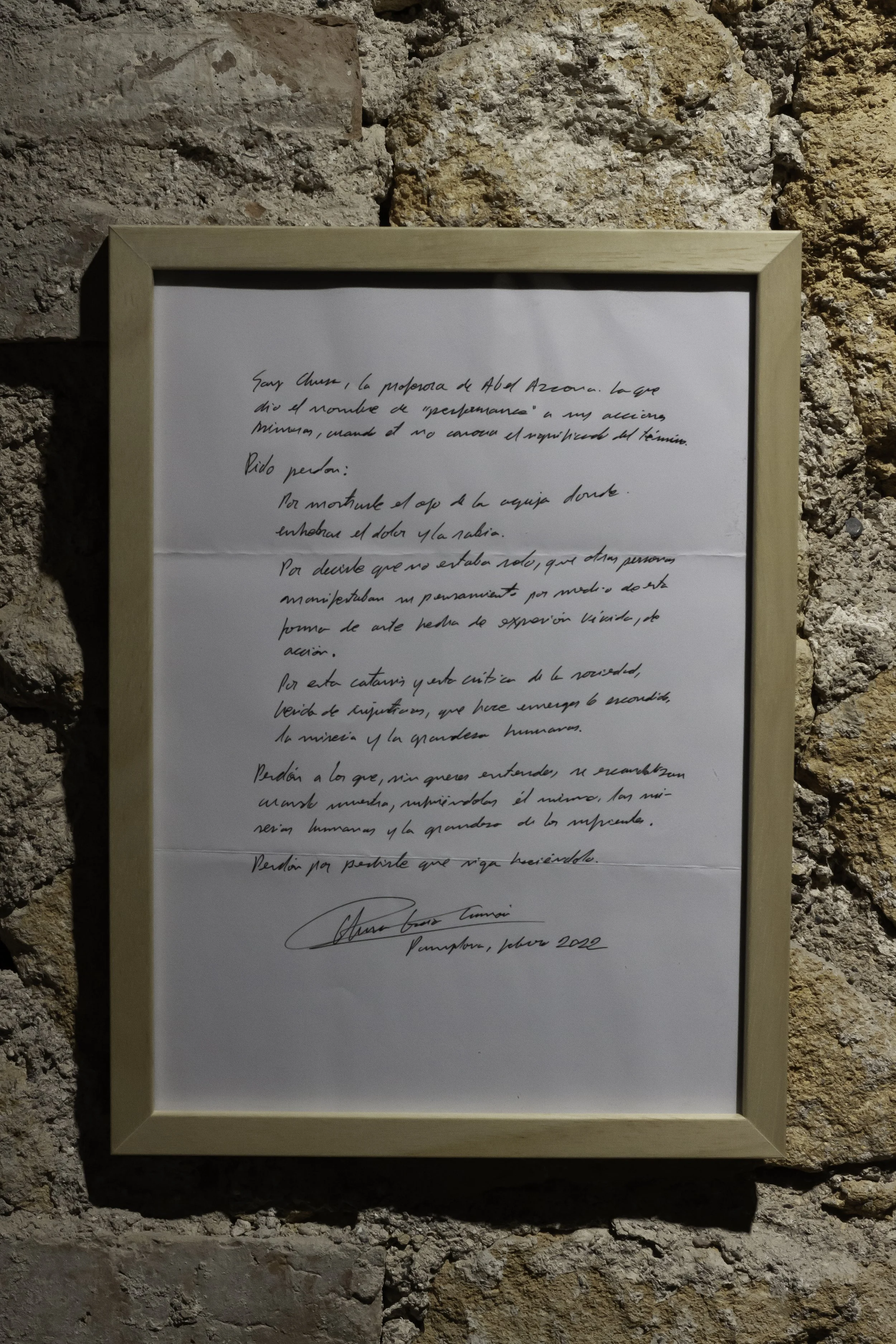

First full exhibition featuring the work Exégesis de la madre at the Art Center Cuartel de Artillería in the city of Murcia. This handwritten work contains the testimony and history of Abel Azcona's biological mother. / Primera exposición completa con la obra Exégesis de la madre en el Centro de Arte Cuartel de Artillería en la ciudad de Murcia. Obra manuscrita con el testimonio e historia de la madre biológica de Abel Azcona.

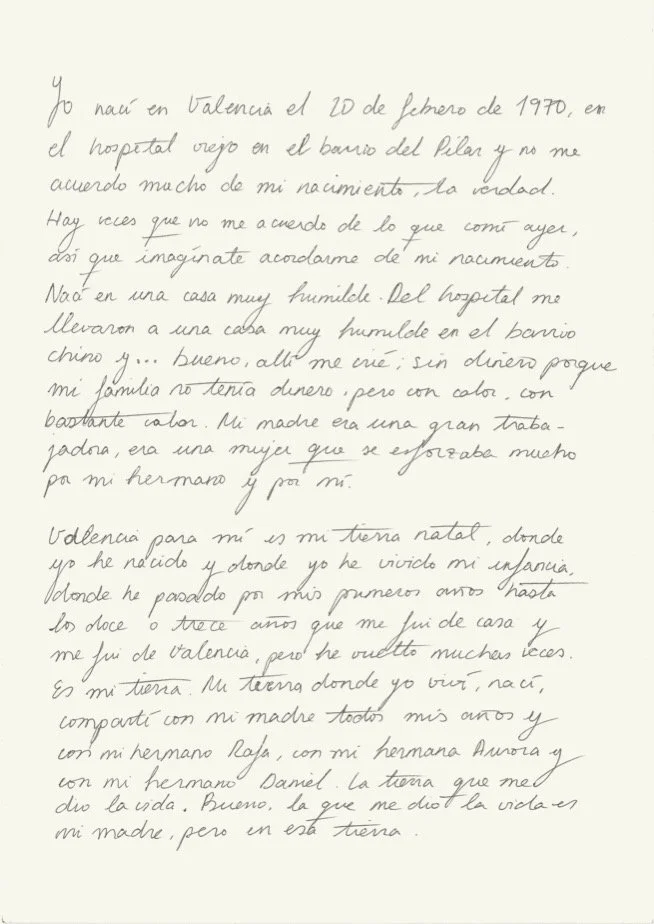

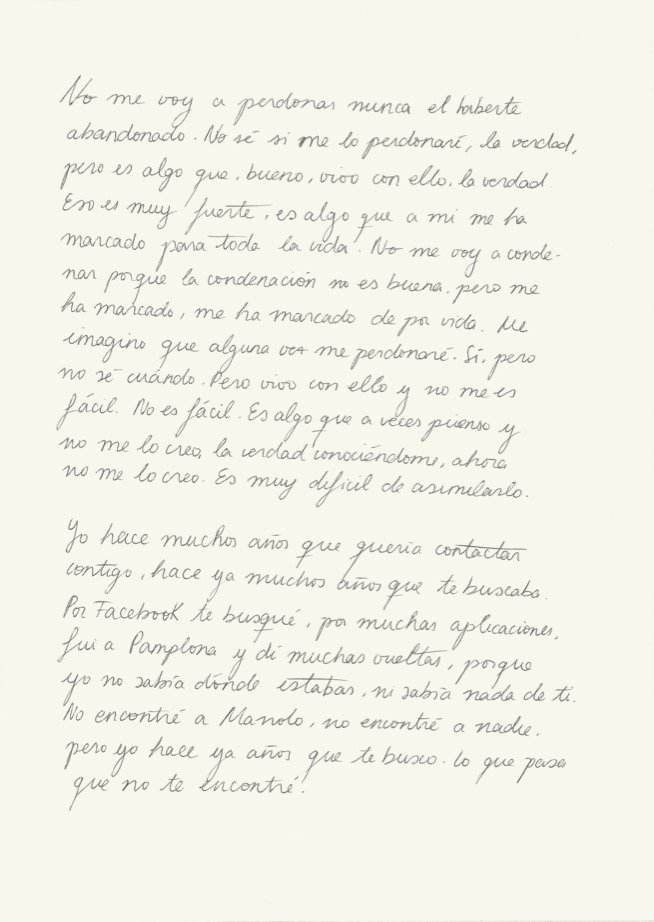

First pages of the work Exegesis of the Mother. A handwritten work with the testimony and history of Abel Azcona's biological mother. One of the steps taken by the mother before they met in person. / If you have any more text you need translated or have questions about, feel free to share!Primeras hojas de la obra Exégesis de la madre. Obra manuscrita con el testimonio e historia de la madre biológica de Abel Azcona. Uno de los pasos de la madre antes de conocerse ambos en persona.

First step. First contact of the mother with the artist. / Primer paso. Contacto por primera vez de la madre con el artista.

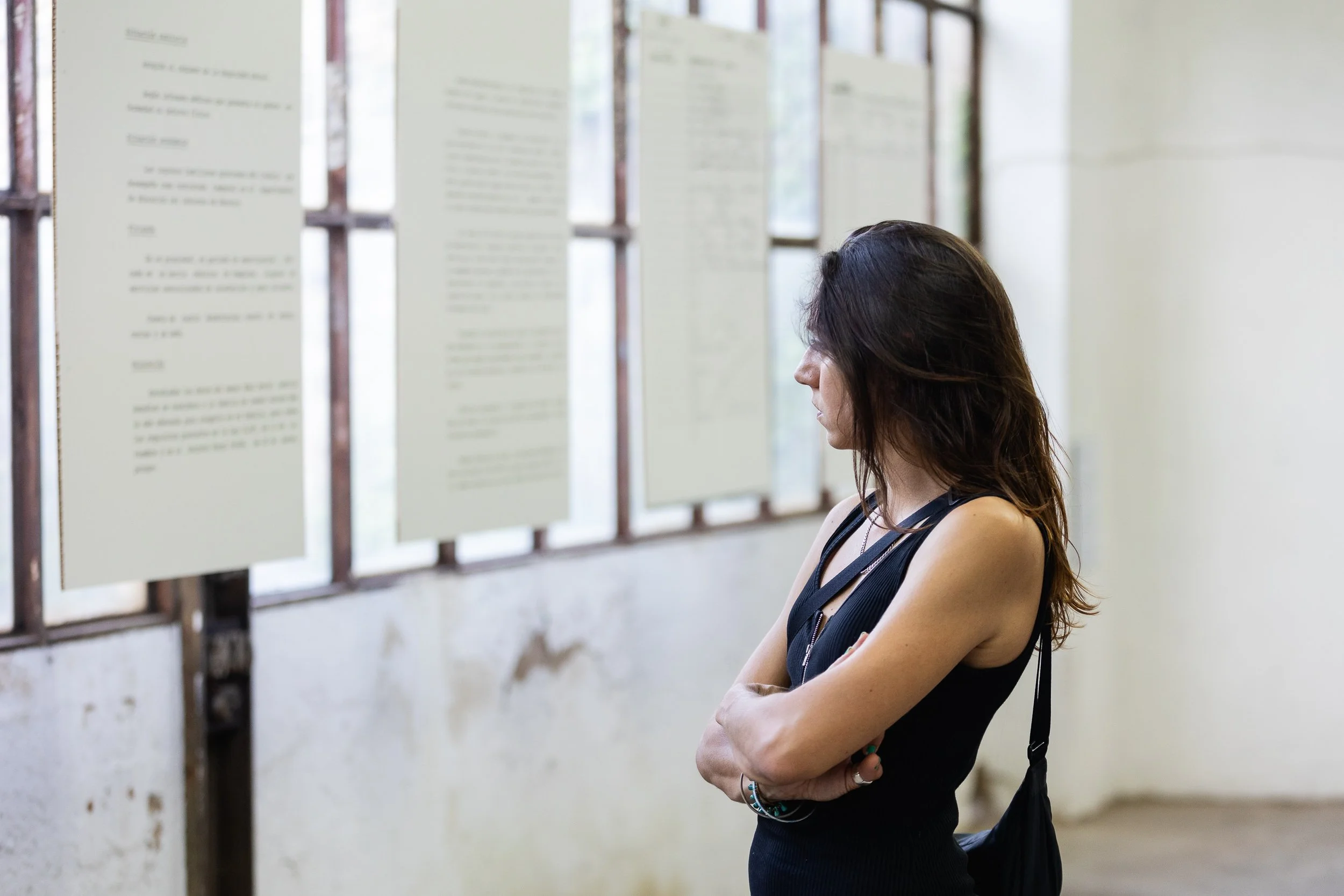

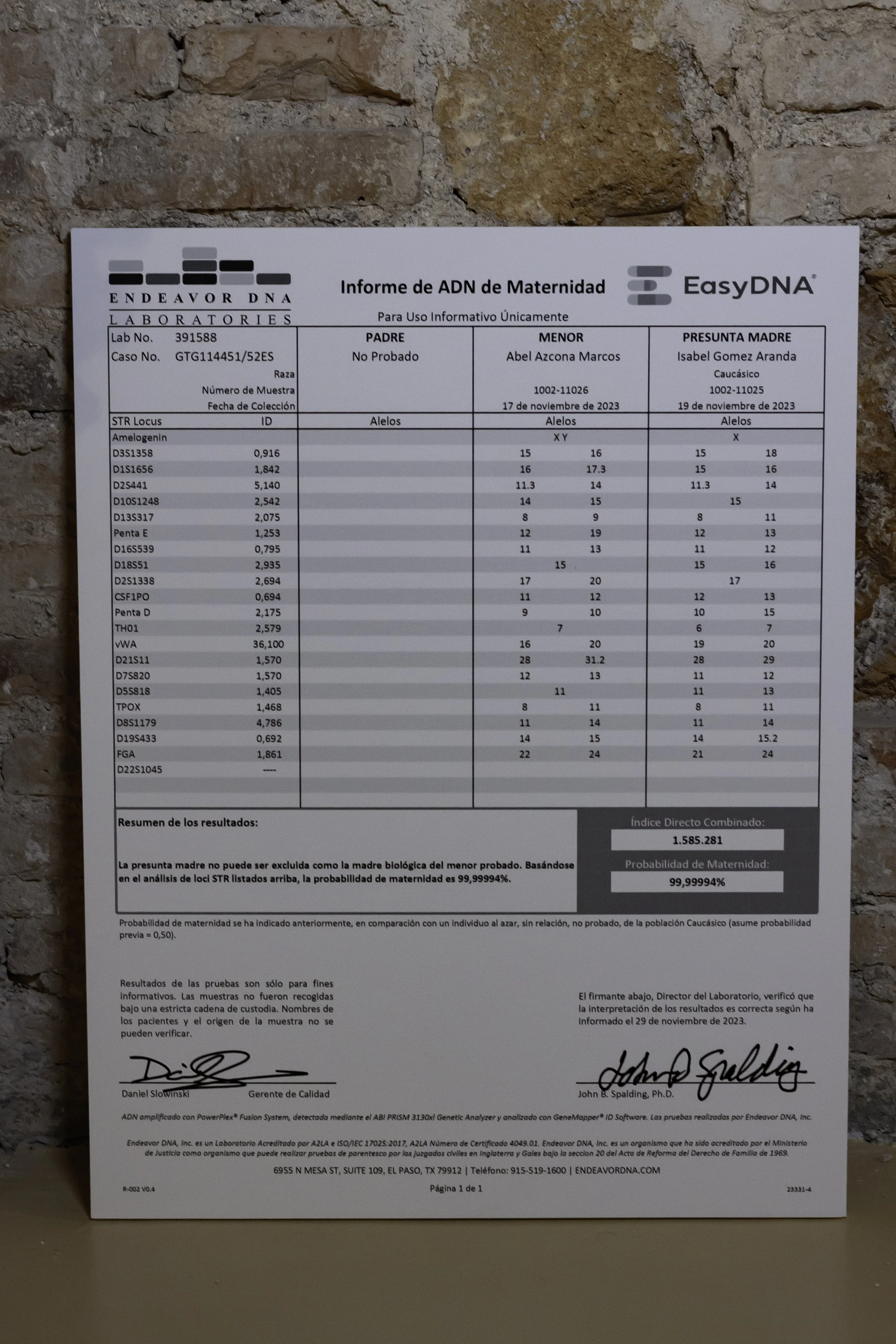

Second step. Abel Azcona during the performance of reading the DNA test result at the La Panera Art Center and Final DNA Test. Document resolved during the performance at the La Panera Art Center. / Segundo paso. Abel Azcona durante la performance de la lectura del resultado de la prueba de ADN en el Centro de Arte La Panera y Prueba de Adn final. Documento resuelto durante la performance en el Centro de Arte La Panera.

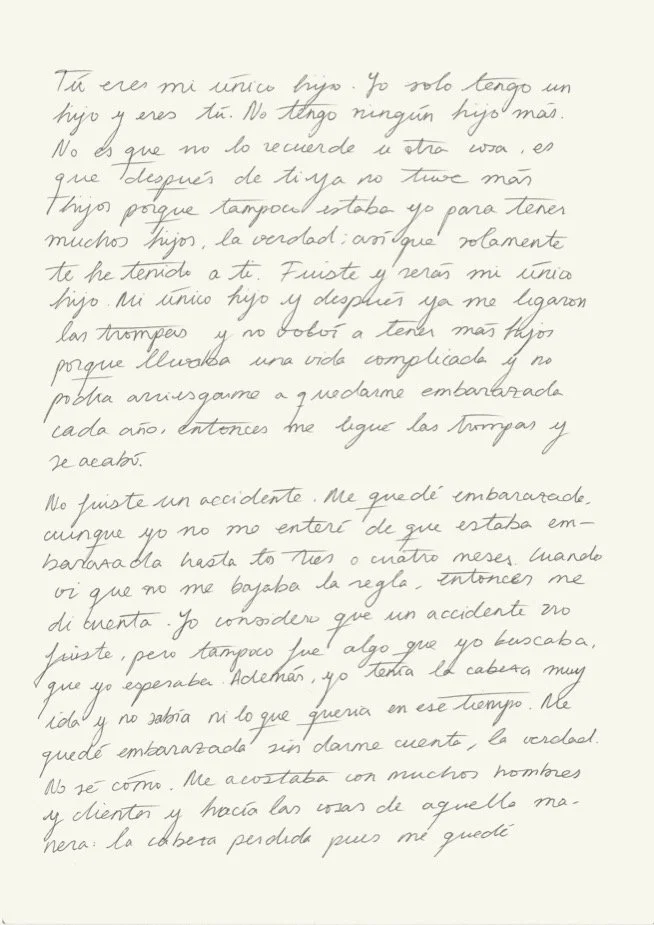

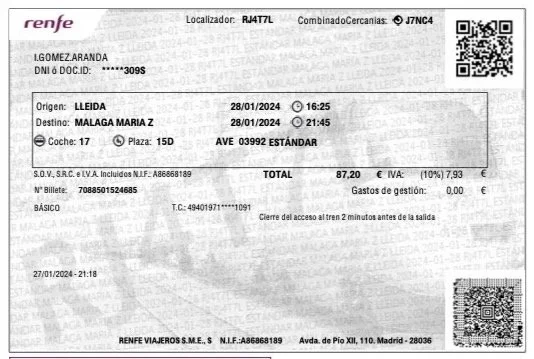

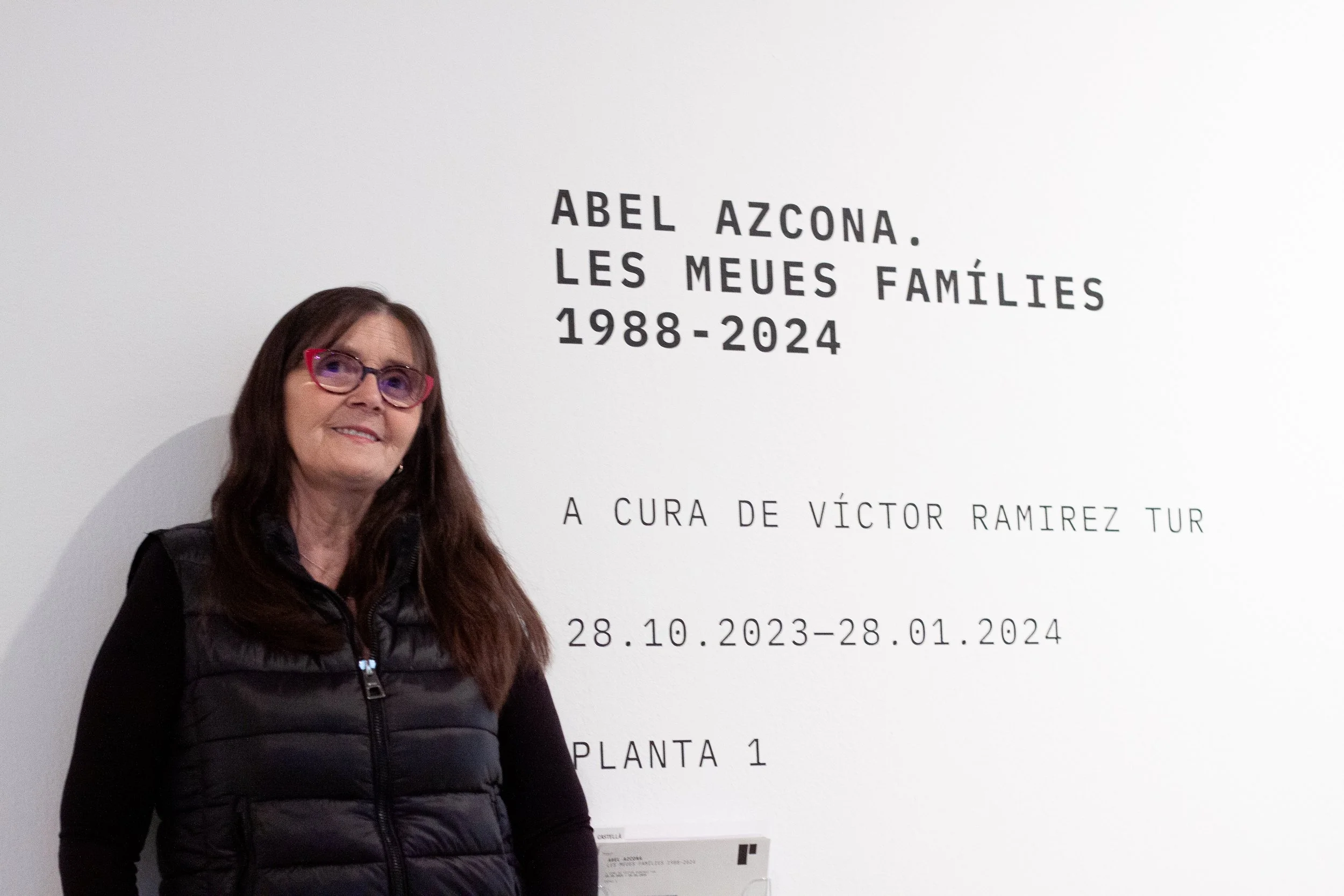

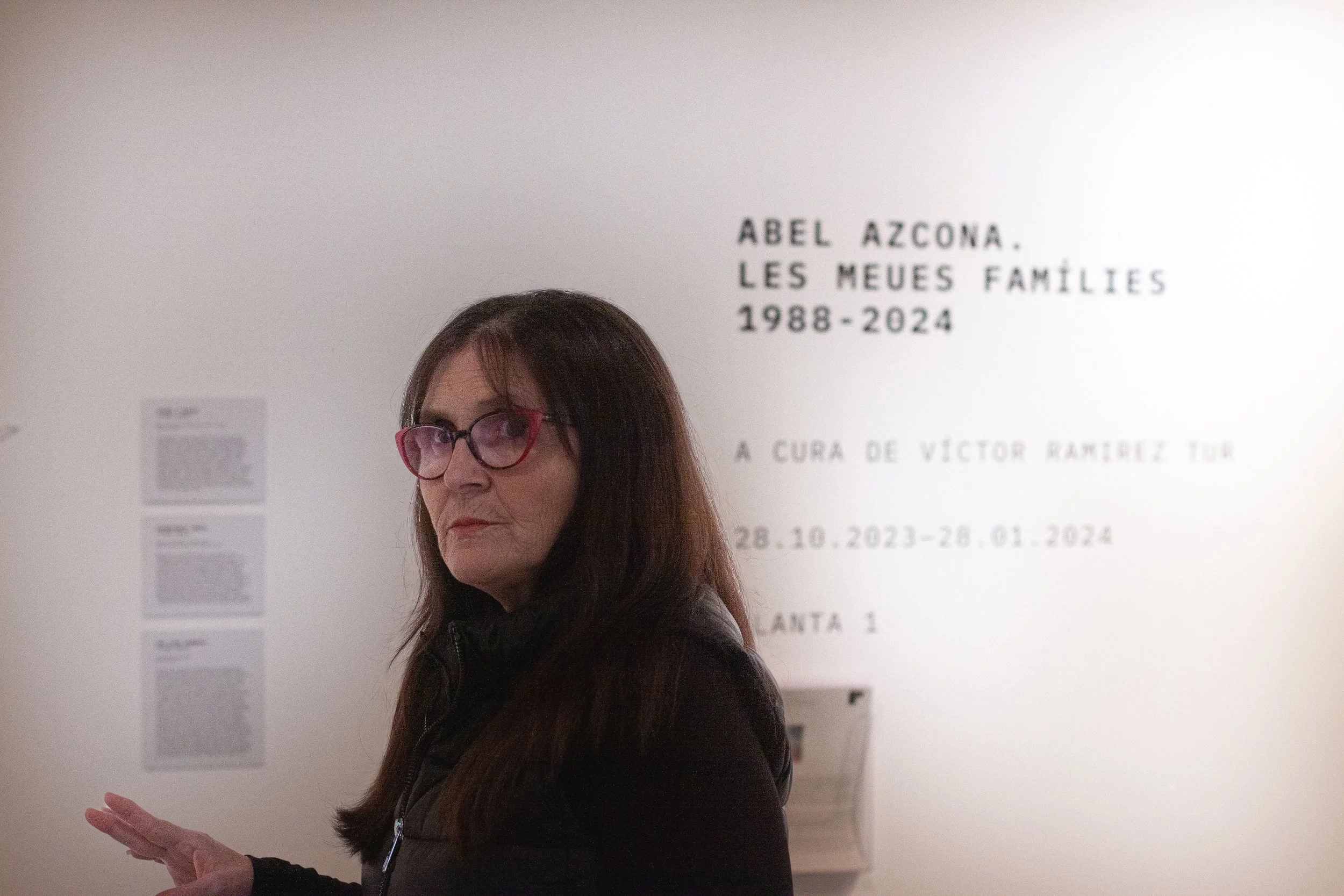

Third step. Visit of the mother, Isabel Gómez Aranda, to the closing of the exhibition "My Families 1988-2024" at the La Panera Art Center. / Tercer paso. Visita de la madre Isabel Gómez Aranda a la clausura de la exposición Mis familias 1988-2024 en el Centro de Arte La Panera.

Fourth step. Handwritten account by the biological mother detailing her life experience and her version of events. / Cuarto paso. Relato manuscrito de la madre biológica con su experiencia vital y su versión de los hechos.

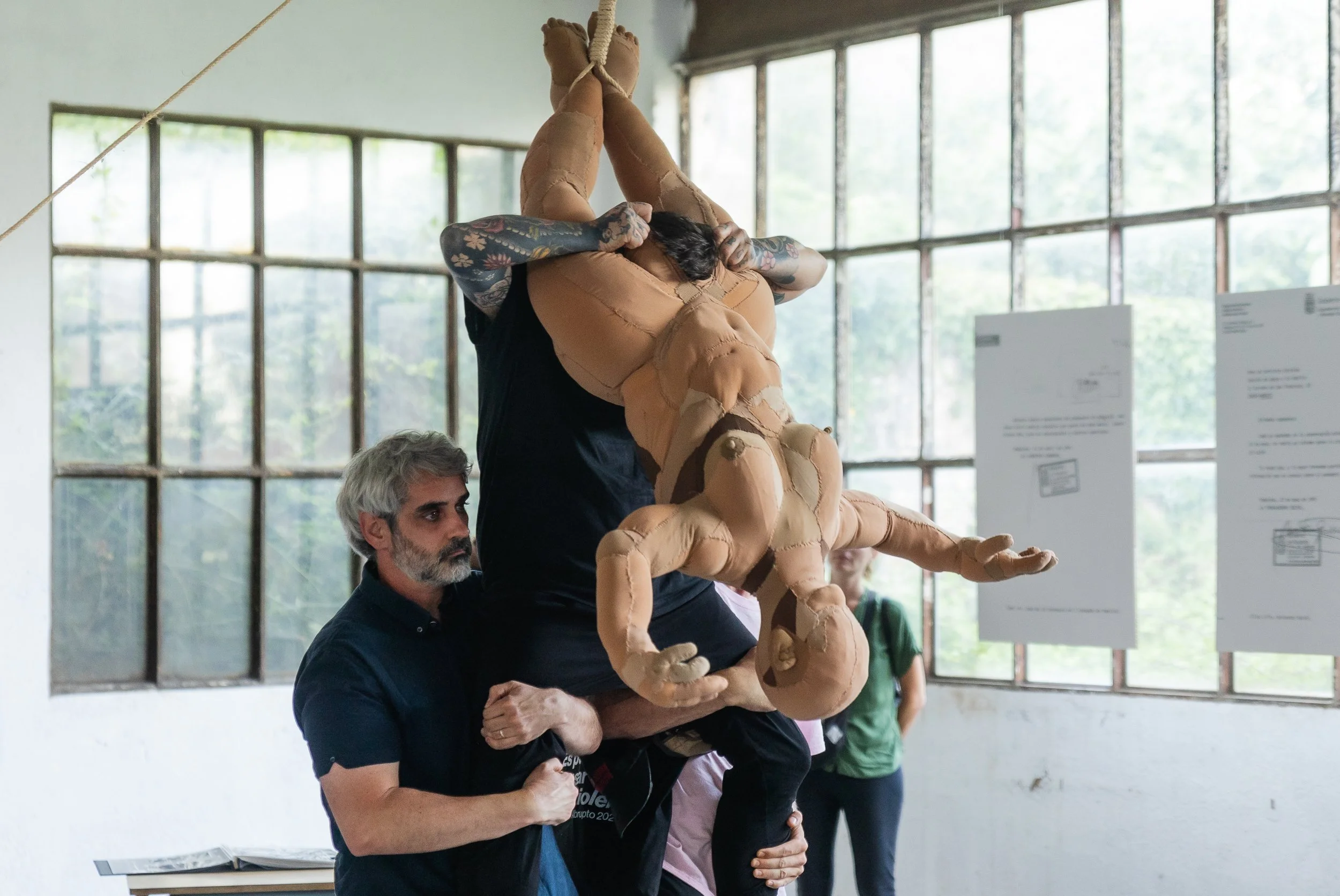

Fifth step. The exposed mother. For the first time, the mother is exhibited and performative in a museum on the same pedestal where she will meet the artist in the final step. / Quinto paso. La madre expuesta. Por primera vez la madre se expone y performatiza en un museo en la misma peana donde conocerá al artista en el último paso.

Sixth step. The mother tells her story in the first person through a collection of documentary video art pieces. / Sexto paso. La madre cuenta su relato en primera persona mediante una colección de piezas de videoarte documental.

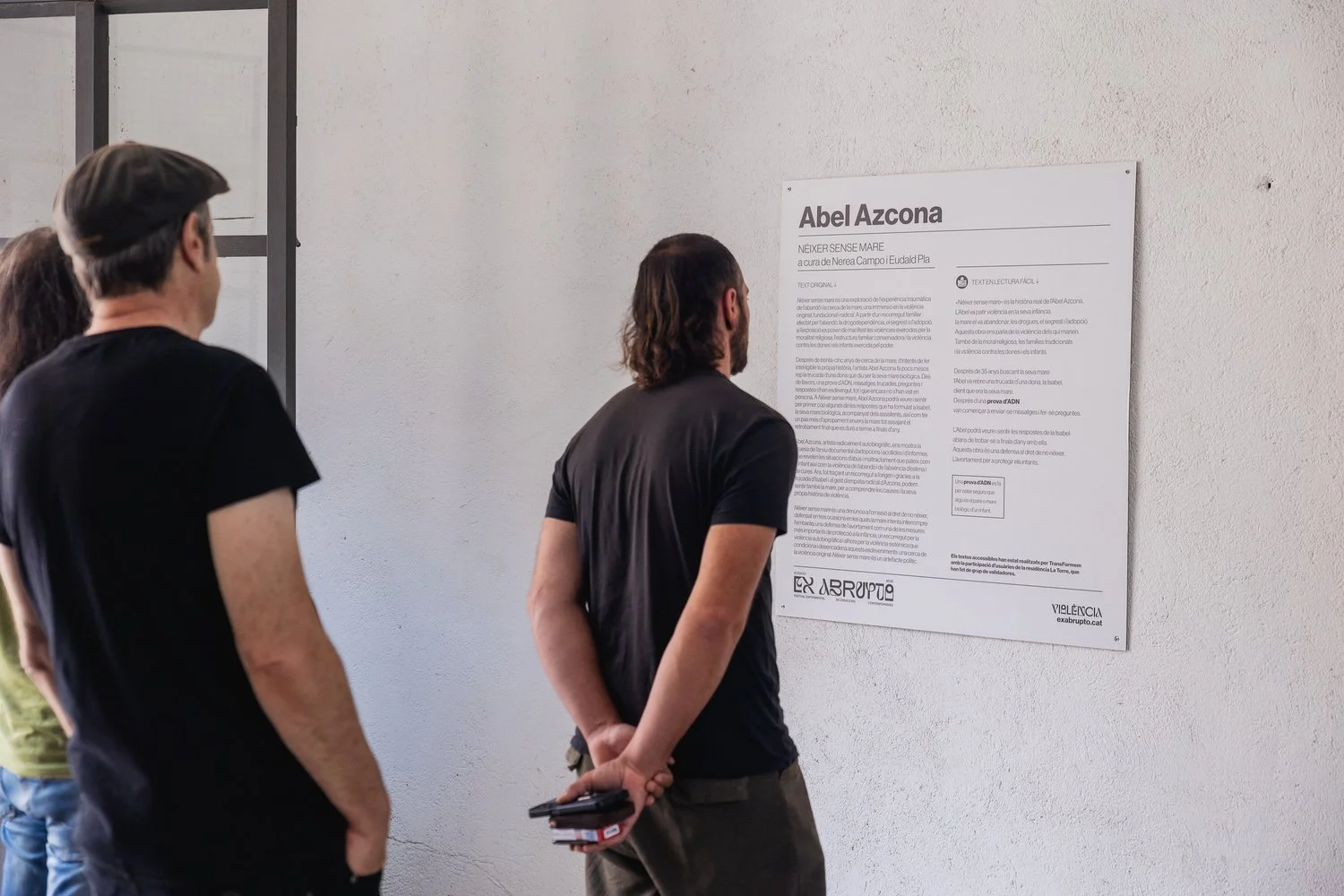

Seventh step. An exhibition serving as a recapitulation of all the steps taken so far, along with the activation of nine brief performances related to the mother. / Séptimo paso. Exposición a modo de recapitulación de todos los pasos hasta el momento y activación de nueve performances breves hacia la madre.

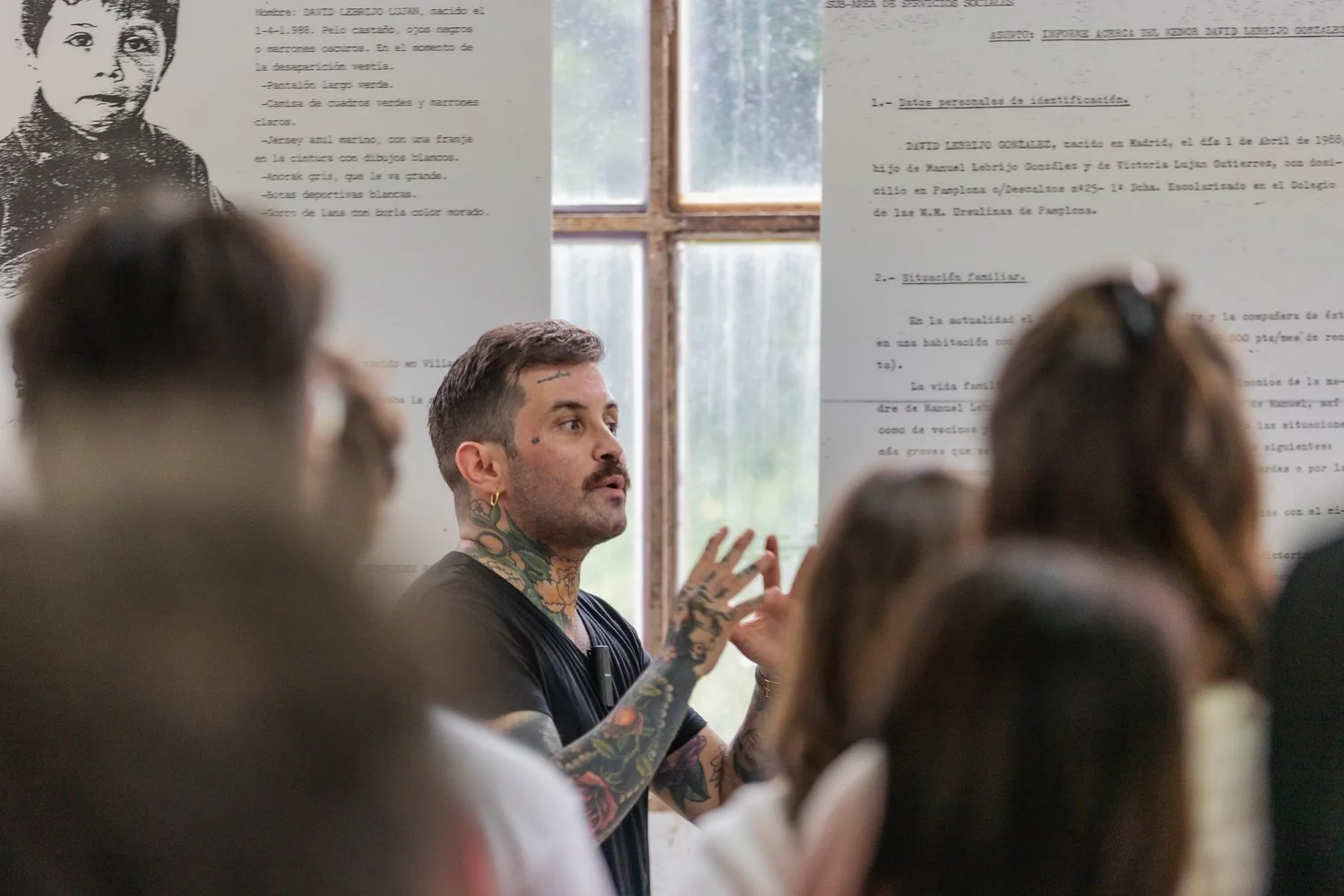

Eighth step. Various performative phases within the exhibition "Abel Azcona and The Role of the Family" at the Artillery Barracks of Murcia. Curated by Pedro A. Cruz. / Octavo paso. Diferentes fases performativas en el marco de la muestra Abel Azcona I El Papel de la Familia en el Cuartel de Artillería de Murcia. Comisariado por Pedro A. Cruz.

The final performance is a work in itself, but it can also be understood as the final step of the nine steps toward the mother. It will take place during the first months of 2025. / La performance final es una obra en si pero también puede entenderse como el paso final de los nueve pasos hacia la madre. Se desarrollará durante los primeros meses del año 2025.

Ninth step. The final encounter between the mother (Isabel Gomez Aranda) and the son (Abel Azcona) after never having seen each other since April 3, 1988. This is the date when the mother abandoned the future artist while he was in the incubator, having been born with fetal alcohol syndrome. / Noveno paso. Encuentro final entre la madre (Isabel Gomez Aranda) y el hijo (Abel Azcona) tras no haberse visto nunca desde el 3 de abril de 1988. Fecha en el que la madre abandonó al futuro artista en mientras se encontraba en la incubadora al haber nacido con alcoholismo fetal.

Abel Azcona's constant search for his own identity, marked by violence such as child abuse, abandonment, or alienation, has positioned him as a male figure advocating for abortion rights, women's rights, and against violence, precisely based on his own history. On the other hand, the mother's story is marked by the vulnerability of drug addiction, being forced into prostitution, subsequently abandoning her son, or experiencing sexual assaults. Her story embodies the vulnerability of women who suffer violence simply because of their gender, here epitomized in a specific body, that of the mother who reunites with her son through an artistic action.

Semíramis González

Querida Victoria o Isabel,

Te escribo esta carta en medio de todos los pasos que estamos dando hasta conocernos. La semana pasada tuve que escuchar casi cien audios contando tu versión de la historia, tu vida y tus procesos de consumos, prostitución y mi propio abandono. En mi performances siempre he intentado mantener la cabeza activa con sentimientos y pensamientos escapando de un aletargamiento o una posible desconexión mental del espacio y del contexto de la obra. Esta carta la escribí ayer para que tú la leas hoy antes de poner tu cuerpo en acción. Poner el cuerpo es algo que llevo haciendo más de treinta años, desde que nací obligado o desde que tú me abandonaste. Durante muchos años te he culpado por abandonarme y he sentido que tú tenías la culpa de todo. Tras escucharte entiendo las circunstancias y creo que tú eres parte y resultado de las mismas exactamente igual que yo. Escucharte hablar de abuso, de prostitución, de violencia sexual y de supervivencia me ha unido más a ti. Durante años daba por hecho que ese era tu discurso, pero no te lo había escuchado a ti directamente. Has sido siempre un fantasma construido en mi cabeza para sobrevivir hasta ahora. Ahora mismo tengo tantas preguntas, que creo que voy a esperar a formular muchas de ellas al día que nos demos la mano por primera vez. La primera pregunta que me viene a la cabeza es el tema del nombre, siempre has sido para Victoria pero ahora eres Isabel. Me gustaría que un día me explicaras bien toda la historia del nombre y esas denuncias con el nombre falso por violación o abuso sexual. Me gustaría en realidad que me explicaras tantas cosas. Aunque he sentido mucha rabia a lo largo de mi vida por el abandono, considero que en este momento de mi vida la rabia se ha rebajado a los menores niveles posibles. Y creo que podré mirarte a los ojos desde la comprensión y la razón. En mi vida he tenido muchas madres y siempre he considerado que ninguna buena. Tú me gestaste en violencia y territorio hostil. No te imaginas el dolor y las lágrimas que he derramado al leer y escucharte en estos pasos como te abusaban y te prostituías conmigo dentro. Luego vino Arancha, que abusó de mi a todo tipo de niveles como intentar venderme, usar mi cuerpo como mercancía y meterme en el mundo de los abusos y maltratos. Y por último Isabel, imagina mi sorpresa al enterarme que tu verdadero nombre era el mismo de mi madre adoptiva. La cual también considero que no fue una buena madre, no estaba preparada en absoluto y considero que vivi una adopción también marcada por el dolor y el maltrato. Tres madres malas o tres malas madres. Y ahora vuelves a mí. Explicándome todo, porque me abandonaste. Te lo volvería a preguntar todos los días de mi vida. ¿Porque me abandonaste? ¿Porque me abandonaste? ¿Porque me abandonaste? Te quiero agradecer el haber decidido exponerte así. El haber sido valiente y contestar a todo. El afrontar todas mis dudas y mis necesidades. El contar tu historia y el exponer de manera valiente tu cuerpo y tu historia. Considero que los dos, de alguna manera, gracias a esto estamos curando. No te voy a engañar, yo sigo muy herido y tengo mucho miedo pero ahora mismo sé más que nunca que nos vamos a conocer en persona. Estoy llorando mientras escribo esta carta. Ya que llevo meses superado. Yo no sé si estos pasos lentos hasta conocernos los he creado como mecanismo de defensa, por necesidad de ir despacio o porque tengo terror a conocernos en persona. Tras más de treinta años de crear obras hablando de tu abandono, de mi heridas y de tu persona estás aquí. En el centro de un museo dispuesta a darlo todo por conocerme, por reparar y por caminar hacia atrás o mejor dicho hacia delante. Yo también voy a dar un paso hacia delante y te ofrezco mi mano.

Nos vemos pronto,

Tu hijo Abel.

The need to search for the maternal figure, through painting, sculpture, and performance, permeates the entire work of Abel Azcona in an overwhelming and profound way. It represents one of the most raw and realistic processes in his entire body of work, while also serving as one of the triggers for his performative base.

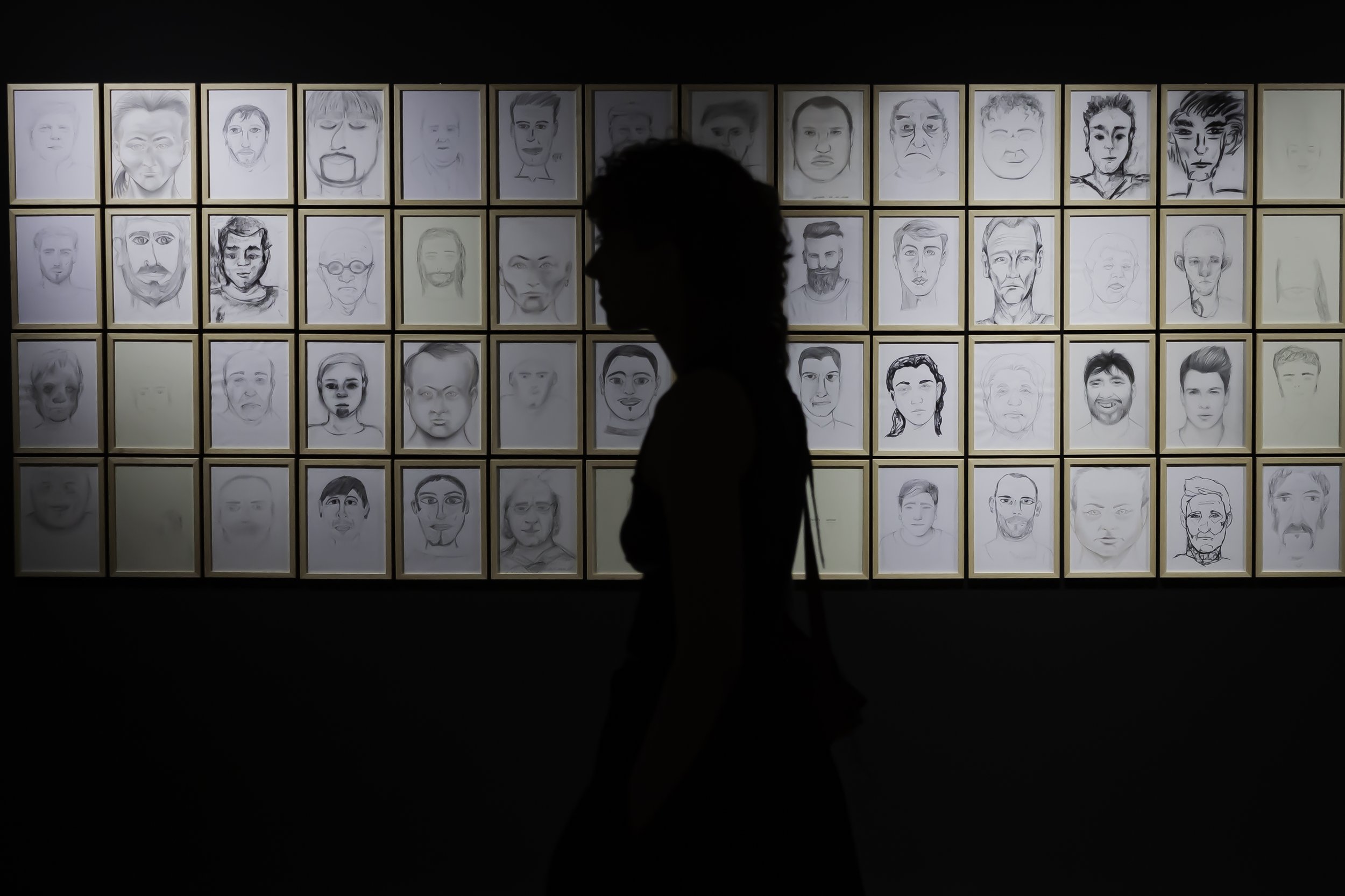

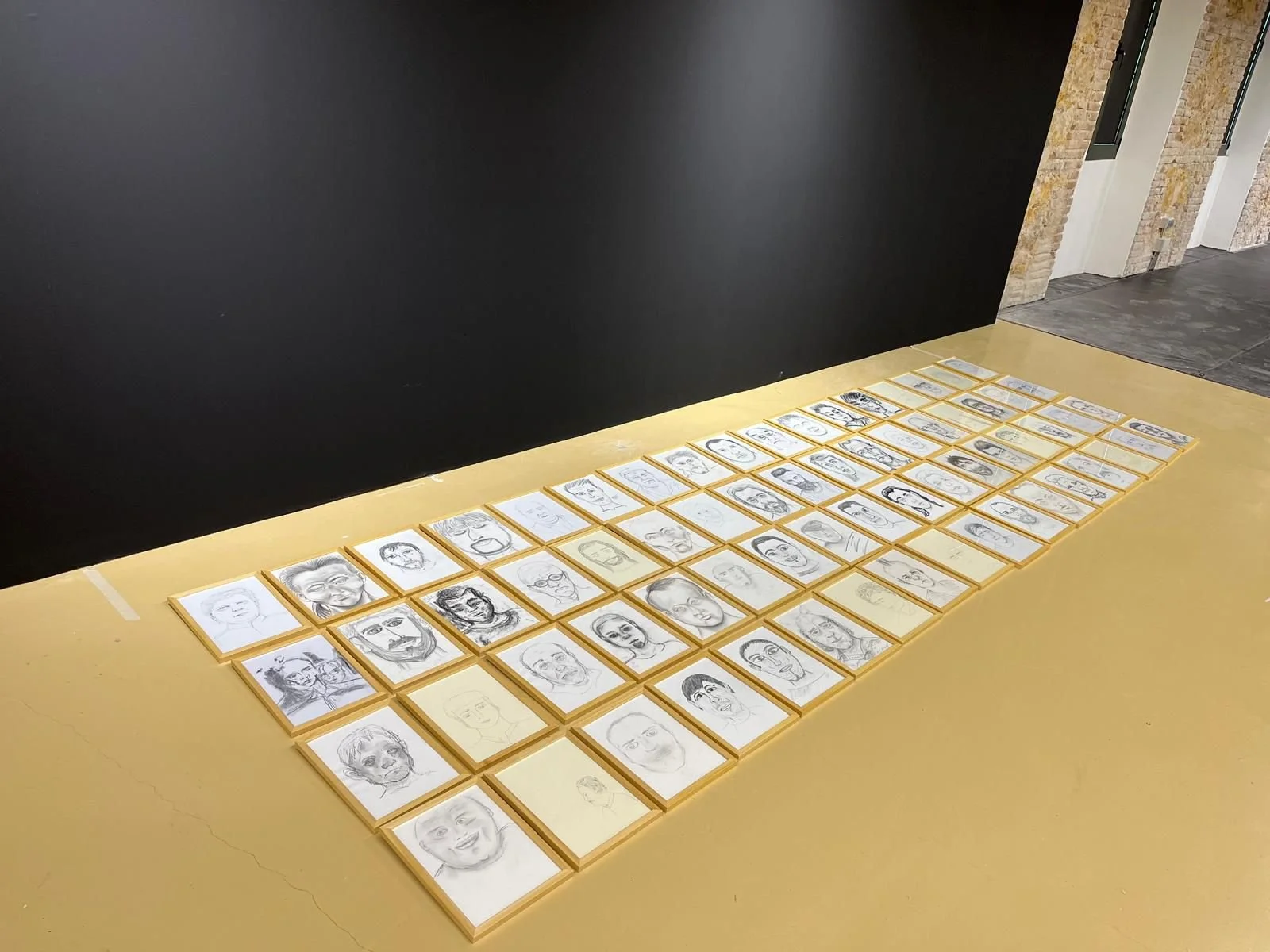

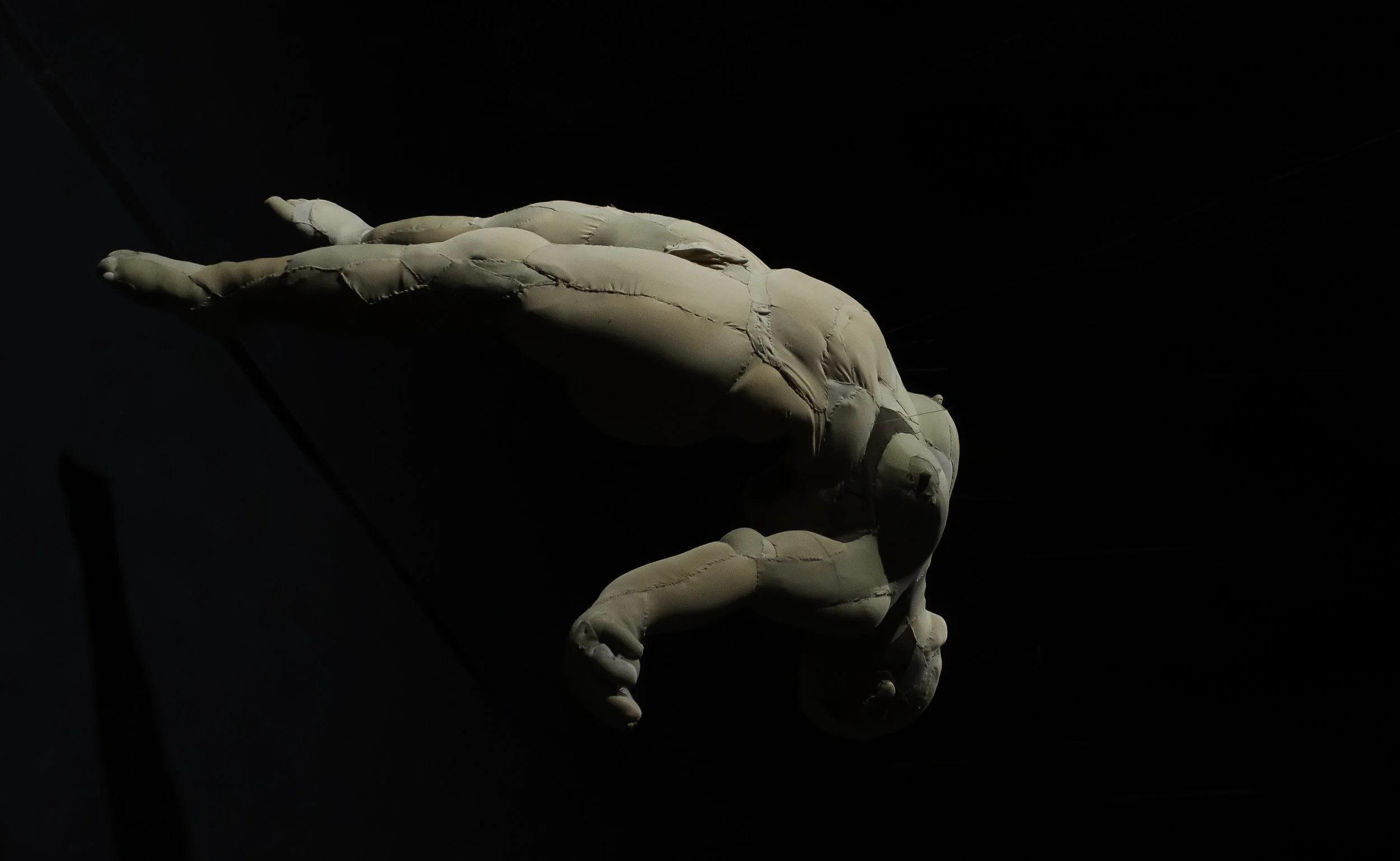

Many of his works have revolved around searching for a mother who abandoned him. From imagining what his mother might be like in "Imaginary Mothers" (Ecuador, Chile, and Spain, 2022-2023), where the artist collectively reflects with people who are motherless, orphaned, or have complex maternal relationships, creating imaginary mothers through portraits, to creating his own mother in "The Soft Mother," 2022-23, where he creates a soft mother to embrace and accompany him, or even choosing his own mother from among Marina Abramović, ORLAN, Tracey Emin, or Yoko Ono in "The Chosen Mothers" (Amsterdam, Paris, 2022-2023), where through photographs, the protagonists assume the roles of mother and child.

This search for the maternal figure concluded in an unexpected way. On November 19th, Abel called me late at night. I didn't answer. The next day, I found out he had located his possible biological mother. Just a few days before the opening of the exhibition "Abel Azcona. My Families 1988-2024" at La Panera, the search had ended.

An exhibition that brought together pieces that traced a complex journey through his family tree, a tree marked by the absence of a mother, but now what? A woman had appeared, claiming to be his mother. Through Manuel Lebrijo, she had found him. She had started following him on social media a few days earlier and had contacted him.

We didn't discuss it any further. We opened the exhibition, and two days later, we resumed the conversation through messages. He told me stories, sent me photos, audio clips... It seemed like everything was falling into place. The only thing missing was a DNA test.

Azcona ultimately decided to embrace this reality and approach it as another performative process, framing it within the six brief actions presented at La Panera. An intimate act in which, through six actions, we transformed the space into a zone for resolving family conflicts. From tattooing the case number on his skin, meeting his sister, reading letters of care, shouting "mama, mama," hugging the soft mother, to finally reaching the mother. This last brief action was intended to be a call to the family mediator from the work "The Search," where Azcona was looking for his biological mother to see if she was still alive, given her severe homelessness and drug addiction, but we eventually replaced it with the reading of the DNA test results that we had requested from a Barcelona laboratory a few days earlier. After sending several couriers to collect the samples, we had the results at La Panera. He held the sealed envelope in his hand. We handed it to Abel, and in front of the attendees, he read them, nervous and broken. It was positive; she was his biological mother.

Azcona closes the chapter on the search for the maternal figure but opens new projects now seeking a connection with his mother—these nine steps toward her.

Azcona's work has a markedly processual nature, often lasting for years. His works don't end in themselves; in fact, many have a trigger that extends them over time.

These triggers sometimes activate collective pieces of catharsis that open a broader discourse, but other times they activate more intimate and individual pieces. This is the case with the closing of the exhibition "My Families 1988-2024" at La Panera, where the last person to visit the exhibition behind closed doors was Isabel Gómez, the mother.

"Meet my mother before you meet me," Abel told me. A round-trip journey to meet Azcona's work before meeting the artist himself. On Sunday, January 28th, we arranged a private visit to the exhibition just for her. For two hours, the mother could walk among the pieces, watch the videos, read all the documents, flip through the albums. Most of the pieces in the exhibition revolved around the maternal figure, and Isabel was able to learn about the story firsthand, confront it and its way of working, and ultimately connect with her son.

ANNA ROIGÉ. Curator and Head of the Documentation Center at the Center for Contemporary Art Creation and Research, La Panera.

After thirty-five years of searching for his mother, attempting to make sense of his own story, the artist Abel Azcona received a call a few months ago from a woman claiming to be his biological mother. Since then, a DNA test, messages, calls, questions, and answers have taken place. In "Born Without a Mother," Abel Azcona will be able to see and hear some of these responses from Isabel, his biological mother, accompanied by attendees, as well as take a step closer towards his mother while preparing for the final reunion scheduled for the end of the year. It is a protest against the omission of the right to not be born, defended on three occasions when the mother attempted to terminate the pregnancy; it is also a defense of abortion as one of the most important measures for protecting childhood. It is a journey through autobiographical violence and at the same time through systemic violence that conditions and triggers these events; it is a quest for the original violence. It is a political artifact.

Nerea Campo

La búsqueda constante de Abel Azcona de su propia identidad, atravesada por violencias como el abuso infantil, el abandono o la alienación, a la par que le han posicionado como una figura masculina defensora del aborto, de los derechos de las mujeres y contra la violencia, precisamente a partir de su propia historia. Por otro lado, la de la madre, cuyo relato es atravesado por la vulnerabilidad de la adicción a las drogas, el verse obligada a prostituirse, posteriormente abandonar a su hijo, o las agresiones sexuales. Su relato es el de la vulnerabilidad de las mujeres que sufren violencia sólo por el hecho de serlo, aquí concretado en un cuerpo concreto, el de la madre que se reencuentra con su hijo a través de una acción artística.

Semiramis Gonzalez

Querida Victoria o Isabel,

Te escribo esta carta en medio de todos los pasos que estamos dando hasta conocernos. La semana pasada tuve que escuchar casi cien audios contando tu versión de la historia, tu vida y tus procesos de consumos, prostitución y mi propio abandono. En mi performances siempre he intentado mantener la cabeza activa con sentimientos y pensamientos escapando de un aletargamiento o una posible desconexión mental del espacio y del contexto de la obra. Esta carta la escribí ayer para que tú la leas hoy antes de poner tu cuerpo en acción. Poner el cuerpo es algo que llevo haciendo más de treinta años, desde que nací obligado o desde que tú me abandonaste. Durante muchos años te he culpado por abandonarme y he sentido que tú tenías la culpa de todo. Tras escucharte entiendo las circunstancias y creo que tú eres parte y resultado de las mismas exactamente igual que yo. Escucharte hablar de abuso, de prostitución, de violencia sexual y de supervivencia me ha unido más a ti. Durante años daba por hecho que ese era tu discurso, pero no te lo había escuchado a ti directamente. Has sido siempre un fantasma construido en mi cabeza para sobrevivir hasta ahora. Ahora mismo tengo tantas preguntas, que creo que voy a esperar a formular muchas de ellas al día que nos demos la mano por primera vez. La primera pregunta que me viene a la cabeza es el tema del nombre, siempre has sido para Victoria pero ahora eres Isabel. Me gustaría que un día me explicaras bien toda la historia del nombre y esas denuncias con el nombre falso por violación o abuso sexual. Me gustaría en realidad que me explicaras tantas cosas. Aunque he sentido mucha rabia a lo largo de mi vida por el abandono, considero que en este momento de mi vida la rabia se ha rebajado a los menores niveles posibles. Y creo que podré mirarte a los ojos desde la comprensión y la razón. En mi vida he tenido muchas madres y siempre he considerado que ninguna buena. Tú me gestaste en violencia y territorio hostil. No te imaginas el dolor y las lágrimas que he derramado al leer y escucharte en estos pasos como te abusaban y te prostituías conmigo dentro. Luego vino Arancha, que abusó de mi a todo tipo de niveles como intentar venderme, usar mi cuerpo como mercancía y meterme en el mundo de los abusos y maltratos. Y por último Isabel, imagina mi sorpresa al enterarme que tu verdadero nombre era el mismo de mi madre adoptiva. La cual también considero que no fue una buena madre, no estaba preparada en absoluto y considero que vivi una adopción también marcada por el dolor y el maltrato. Tres madres malas o tres malas madres. Y ahora vuelves a mí. Explicándome todo, porque me abandonaste. Te lo volvería a preguntar todos los días de mi vida. ¿Porque me abandonaste? ¿Porque me abandonaste? ¿Porque me abandonaste? Te quiero agradecer el haber decidido exponerte así. El haber sido valiente y contestar a todo. El afrontar todas mis dudas y mis necesidades. El contar tu historia y el exponer de manera valiente tu cuerpo y tu historia. Considero que los dos, de alguna manera, gracias a esto estamos curando. No te voy a engañar, yo sigo muy herido y tengo mucho miedo pero ahora mismo sé más que nunca que nos vamos a conocer en persona. Estoy llorando mientras escribo esta carta. Ya que llevo meses superado. Yo no sé si estos pasos lentos hasta conocernos los he creado como mecanismo de defensa, por necesidad de ir despacio o porque tengo terror a conocernos en persona. Tras más de treinta años de crear obras hablando de tu abandono, de mi heridas y de tu persona estás aquí. En el centro de un museo dispuesta a darlo todo por conocerme, por reparar y por caminar hacia atrás o mejor dicho hacia delante. Yo también voy a dar un paso hacia delante y te ofrezco mi mano.

Nos vemos pronto,

Tu hijo Abel.

La necesidad de la búsqueda de la figura materna, desde lo pictórico, lo escultórico, pasando por lo performativo atraviesa toda la obra de Abel Azcona de una manera abrumadora y profunda. Supone uno de los procesos más crudos y realistas de toda su obra y a la vez ha sido uno de los detonantes de su base performativa.

Muchos de sus trabajos han consistido en buscar a una madre que le abandonó. Desde imaginar cómo sería su madre en Las madres imaginarias (Ecuador, Chile y España, 2022-2023) donde el artista reflexiona de forma colectiva con personas sin madre, huérfanos o con maternidades complejas, como seria su madre imaginaria y lo materializan mediante retratos, hasta construirse su propia madre en La madre blanda, 2022-23, donde se construye una madre blanda a la que poder abrazar y que le pueda acompañar, o incluso elegir a su propia madre entre Marina Abramović, ORLAN, Tracey Emin o Yoko Ono en Las madres elegidas (Amsterdam, Paris, 2022-2023) donde mediante fotografías los protagonistas asumen los roles de madre hijo.

Esta búsqueda de la figura materna concluyó de manera inesperada. El 19 de noviembre Abel me llamó a altas horas de la noche. No respondí. El día siguiente supe que había encontrado a su posible madre biológica. A pocos días de la inauguración de la exposición Abel Azcona. Mis familias 1988-2024. en La Panera, la búsqueda había terminado.

Una muestra que reunía piezas que nos marcaban un recorrido complejo a través de su árbol genealógico, un árbol marcado por la ausencia de la madre, pero ¿y ahora qué? Ha aparecido una mujer que dice ser su madre. A través de Manuel Lebrijo ella lo había localizado. Ya hacía unos días que había empezado a seguirle en redes sociales y a contactar con él.

No hablamos más del tema. Inauguramos la exposición y pasados dos días, retomamos el tema por mensajes. Me contó historias, me mandó fotos, audios… parecía que todo iba encajando. Solo faltaba la prueba de ADN.

Azcona finalmente decidió asumir este hecho, esta realidad y afrontarla como un proceso performativo más y enmarcarlo dentro de las 6 acciones breves presentadas en La Panera. Un acto íntimo en el que mediante 6 acciones convertimos el espacio en una zona de resolución de conflictos familiares. Des de tatuarse el número de su expediente, conocer a su hermana, leer las cartas de los cuidados, gritar mama mama, abrazar a la madre blanda, hasta llegar a la madre. Esta última acción breve tenía que ser una llamada al mediador familiar protagonista de la obra la “La búsqueda” donde Azcona buscaba a su madre biológica para comprobar si ella ya había fallecido o no, debido a su situación grave de calle y drogodependencia, pero finalmente la sustituimos por la lectura de los resultados de las pruebas de ADN que unos días antes habíamos solicitado en un laboratorio de Barcelona. Después de mandar varios mensajeros para hacer las muestras, teníamos los resultados en La Panera. Los tenía en un sobre cerrado en la mano. Lo entregamos a Abel y frente a los asistentes los leyó, nervioso y roto. Era positivo, es su madre biológica.

Azcona cierra la etapa de la búsqueda de la figura materna, pero abre nuevos proyectos buscando ahora un acercamiento hacia la madre, estos nueve pasos hacia ella.

El trabajo de Azcona tiene un marcado carácter procesual, muchas veces con años de duración. Sus obras no se detienen en sí mismas, de hecho, muchas de ellas tienen un detonante que hace que se prolonguen en el tiempo.

Estos detonantes sirven para activar en ocasiones, piezas colectivas de catarsis que abren un discurso en torno a una temática completa, pero en otras ocasiones activan piezas más íntimas y de carácter individual. Es el caso del cierre de la exposición Mis familias 1988-2024 en La Panera, donde la última persona que visitó la exposición a puerta cerrada fue Isabel Gómez, la madre.

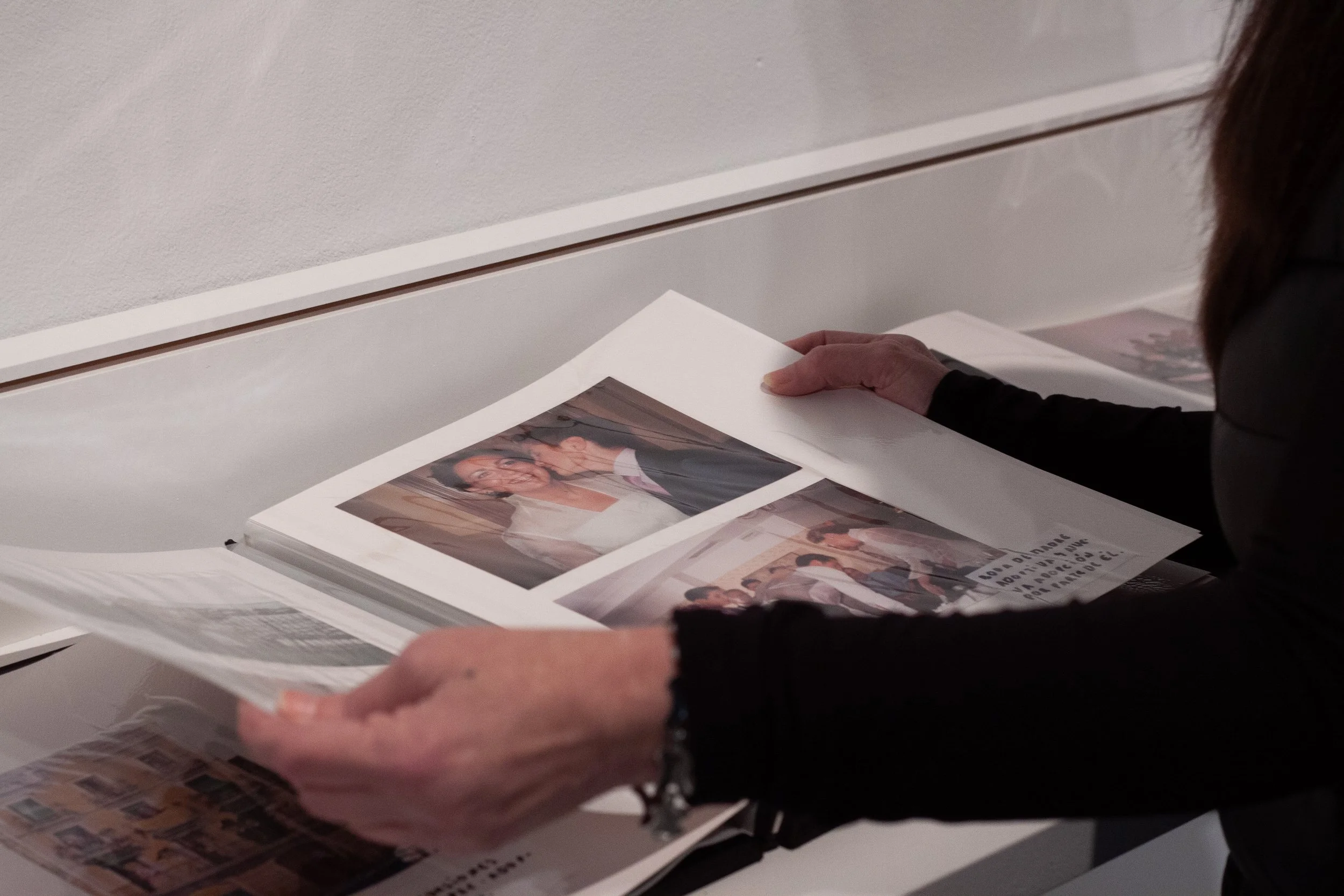

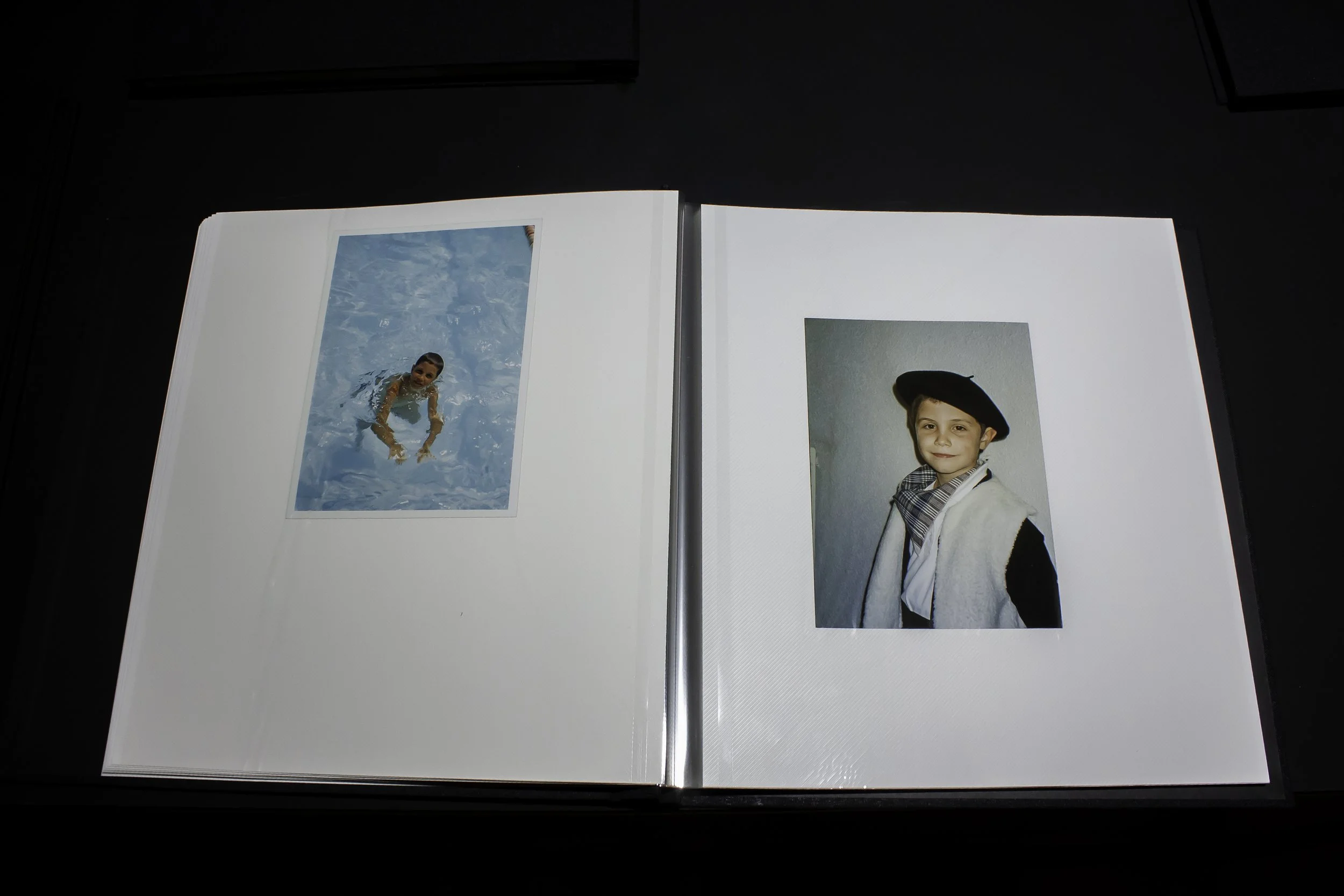

«Conocerás mi madre antes que yo me dijo Abel.» Un viaje de ida y vuelta para conocer en persona la obra de Azcona, antes que al propio artista. El domingo 28 de enero le pudimos hacer una visita a la muestra solo para ella. Durante dos horas la madre pudo pasear entre las piezas, ver los videos, leer todos los documentos, hojear los álbumes. La mayoría de las piezas en la exposición giraban en torno a la figura materna e Isabel pudo conocer la historia en primera persona, enfrentarse a ella y a su forma de trabajar y en definitiva acercarse a su hijo.

ANNA ROIGÉ. Comisaria y Responsable del Centro de Documentación del Centro de Creación e Investigación en Artes Contemporáneas La Panera.

Después de treinta y cinco años de búsqueda de la madre, de intentos de hacer inteligible su propia historia, el artista Abel Azcona recibe hace unos meses la llamada de una mujer que dice ser su madre biológica. Desde entonces, una prueba de ADN, mensajes, llamadas, preguntas y respuestas han tenido lugar. En "Nacer sin madre", Abel Azcona podrá ver y escuchar algunas de estas respuestas de Isabel, su madre biológica, acompañado de los asistentes, así como dar un paso más de acercamiento hacia la madre mientras ensaya el reencuentro final que tendrá lugar a finales de año. Es una denuncia a la omisión del derecho a no nacer, defendido en tres ocasiones en las que la madre intenta interrumpir el embarazo; también es una defensa del aborto como una de las medidas más importantes de protección a la infancia. Es un recorrido por la violencia autobiográfica y al mismo tiempo por la violencia sistémica que condiciona y desencadena estos eventos, es una búsqueda de la violencia original. Es un artefacto político.

Nerea Campo

THE FIRST STEP was activated on October 20, 2023, with an instant message from Isabel Gómez Aranda to the artist Abel Azcona. She obtained the artist's contact through Manuel Lebrijo, who is listed as Azcona's biological father without actually being so. Lebrijo had not been in contact with Azcona since the performance "Volver al Padre" (Return to the Father).

EL PRIMER PASO se activó el 20 de octubre de 2023 con un mensaje instantáneo de Isabel Gómez Aranda al artista Abel Azcona. Ella consiguió el contacto de el artista a través de Manuel Lebrijo, que consta como padre biológico de Azcona sin serlo. Lebrijo no mantenía contacto con Azcona desde la performance Volver al Padre.

It's very hard for me to speak too, because right now I'm devastated. It's very hard for me to speak, it's extremely hard for me to speak. I don't even know what to say to you. I'm completely overwhelmed.

For me, I'll be completely honest with you, that in some way, both my work and life have been based on your absence, and so it happens that I'm a bit in disbelief. Also, I had you with a completely different name and surname, so right now I don't know what to do.

It's normal that you're in disbelief; and about the name and surname, I never gave my name or surname because at that time, before giving birth to you, I was a minor and never gave my real name or surname. My life has always been a lie; now is when my life is true, but my life has always been a lie, really, and you don't know how badly I've had it because of the lie I've always lived. Now, for a few years now, my life is stable and I'm a new person, but my life has always been a mess, a lie; I've ruined lives and I've even ruined my own life.

You can start telling me things, but little by little without getting overwhelmed. I'm totally open, I've worked a lot in therapies and everything, and I'm not going to be scared by anything at all. So, you can tell me everything you want to tell me. You can tell me calmly and without getting overwhelmed because I'm not going to judge you. And if later you think I should judge, we'll come to an agreement.

Okay, I've always looked for you with those names and surnames. In fact, on my birth certificate and all my childhood papers, you appear as Vicky or Victoria Lujan Gutiérrez and so on. And once I searched and found someone who was in Santander with a thing about a fine and thought, seven or eight years ago, I thought it was you. But of course, I don't know if there’s another person with that name. Okay, tell me a bit. If you don't want to tell me about the past, tell me about the present. Do you work? Do you live in Valencia? No, you live in Málaga, you told me, right? Or are you from Valencia?

No, I don't work. I live in Málaga, I have a non-contributory pension and I live off that. I live in a little apartment here, in Málaga capital, and I don't work. I don't work because I'm a bit disabled; the life I've led gave me a stroke on the right side of my body and I was in a center for many years. Now it's been two years that I'm fine, that I recovered from the stroke and now I'm fine. I live alone in an apartment that they found for me there, at Caritas center, and I live here. I pay for electricity, I pay for water and with the 400 euros I earn, I live and that's it. I do crafts, I do things, I'm a volunteer, I go to Caritas here from time to time to lend a hand where they call me. And I go to the center every fifteen days to see my former companions and the people who helped me get ahead because I arrived devastated, I arrived with a stroke and I arrived... well, in bad shape and there I recovered. I spent about 6 years in the center. After the hospital, they took me by ambulance to the center. I was bedridden for a long time, they fed me, washed me, dressed me, and did everything for me. I spent a time in bed, then in a wheelchair, then with a walker, finally with a cane. Now it's been two years that I'm independent, that I take care of myself and do everything myself. But I was very bad. I don't know, I can say I've paid, I've paid and I'm paying, right? For all the damage I caused myself, because I caused it, of course, I can't blame anyone for that. The blame is mine, I took the bad path and I have to face the consequences, right? And that's what I've paid and I'm paying for, but well, now I feel good because I'm active, I do things, I like crafts. Now I'm studying because when I was a child I could never get my ESO and now I'm getting it. I go to classes on Mondays and Wednesdays and I'm studying everything I didn't do as a kid, I'm doing it now. But well, it's never too late if happiness is good, right? And well, I don't know, it's just that suddenly I don't know the truth, it's very hard for me to tell you. Ask me things and I can answer them.

Here at the center, I also had a psychologist and I still have her, I see her every fifteen days because she still works at the center. She is an educator and psychologist, and while I lived there, she was always my psychologist and she still is. Everything I live and everything I've done, I usually tell her, I usually tell her my day-to-day life and my things and everything. And well, she is always there to listen to me. I haven't told her about you because I didn't want to tell her, but well, one day I will tell her, but for now, I haven't told her anything. She knows I had a son and that I don't know anything about him and that's it, but she doesn't know anything more.

And tell me, how did you find me? Did you write to Manolo a week ago? How long ago? Did you ask him for my contact? Did he tell you my name? Because of course, the name Abel was told to me that it was the name you had given me at the clinic, because they told you to give me a name, and you named me Abel. And David was given to me later, by grandma María and the Lebrijo, but when you gave birth to me, I was called Abel first and for that reason, I later removed David because I didn't like it because it was given to me by the Lebrijo. Sorry, I'm slow to answer you, but I'm digesting everything and this is complex, eh?

Me too, me too, it's killing me to talk to you. I have a lump in my throat that's making it very hard for me, but don't worry, you don't have to... I understand, I understand. When things are done wrong, you have these consequences, that I've done everything wrong from the beginning. So, I know, I know that everything that happens to me is little, and everything bad I've lived through is little compared to what I really deserved. And I don't know the truth, I'm devastated right now.

I contacted Manuel to see if he knew anything about you because I really tried to find you but didn't know with what surname or what to look for. But well, that, and I was able to get in touch with him and asked him about you. So, yesterday we had a pretty long conversation of messages until he told me who you were, where I could find you, and gave me the name to look for you and I searched for you and read everything you have on your wall and so on.

You were very handsome and you are! You are very handsome, not were, are. The last time I saw you, you were four years old because I went to Pamplona, I went and found out where Manuel and Arantza lived. I went to their house and saw you when you were four years old, that was the last time I saw you. I never saw you again, that was the last time I saw you, when you were four and you were very handsome, you had long hair.

With what you tell me, the truth is that everything fits because I had this story, but I had three, but you did go to the apartment and tried to see me, and I was playing with Arantza and Manolo, and I knew that. So yes, it fits, the truth. The only thing that has really thrown me off is the name, because we always called you Vicky. Vicky, Manolo always called you Vicky, Vicky. Everyone always Vicky and on my birth certificate you appear as Vicky Luján Gutiérrez. And not long ago, I found a Vicky Luján Gutiérrez who had been in Santander, so I didn't understand the name very well, what threw me off the most. Everything else fits. I also tell you that I did a search for origins and found a woman named Victoria Luján who was in a precarious situation on the street many years ago, ten or twelve years ago. And we had a meeting, but she didn't want to know me, but I assumed that woman was my mother. But I never searched again and assumed she was even dead because she was a woman in a situation of drug addiction, heroin, but apparently, it wasn't you, it must have been another Victoria Luján because your name wasn't correct.

I invented that name as a minor, I invented it because I escaped from the reformatory as a minor and invented that name. And then, after years, once the police caught me and since I used that name in complaints so they wouldn't take me back to the reformatory, once they stopped me and detained me believing I was Victoria Luján Gutiérrez because apparently, that woman had problems too, and they detained me and kept me for seventy-two hours. Then they released me, but I invented that name, thinking it didn't exist, and then it did exist. There was a person because I remember being detained with that name because she was wanted, and after seventy-two hours, they released me. But I invented the name and then it coincidentally existed, that person existed.

A mi me cuesta mucho hablar también, porque yo ahora mismo estoy destrozada. A mi me cuesta mucho hablar, a mi me cuesta muchísimo hablar. No sé ni que decirte. Estoy totalmente pillada.

A mi me pasa, te voy a ser totalmente sincero, que de alguna manera, tanto mi trabajo como vida la he fundamentado en tu ausencia y entonces me pasa que estoy un poco entre incrédulo, además yo te tenía con un nombre y unos apellidos, un nombre y unos apellidos totalmente diferentes, entonces ahora mismo yo no sé que hacer.

Es normal que estés incrédulo; y lo del nombre y los apellidos, yo nunca di mi nombre ni mis apellidos porque cuando yo estaba en ese tiempo, antes de darte a luz, era menor de edad y nunca di mi nombre verdadero ni mis apellidos. Es que mi vida ha sido siempre una mentira; ahora es cuando mi vida es una verdad, pero mi vida ha sido siempre una mentira, de verdad, y tú no sabes lo mal que yo lo he pasado por la mentira que he vivido siempre. Ahora, de unos pocos años para acá, es cuando de verdad mi vida está estable y soy una nueva persona, pero mi vida ha sido siempre un asco, una mentira; he destrozado vidas y me he destrozado hasta mi propia vida.

Me puedes ir contando cosas, pero poco a poco sin que te agobies. Yo estoy totalmente abierto, he trabajado muchísimo en terapias y de todo, y no me voy a asustar absolutamente por nada. Entonces, me puedes contar todo lo que quieras contarme. Me lo puedes contar con tranquilidad y eso, sin agobiarte porque yo no te voy a juzgar. Y si luego dices que crees que tengo que juzgar, pues ya llegaremos a un acuerdo.

Vale, yo siempre te he buscado con esos nombres y esos apellidos. De hecho, en mi partida de nacimiento y en todos los papeles de mi infancia sales como Vicky o como Victoria Lujan Gutiérrez y eso. Y una vez busqué y encontré una que estaba como en Santander con una cosa de una multa y pensaba, hace siete u ocho años, pensaba que eras tú. Pero claro, no sé si habrá otra persona que se llame así. Vale, cuéntame un poco. Si no me quieres contar del pasado, cuéntame del presente. ¿Trabajas? ¿Vives en Valencia? No, vives en Málaga, me has dicho ¿No? o que eres de Valencia.

No, no trabajo. Vivo en Málaga, tengo una pensión no contributiva y vivo de eso. Vivo en un pisito aquí, en Málaga capital, y no trabajo. No trabajo porque estoy un poco discapacitada; la vida que he llevado me dio un ictus en la parte derecha del cuerpo y estuve en un centro muchos años. Ahora llevo dos años que ya estoy bien, que ya me recuperé del ictus y ya estoy bien. Vivo sola en un piso que me buscaron ahí, en el centro de Cáritas, y aquí vivo. Pago la luz, pago el agua y con los 400 euros que cobro, pues vivo y aquí estoy. Hago manualidades, hago cosas, soy voluntaria, voy aquí a Cáritas de vez en cuando a echar una mano donde me llaman. Y aquí al centro solo voy cada quince días a ver a mis antiguos compañeros y compañeras y a la gente que me ayudó a salir adelante, porque yo llegué destrozada, llegué con un ictus y llegué... pues hecha polvo y ahí me recuperé. Estuve cerca de 6 años en el centro. Después del hospital me llevaron en ambulancia al centro. Estuve en cama mucho tiempo, me daban de comer, me lavaban, me vestían y me hacían todo. Estuve un tiempo en la cama, luego en silla de ruedas, después en andador, por último un bastón. Ahora llevo dos años aquí, que llevo independiente, que ya me valgo por mí misma y ya hago todo yo. Pero yo estaba muy mal. Yo no sé, puedo decir que he pagado, he pagado y estoy pagando, ¿no? Todo el daño que me busqué, porque me lo busqué claro, de eso no puedo culpar a nadie. La culpa es de una, la mala vida la cogió una y una tiene que asumir las consecuencias, ¿no? Y eso es lo que he pagado y estoy pagando, pero bueno, ahora me siento bien porque estoy activa, hago cosas, me gustan las manualidades. Ahora estoy estudiando porque cuando era niña no me pude sacar nunca la ESO y ahora me la estoy sacando. Voy los lunes y los miércoles a clases y estoy estudiando todo lo que no hice de chica, lo estoy haciendo ahora. Pero bueno, nunca es tarde si la dicha es buena, ¿no? Y bueno, no sé, es que así de golpe no sé la verdad, es que me cuesta mucho contarte. Pregúntame cosas y yo te las puedo responder.

Aquí en el centro he tenido también una psicóloga y la sigo teniendo, que la veo cada quince días, porque ella trabaja ahí en el centro todavía. Ella es educadora y psicóloga, y mientras yo vivía ahí, pues ha sido siempre mi psicóloga y sigue siendo mi psicóloga. Todo lo que vivo y todo lo que he hecho, pues se lo suelo contar, le suelo contar mi día a día y mis cosas y todo. Y bueno, ella está ahí siempre para escucharme. De ti, no le he hablado, porque tampoco... tampoco quería contarle, pero bueno, un día ya le contaré, pero de momento no le he contado nada. Ella sabe que tuve un hijo y que no sé nada de él y ya está, pero no sabe nada más.

Y cuéntame, ¿Cómo has llegado a mí? Has escrito a Manolo ¿Hace una semana? ¿Hace cuánto? ¿Le has pedido mi contacto? ¿Te ha dicho mi nombre? Porque claro, el nombre de Abel a mí me dijeron que es el nombre que me has puesto vosotros en la clínica, porque os dijeron que me has de poner un nombre, y el de Abel me pusisteis. Y David me lo pusieron después, la abuela María y los Lebrijo, pero yo, cuando tú me diste a luz, me llamaba primero Abel y por ese motivo luego me quité el David, porque el David no me gustaba, porque me lo habían puesto los Lebrijo. Perdona que tarde en contestarte, pero estoy digiriendo todo y esto es complejo, ¿eh?

Yo también, yo también, esto me está costando la vida el hablar contigo. Tengo un nudo en la garganta que me está costando una vida, pero tranquilo, tampoco me tienes... yo te entiendo, te entiendo. Cuando las cosas se hacen mal, uno tiene estas consecuencias, que yo que he hecho todo mal desde un principio. Entonces, yo sé, yo sé que todo lo que me pasa es poco y todo lo que he vivido, malo, es poco a lo que realmente yo me merecía. Y yo no sé la verdad, estoy hecha polvo ahora mismo.

Yo me puse en contacto con Manuel por si sabía algo de ti, porque realmente yo te he intentado buscar, pero no sabía con qué apellido ni con qué buscarte. Pero bueno, eso, y me pude poner en contacto con él y le pregunté por ti. Entonces, ayer tuvimos una conversación bastante larga de mensajes hasta que me dijo quién eras, dónde te podía encontrar y me dio el nombre para buscarte y yo te busqué y leí todo lo que tienes en tu muro y eso.

Eras muy guapo y eres ¡Eres! muy guapo, no eras, eres. La última vez que te vi tenías cuatro años, porque fui a Pamplona, fui y me enteré dónde vivía Manuel y Arantza. Fui a su casa y te vi con cuatro años, fue la última vez que te vi. Ya no te vi nunca más, esa fue la última vez que te vi, con cuatro años y estabas guapísimo, tenías melenita.

Con esto que me cuentas, la verdad que me encaja todo, porque esta historia yo tenía tres, pero sí que fuiste al piso y me intentaste ver y yo estaba jugando con Arantza y con Manolo, y esto lo sabía yo. Así que sí que me encaja, la verdad. Lo único que sí me ha descolocado muchísimo es lo del nombre, porque a ti siempre te hemos llamado Vicky. Vicky, Manolo siempre te llamaba Vicky, Vicky. Todo el mundo siempre Vicky y en mi partida de nacimiento sales Vicky Luján Gutiérrez. Y yo encontré hace no mucho a una Vicky Luján Gutiérrez que había estado en Santander, entonces no entendía muy bien lo del nombre, lo que más me descuadra a mí. Todo lo demás me encaja. También te digo que yo hice una búsqueda de orígenes y encontré a una mujer que se llamaba Victoria Luján que estaba en situación de precariedad en la calle hace muchos años, hace diez o doce años. Y tuvimos un encuentro, pero ella no me quiso conocer, pero yo di por hecho que esa mujer era mi madre. Pero ya nunca más busqué y ya daba por hecho que ya hasta estaba muerta, porque era una mujer en situación de drogadicción, heroína pero, por lo visto no eras tú, será otra Victoria Luján porque tu nombre no era el correcto.

Yo me inventé ese nombre siendo menor, me lo inventé porque yo me escapé del reformatorio siendo menor y me inventé ese nombre. Y después, al cabo de los años, una vez me cogió la policía y como yo ponía ese nombre en denuncia para que no me llevaran al reformatorio, pues una vez me pararon y me detuvieron creyendo que era Victoria Luján Gutiérrez, que por lo visto esa mujer había tenido problemas también, y me detuvieron y me tuvieron setenta y dos horas detenida. Después me soltaron, pero ese nombre me lo inventé yo, creyendo que no existía y después sí existía. Existía una persona porque recuerdo que me detuvieron con ese nombre, porque estaba en busca y captura y a las setenta y dos horas, pues me soltaron. Pero yo me inventé el nombre y luego dio la coincidencia de que existía, de que esa persona existía.

Twelve days before inaugurating the exhibition "ABEL AZCONA. MIS FAMILIAS 1988-2024," a potential biological mother contacted the artist, expressing a desire to effectively return to his life. After setting aside the matter for over a month, Azcona decides to address it within the framework of the exhibition, making the sixth action the reading of the DNA test requested days earlier at a laboratory in Barcelona, mutually agreed upon. After breaking into tears and reading the result, the artist himself called the person who, according to the positive outcome, is his biological mother. He would have called her even if the result had been negative.

"For over a month, I refused to think about the situation that, after thirty-five years of searching, suddenly my possible biological mother would come knocking. I had to force myself to confront the situation in front of the visitors to read the document and accept that all of it was reality."

The action showed us a nervous and shattered Azcona until the positive resolution of the test, where he called live and sent several voice messages to the person who, according to the laboratories with a 99.94% certainty, is his biological mother.

Doce días antes de inaugurar la muestra ABEL AZCONA. MIS FAMILIAS 1988-2024 una posible madre biológica contactó con el artista queriendo volver de manera efectiva a su vida. Tras dejar arrinconar el asunto durante más de un mes, Azcona decide asumirlo en el marco de la muestra y que la sexta acción sea la lectura de la prueba de ADN solicitada días antes en un laboratorio de Barcelona de manera mutua. Tras romper a llorar y la lectura del resultado, el propio artista llamó a la que según el resultado positivo es su madre biológica. También le hubiera llamado si el resultado hubiera resultado negativo.

«Durante más de un mes rehuse a pensar sobre la situación de que tras treinta y cinco años de búsqueda de repente mi posible madre biológica llamara a la puerta. Tuve que obligarme a enfrentar la situación frente a los visitantes para leer el documento y asumir que todo aquello era realidad.»

La acción nos mostró un Azcona nervioso y roto hasta la resolución positiva de la prueba donde llamó en directo y envió varios audios a la que, según los laboratorios al 99,94 %, es su madre biológica.

"Azcona calling his biological mother to announce to her that the result was positive. / Azcona llamando a su madre biológica para anunciarle que el resultado era positivo.

THE SECOND STEP involved commissioning a DNA test at a laboratory in Barcelona in November 2023. The result was received at the La Panera Art Center to carry out a live performance. The reading took place in front of a hundred people for the first time.

EL SEGUNDO PASO consistió en encargar en noviembre de 2023 una prueba de Adn en un laboratorio de Barcelona. El resultado fue recibido en el Centro de Arte La Panera para realizar una performance en vivo. La lectura se realizó frente a cien personas por primera vez.

Azcona with the envelope of the laboratory results. / Azcona con el sobre de los resultados del laboratorio.

Prueba de Adn final. Documento resuelto durante la performance en el Centro de Arte La Panera.

In collaboration with the Marina Abramovic Institute, Abel Azcona, alongside Marina Abramović and other artists, held a culminating event at Amsterdam's Carré Theater. This farewell gathering was pivotal, marking the closure of a series of performances centered on Azcona's reconciliation with his mother's death. She had endured a life marred by homelessness, substance abuse, and prostitution. The pieces showcased pushed Azcona to the brink as he mirrored his mother’s struggles through acts of self-prostitution, drug use, and ultimately, acceptance and farewell in a poignant third video.

The final presentation left the audience in a profound state of shock. During this event, Azcona revealed his next step would involve seeking out a family mediator to ascertain his mother’s fate, her precarious existence having left her whereabouts and condition unknown.

After returning from this intense series in Amsterdam, Azcona chose to delay his next exhibition at the La Panera Art Center, which would delve into themes surrounding his family. He deemed it the ideal venue for a live performance that would involve making the pivotal call to confirm his mother’s status.

However, just days before the exhibition's opening, an unexpected turn of events unfolded as Azcona's biological mother appeared in person, rendering the planned performance unnecessary. Instead, the event evolved into a live DNA test performed with his newly reconnected mother. This unexpected reunion not only nullified the need for the original performance but also forged a powerful and symbolic link between the farewell actions in Amsterdam and the revelatory encounter at the exhibit.

Paula Garcia, Marina Abramović Institute

En colaboración con el Instituto Marina Abramovic, Abel Azcona, junto con Marina Abramović y otros artistas, llevaron a cabo un evento culminante en el Teatro Carré de Ámsterdam. Esta reunión de despedida fue fundamental, marcando el cierre de una serie de actuaciones centradas en la reconciliación de Azcona con la muerte de su madre. Ella había soportado una vida plagada de indigencia, abuso de sustancias y prostitución. Las piezas presentadas llevaron a Azcona al límite mientras reflejaba las luchas de su madre a través de actos de autoprost*tución, uso de drogas y, finalmente, aceptación y despedida en un tercer video conmovedor.

La presentación final dejó a la audiencia en un estado de conmoción profunda. Durante este evento, Azcona reveló que su siguiente paso sería buscar a un mediador familiar para averiguar el destino de su madre, cuya existencia precaria había dejado su paradero y condición desconocidos.

Después de regresar de esta intensa serie en Ámsterdam, Azcona decidió retrasar su próxima exposición en el Centro de Arte La Panera, que exploraría temas relacionados con su familia. Consideró que sería el lugar ideal para una performance en vivo que involucraría realizar la llamada crucial para confirmar el estado de su madre o su posible muerte.

Sin embargo, solo unos días antes de la inauguración de la exposición, ocurrió un giro inesperado cuando la madre biológica de Azcona apareció en persona, haciendo innecesaria la actuación planeada. En cambio, el evento evolucionó hacia una prueba de ADN en vivo realizada con su recién reconectada madre. Este reencuentro inesperado no solo anuló la necesidad de la performance original, sino que también forjó un vínculo poderoso y simbólico entre las acciones de despedida en Ámsterdam y el encuentro revelador en la exposición.

Paula Garcia, Marina Abramović Institute

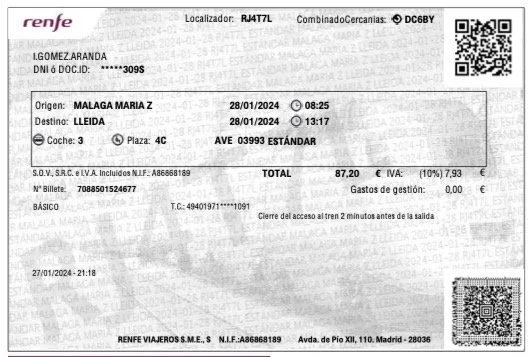

THE THIRD STEP unfolded through a travel performance on January 28, 2024. The performance served as the closing event for the Abel Azcona exhibition "My Families 1988-2024" at the La Panera Art Center in Lleida. It also marked the first encounter of Abel Azcona's biological mother with the artist's work, as she had not met Azcona in person before. Earlier in the exhibition, Azcona had conducted a performance where the results of a DNA test were revealed. Given the positive outcome of the clinical sample, it made sense to invite his mother to the closing performance. On a round-trip journey throughout the day, Isabel Gómez Aranda traveled from Málaga to Lleida. She participated in a guided tour and attended the closing of the exhibition by the museum team. For over an hour, the mother interacted performatively with the exhibition installations, read about all the processes, viewed video pieces, and approached Azcona's work related to family. Most of the exhibited pieces had a direct connection to the maternal figure, specifically her. Thus, in this third step, Isabel Gómez Aranda firsthand learned about Azcona's narrative concerning his own mother or the search for her.

EL PASO TRES se desarrolló mediante una performance de viaje el 28 de enero de 2024. La performance sirvió como cierre de la exposición Abel Azcona. Mis familias 1988-2024 en el Centro de Arte La Panera de Lleida y como primer contacto de la madre biológica de Abel Azcona con la obra del artista, no conociendo a Azcona todavía en persona. En el marco de la exposición meses atrás Abel Azcona había realizado la performance donde se realizó la lectura del resultado de la prueba de ADN, dando sentido invitar a la madre, según el resultado positivo de la muestra clínica, al cierre de la misma. En un viaje de ida y vuelta durante todo el día Isabel Gómez Aranda viajo desde Málaga hasta Lleida y asistió a una visita guiada, al cierre de la muestra, por el equipo del museo. Durante más de una hora la madre pudo interacciones performativamente con las instalaciones de la exposición, leer todos los procesos, visionar las piezas de video y acercarse a la obra de Azcona en torno a la familia. La mayoría de piezas expuestas tenían una relación directa con la figura materna y en concreto con ella misma. Así en este tercer paso Isabel Gómez Aranda conoció de primera mano el relato y la narración de Azcona en torno su propia madre o la búsqueda de la misma.

Ticket for the trip from Malaga to Lleida purchased from Isabel Gómez Aranda.

Billete del viaje de Málaga a Lleida comprado a Isabel Gómez Aranda.

In the third step, for the first time, Isabel Gomez Aranda participated in person and traveled to Lleida to see the exhibition dedicated to her son. As a closing performance of the exhibition, Isabel toured the art center and was the last visitor of the show. / En el tercer paso por primera vez Isabel Gomez Aranda participo de forma presencial y viajó a Lleida a ver la muestra dedicada a su hijo. A modo de performance de clausura de la muestra Isabel recorrió el centro de arte y fue la última visitante de la exposición.

THE FOURTH STEP was activated through ninety handwritten sheets created in collaboration with the first-person testimony as the life story of Isabel Gómez Aranda. For several weeks, Isabel was invited to handwrite her entire life experience, but after several failed attempts, the artist's studio itself assisted her by sending ninety questions formulated by Azcona and the transcription and construction of the narrative transcribed with Isabel Gómez Aranda's answers.

EL CUARTO PASO se activó mediante noventa hojas manuscritas creadas en colaboración con el testimonio en primera persona como relato de vida de Isabel Gómez Aranda. Durante varias semanas se invitó a Isabel a escribir manuscritamente toda su experiencia vital, pero tras varios intentos fallidos el propio estudio del artista la ayudó con el envío de noventa preguntas formuladas por Azcona y la transcripción y construcción del relato transcrito con las respuestas de Isabel Gómez Aranda.

I was born in Valencia on February 20, 1970, in the old hospital in the Pilar neighborhood, and honestly, I don't remember much about my birth. There are times when I don't remember what I ate yesterday, so imagine trying to remember my birth. I was born into a very humble household, from the hospital they took me to a very humble home in the Chinatown neighborhood, and well, that's where I was raised. Without money, because my family didn't have money, but with warmth, with quite a lot of warmth. My mother was a hard worker, a woman who put in a lot of effort for my brother and me.

Valencia for me is my homeland, where I was born and where I spent my childhood, where I went through my first years, until I was twelve or thirteen years old when I left home and left Valencia, but I have returned many times. It is my land. The land where I lived, where I was born, where I shared all my years with my mother and my brother Rafa, my sister Aurora, and my brother Daniel. The land that gave me life, well, the one who gave me life is my mother, but in that land.

You are my only child. I only have one child and that is you. I have no other children. It's not that I don't remember or anything else, it's that after you, I didn't have more children because I wasn't in a position to have many children with the life I was leading and the problems I had; and my mind was really very out of it, to be honest, so I only had you. You were and will be my only child. My only child and then I had my tubes tied and I didn't have any more children because I was leading a very complicated life and I couldn't risk getting pregnant every year, so I had my tubes tied and that was it.

You were not an accident. I got pregnant, although I didn't realize I was pregnant until three or four months in. When I noticed my period didn't come, that's when I realized. I don't consider you an accident, but it also wasn't something I was looking for or expecting. Moreover, my mind was very scattered, and I didn't even know what I wanted at that time. I got pregnant without realizing it, honestly. I don't know how. I slept with many men and clients and did things in a haphazard way; with my mind lost, I ended up

Yo nací en valencia el 20 de febrero de 1970, en el hospital viejo en el barrio del Pilar y no me acuerdo mucho de mi nacimiento la verdad. Hay veces que no me acuerdo de lo que comí ayer, así que imagínate acordarme de mi nacimiento. Nací en una casa muy humilde, del hospital me llevaron a una casa muy humilde en el barrio chino y bueno, allí me crié. Sin dinero, porque mi familia no tenía dinero, pero con calor, con bastante calor. Mi madre era una gran trabajadora, era una mujer que se esforzaba mucho por mi hermano y por mí.

Valencia para mi es mi tierra natal, donde yo he nacido y donde yo he vivido mi infancia, donde he pasado por mis primeros años, hasta los doce o trece años que me fui de casa y me fui de Valencia, pero he vuelto muchas veces. Es mi tierra. Mi tierra donde yo viví, nací, donde compartí con mi madre todos mis años y con mi hermano Rafa, con mi hermana Aurora y con mi hermano Daniel. La tierra que me dio la vida, bueno la que me dio la vida es mi madre, pero en esa tierra.

Tú eres mi único hijo. Yo solo tengo un hijo y eres tú. No tengo ningún hijo más. No es que no lo recuerde u otra cosa, es que después de ti ya no tuve más hijos porque tampoco estaba yo para tener muchos hijos la verdad con la vida que llevaba y los problemas que tenía; y la cabeza la tenía realmente muy ida, la verdad, así que solamente te he tenido a ti. Fuiste y serás mi único hijo. Mi único hijo y después ya me ligaron las trompas y no volví a tener más hijos porque llevaba una vida muy complicada y no podía arriesgarme a quedarme embarazada cada año, entonces me ligué las trompas y se acabó.

No fuiste un accidente. Me quedé embarazada, aunque yo no me enteré de que estaba embarazada hasta los tres o cuatro meses. Cuando vi que no me bajaba la regla entonces ya me dice cuenta. Yo considero que un accidente no fuiste, pero tampoco fue algo que yo buscaba, yo esperaba. Además, yo tenía la cabeza muy ida y no sabía ni lo que quería en ese tiempo. Me quedé embarazada sin darme cuenta, la verdad. No sé cómo. Me acostaba con muchos hombres y clientes y hacía las cosas de aquella manera: la cabeza perdida pues me quedé

pregnant. But well, I don't call it an accident. What is true is that I didn't know I was pregnant.

I don't regret giving birth to you. If I had regretted it, I would have terminated the pregnancy earlier. I carried you for nine months, even a bit longer because I had a prolonged labor. You took a bit more than nine months to come out… Of course, I don’t regret it, and seeing how you turned out now, even less so. But honestly, I wasn't very sure, I was in a really bad state. My mind was in a terrible place, and I didn’t know what I wanted. I was scared of everything and very frightened. Frightened of being a mother, frightened of what was going to happen, what was going to become of me, you name it. Really bad, honestly. I was in a terrible state. I didn’t have any support either. I was just a kid wandering the streets, living however I could, and just the thought of being on the street with a baby… That terrified me. But I don't regret giving birth to you, not at all. I didn’t have my thoughts together. I was quite out of control.

I have only attended my own childbirth in my life. My childbirth is the only one I have witnessed, and honestly, I don't even remember it well, but I haven't attended any others. I really don't remember much from that time.

I realized I was pregnant with you at around four or five months when I noticed my period wasn't coming and my belly started to grow. Sometimes I touched my belly. And you kicked, of course you kicked. The problem was that I was moving from place to place, on the street, adrift. I slept in shelters, in inns that I paid for myself. I was prostituting myself until my belly got quite big. Until I saw that it could harm me, and I stopped, but that's how I made a living, paid for hostels, and ate; then I started begging because I couldn't prostitute myself anymore, I was scared. I was scared of hurting you or myself. So I decided to beg for food and sleep on the street. And all that.

embaraza. Pero bueno, yo no lo llamo un accidente. Lo que sí que yo no sabía que estaba embarazada.

No me arrepiento de haberte parido. Si me hubiera arrepentido lo hubiera perdido antes. Yo te tuve hasta los nueve meses, incluso un poco más porque yo tuve el parto de la burra.Tú tardaste un poco más de nueve meses en salir… Claro que no me he arrepentido, y viendo ahora cómo has salido tú aún menos. Pero bueno, yo no lo tenía muy claro la verdad, yo estaba muy mal. Mi cabeza estaba muy mal y yo no sabía ni lo que quería. Tenía miedo a todo y estaba asustada. Asustada por ser madre, asustada de qué iba a pasar, qué iba a suceder, yo que sé. Muy mal, la verdad. Estaba fatal. No tenía apoyo ninguno tampoco. Era una cría tirada por la calle, de cualquier manera, y solo pensar que iba a estar en la calle con un bebé… Eso me aterrorizaba. Entonces por eso; pero no me arrepiento de haberte parido, no me arrepiento para nada. Tampoco tenía las ideas claras. Estaba bastante descontrolada.

Solo he asistido en mi vida a mi propio parto. Mi parto es el único que yo he visto y la verdad que ni me acuerdo, pero no he asistido a ninguno más. No recuerdo, la verdad que no recuerdo. Yo de esa época recuerdo muy poco, la verdad.

Me di cuenta de que estaba embarazada de ti a los cuatro o cinco meses, cuando me di cuenta que no me bajaba la regla y me empezó a crecer la tripa. A veces si me tocaba la barriga. Y dabas patadas, claro que dabas patadas. El problema es que estaba de aquella manera de un sitio para otro, en la calle, tirada. Dormía en albergues, en pensiones que pagaba yo. Yo me estuve prostituyendo hasta tener ya bastante barriga. Hasta que vi que me podía hacer daño y lo dejé, pero con eso vivía, pagaba hostales y comía; después ya me puse a pedir, me puse a pedir limosna porque ya no podía prostituirme, ya me daba miedo. Me daba miedo hacerte daño a ti o de hacerme daño yo. Entonces decidí ponerme a pedir, a mendigar para comer y a dormir por la calle. Y todo eso.

I met Manuel Lebijo, well if you are thirty-six years old, then thirty-seven years ago (almost thirty-eight). I arrived in Pamplona pregnant for a very short time and met Manuel there in Pamplona. I was prostituting myself in that square by Correos, in that square. Honestly, I don't know what it's called now. I don’t really remember the name… the Plaza del Caballo or something like that. I don't remember very well, but I'm sure I met him in Pamplona. Add a year to your age. I met him when I was newly pregnant, but I don't know the exact year. I'd have to count it on my fingers. You count it, it will be easier for you than for me. Okay?

Since I arrived in Pamplona, I worked there in the square. When I arrived, I started to make a living there in that square. Since my belly was still small, I could still work in prostitution. And then I met Manuel there in the square at night. He passed by there. The first time I saw him in the square, and then I saw him again in a bar. When I finished work, I went to a bar to eat something early in the morning, and he was sitting there in a bar. I don't remember the name of the bar. He surely remembers, but I don’t. And there we made friends, ate something, drank, and got to know each other. And from then on, we stayed together, and he accompanied me to work as a prostitute every day. He was there sitting while I prostituted myself. Until my belly started to grow and I stayed at his mother’s house for a while. But it stressed me out because they didn’t want me to be pregnant there, and they didn’t want us to have relations there in the house or anything; and in the end, feeling stressed, we went to Madrid. That's where you were born, in Madrid. And well, that’s what I remember most. I met him while prostituting myself when I had been in Pamplona for two or three days. In that bar eating early in the morning, there he was; we ate and drank, and from then on, we went out together. And from then until you were born. Then it all ended. Everything ended.

We spent a lot of time living on the street after leaving his mother’s house, of course, a while there in Pamplona and then we decided to go to Madrid. And there in Madrid, we were also on the street. We went to social services, and they gave us a room in a boarding house. We stayed in the boarding house until I gave birth; and well, then I gave birth, you stayed in the hospital, and I left. And that's it, not much more.

A Manuel Lebijo le conocí, pues si tú tienes treinta y seis años, pues hace treinta y siete años (casi treinta y ocho). Llegué a Pamplona embarazada de muy poco tiempo y conocí a Manuel allí en Pamplona. Yo me estaba prostituyendo en la plaza esa de Correos, en esa plaza. La verdad que no sé cómo se llama ahora. No me acuerdo bien del nombre… la plaza del Caballo o algo así. No me acuerdo muy bien, pero seguro que en Pamplona lo conocí. Ponle un año más de los que tú tienes. Lo conocí embarazada de poco tiempo, pero el año exactamente no lo sé. Tendría que contarlo con los dedos. Cuéntalo tú, que te será más fácil que a mí. ¿Vale?

Desde que llegué a Pamplona, yo trabajaba allí en la plaza. Yo cuando llegué empecé a buscarme la vida allí en esa plaza. Como tenía poquita barriga todavía podía trabajar en la prostitución. Y entonces yo conocí a Manuel allí en laplaza, por la noche. Él pasaba por allí. La primera vez lo vi en la plaza y luego lo volví a ver en un bar. Cuando yo terminé de trabajar, me fui a un bar a comer algo de madrugada y él estaba allí sentado en un bar. No me acuerdo del nombre del bar. Él seguro que se acuerda, pero yo no me acuerdo. Y allí ya establecimos amistad, comimos algo y bebimos y nos conocimos. Y desde entonces, pues ya nos juntamos y él me acompañaba a prostituirme todos los días. Él estaba por allí sentado y yo me prostituía. Hasta que empezó a crecerme la barriga y yo estuve en la casa de su madre un tiempo. Pero me agobiaba porque ellos no querían que estuviera embarazada allí y no querían que tuviéramos relaciones allí en la casa ni nada; y al final agobiados nos fuimos para Madrid. Allí fue donde naciste tú, en Madrid. Y bueno, y yo me acuerdo sobre todo de eso. Yo lo conocí a él prostituyéndome cuando llevaba yo dos o tres días allí en Pamplona. En el bar ese comiendo de madrugada, allí estaba él; comimos y bebimos y a partir de allí salimos juntos. Y desde entonces hasta que tú naciste. Luego ya se acabó. Se acabó todo.

Estuvimos mucho tiempo en la calle viviendo tras irnos de la casa de la madre, claro, un tiempo allí en Pamplona y luego ya decidimos irnos a Madrid. Y allí en Madrid estuvimos también en la calle. Fuimos a la asistencia social y nos dieron una pensión. Estuvimos un tiempo en la pensión hasta que di a luz; y bueno, luego ya di a luz, tú te quedaste en el hospital y yo me fui. Y ya está, y poco más.

For me, prostitution is something that I, being a minor, agreed to do to make a living and it is a means of getting money, but today it is something very far away in my life. Prostitution has not been in my life for many years. I was a prostitute until shortly before my belly grew and when it grew, I didn't prostitute myself anymore and I started begging (asking for money on the streets). The rest of the time I was on the street I was begging. I almost never went into prostitution again because the truth is I was very chastened by prostitution. I had a very bad time with prostitution, I had very bad things in prostitution. They tried to rape me, they hit me, they did atrocious things to me, so I was very chastened and I have never become a prostitute again. It's something that is there, that has stayed there, even though it has been out of my life for a long time, many years. And I hope I never have to resort to it because it is something that marked me for life: prostitution. Something that marked me and left its mark on me and now I am forgotten there and the less I remember the better.

In prostitution between the clients and your father I found everything, better people, more bad people, very dirty, very rude, very dirty, very harsh, some did not want to pay you, others raped you, others hit you... There was everything. . There was everything in prostitution. I have gone through very bad things in prostitution, but bad bad things.

I'm not clear at all and I don't know who your biological father is, Abel, I'm not at all clear. One of my clients, I don't know if the businessman or one of them, the truth is that I'm not clear about it nor do I remember it either, but Manuel certainly not because I met Manuel pregnant. And I was short on time, plus I was short on time. So Manuel discard it. And your biological father, the truth is one of them, but I don't remember the truth.

Para mí la prostitución es algo en lo que yo, siendo menor, pues accedía para buscarme la vida y es un medio de conseguir dinero, pero hoy en día es algo ya muy lejano en mi vida. Hace muchos años que no está en mi vida la prostitución. Yo me prostituí hasta poco antes de que me creciera la barriga y cuando ya me creció, pues no me prostituí más y ya pedía (pedía dinero por las calles). Ya todo el resto del tiempo que estuve en la calle fue pidiendo. Ya casi no me volví a prostituir porque la verdad quedé muy escarmentada de la prostitución. Lo pasé muy mal con la prostitución, pasé cosas muy malas dentro de la prostitución. Me intentaron violar, me pegaron, me hicieron barbaridades, entonces quedé muy escarmentada y no me he vuelto a prostituir nunca más. Es algo que está ahí, que se ha quedado ahí, aunque esté fuera de mi vida ya hace mucho tiempo, hace muchísimos años. Y espero no tener nunca que recurrir porque es algo que me marcó para toda la vida: la prostitución. Algo que me marcó y dejo huella en mí y ya pues ahí quedo en el olvido y cuanto menos me acuerde mejor.

En la prostitución entre los clientes y tu padre me encontré de todo, mejores personas, más malas personas, muy cochinos, muy maleducados, muy guarros, muy duros, algunos no te querían pagar, otros te violaban, otros te pegaban… Había de todo. En la prostitución había de todo. Yo he pasado cosas muy malas en la prostitución, pero malas malas.

No tengo nada claro ni sé quién tu padre biológico, Abel, no lo tengo nada claro. Uno de mis clientes, no sé si el empresario o uno de ellos, la verdad que no lo tengo claro ni me acuerdo tampoco, pero Manuel seguro que no porque yo a Manuel lo conocí embarazada. Y de poco tiempo, además yo estaba de poco tiempo. O sea que Manuel descártalo. Y tu padre biológico, la verdad es uno de ellos, pero no recuerdo la verdad.

With one of the clients, I spent two or three days, but I have no contact with him. The thing is, I don’t remember, I don’t remember very well, because they were just men passing through, just for a moment and then gone... so the truth is I didn’t have much of a relationship with them. Therefore, I’m not clear about any of it. I can’t tell you anything about your biological father because, as I said, I don’t even know who he is, nor do I know anything about him. No matter how much I think about it, I don’t know, I don’t remember anything, nor can I even imagine what he’s like or what he would be like, I don’t know. I don’t know who he is or what he might be like. I met many, many men. Even if I had an idea, I didn’t know any of them for a long time. They were all transient. In prostitution, you don’t have many regular relationships; it’s something quick and disgusting, besides. There’s nothing good about it.

I don’t know if I would say that a relationship in prostitution is like a rape with money involved, but in some ways, yes. I don’t know. Rape is harsher, and if they physically hurt you more; if they beat you or hurt you or force you, it’s harsher, but prostitution is just very disgusting… because you’re touched by hands you don’t want, you do things you don’t feel like doing, and only for money, of course. Because money is involved. But anyway, both things are disgusting. Disgusting and painful, both rape and prostitution. They could go together, yes. Prostitution is very hard and so is rape. Because in prostitution I have been raped; besides being prostituted, I have been raped and not paid and hurt. So, yes, I do consider prostitution like rape. Especially in a case like that. And usually, it’s just a lot of disgust. A lot of contempt, a lot of disgust.

I don’t know if your father abused me or not. He was a client who paid for my services and I provided them. I’m sure I felt a lot of disgust because it’s the only thing I felt with all of them, disgust. And yes, if that’s called abuse, then he abused me because I felt tremendous disgust being abused, being touched, being drooled on, and many were so unpleasant, really difficult moments, and I was just a girl on top of that. Imagine that.

Con uno de los clientes estuve dos o tres días, pero no tengo contacto. Es que no me acuerdo, no me acuerdo muy bien, porque como eran hombres de nada, de pasar el rato y fuera… pues la verdad que no tenía mucha relación con ellos. Entonces, no lo tengo nada claro. No te puedo contar nada de tu padre biológico porque como te digo no sé ni quien es, ni sé nada de él. Por mucho que lo piense no lo sé, no recuerdo nada, ni imagino tampoco cómo es o como sería, no lo sé. Ni sé quién es ni sé cómo puede ser. Conocí muchos, muchos conocí. Aunque me hiciera una idea, así de mucho tiempo no conocí a ninguno. Eran todos pasajeros. En la prostitución no tienes muchas relaciones asiduas, es algo rápido y asqueroso, además. No hay nada bueno.

No sé si afirmar que una relación de prostitución es como una violación con dinero de por medio, pero de alguna manera sí. No lo sé. La violación es más dura, y si te hacen daño físicamente más; si te golpean o hacen daño o te lo hacen a la fuerza es más duro, pero la prostitución lo que da es mucho asco… porque te tocan unas manos que no deseas, haces cosas que no te apetecen y solo por dinero, claro. Porque el dinero está en medio. Pero bueno, las dos cosas son un asco. Un asco y doloroso, tanto la violación como la prostitución. Podrían ir juntas, sí. Es dura, la prostitución es muy dura y la violación también. Es que a mí en la prostitución me han violado; encima de que me estaban prostituyendo, me han violado y no me han pagado y me han hecho daño. Así que sí que considero la prostitución como una violación. Sobre todo, en un caso así. Y de normal, mucho asco. Mucho desprecio, mucho asco.

Tu padre no sé si abuso de mi o no. Fue un cliente que pago mis servicios y yo pues se los di. Seguro que mucho asco sentí porque es lo único que sentía con todos, asco. Y sí, si eso se llama abusar, pues me abusó porque yo sentía un asco tremendo que me abusaran, que me tocaran, que me babearan y muchos eran tan desagradables, de verdad, momentos muy difíciles y yo encima era una niña. Imagínate.

I don't think there's any possible way for you to ever meet your biological father because I don't know him myself. If I don't even know him, it's impossible for you to know him. Impossible, because I’m not even sure who he is, and I don't remember half of the men I was with either. I don't remember who I was with at that time, I met some, but no way. I couldn’t tell you who it was. Not because I didn’t have a relationship with them, it was mostly just sex. Disgusting, besides.

I know Manuel told you that I was involved with a businessman from the Valencian nightlife. He was just another client; and I wasn't involved with him, I spent the same amount of time with him as with everyone else, and I don’t know where Manuel got the idea that I was involved with him. Yes, he could be your father, but I don’t know where he is, who he is, or where he lives, and I know nothing about him. I don’t know where Manuel got that information. He was just another client like any other. Understand? So, he was just another man, I don’t know where he lives, I don’t remember who he was, and I don’t know anything about him, honestly, I can help you very little there.

Describing Manuel Lebrijo, I’d say he’s more short than tall, he's thin (and now even thinner, he used to be a bit chubbier). He has brown hair, although when I met him it was lighter brown (now it’s a bit darker). I think he had brown eyes, but I don’t remember much about his face, honestly. I was out of it. But anyway…

Manuel came from Badajoz. He was born in Badajoz, according to what he told me; and yes, not before, but the last time I talked to him, which was right before contacting you, he mentioned that he had, that he had a daughter with Arantza and her sisters. I met his sisters because when I was pregnant with him, I stayed at his house for a few days, with his sisters and his mother. I didn't meet the father because he wasn’t living anymore, but I did meet the sisters and the mother. At that time, they were alive, and I met them.

As soon as I recovered, I left the hospital. When I recovered from childbirth, I think...